BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Adam Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, described it as “sort of an unmonumental monument.”

Indeed, in some ways, it’s the opposite of Barry Diller’s glittering, high-profile, heavily programmed Pier55 project that sank last month in the face of repeated lawsuits by waterfront activists.

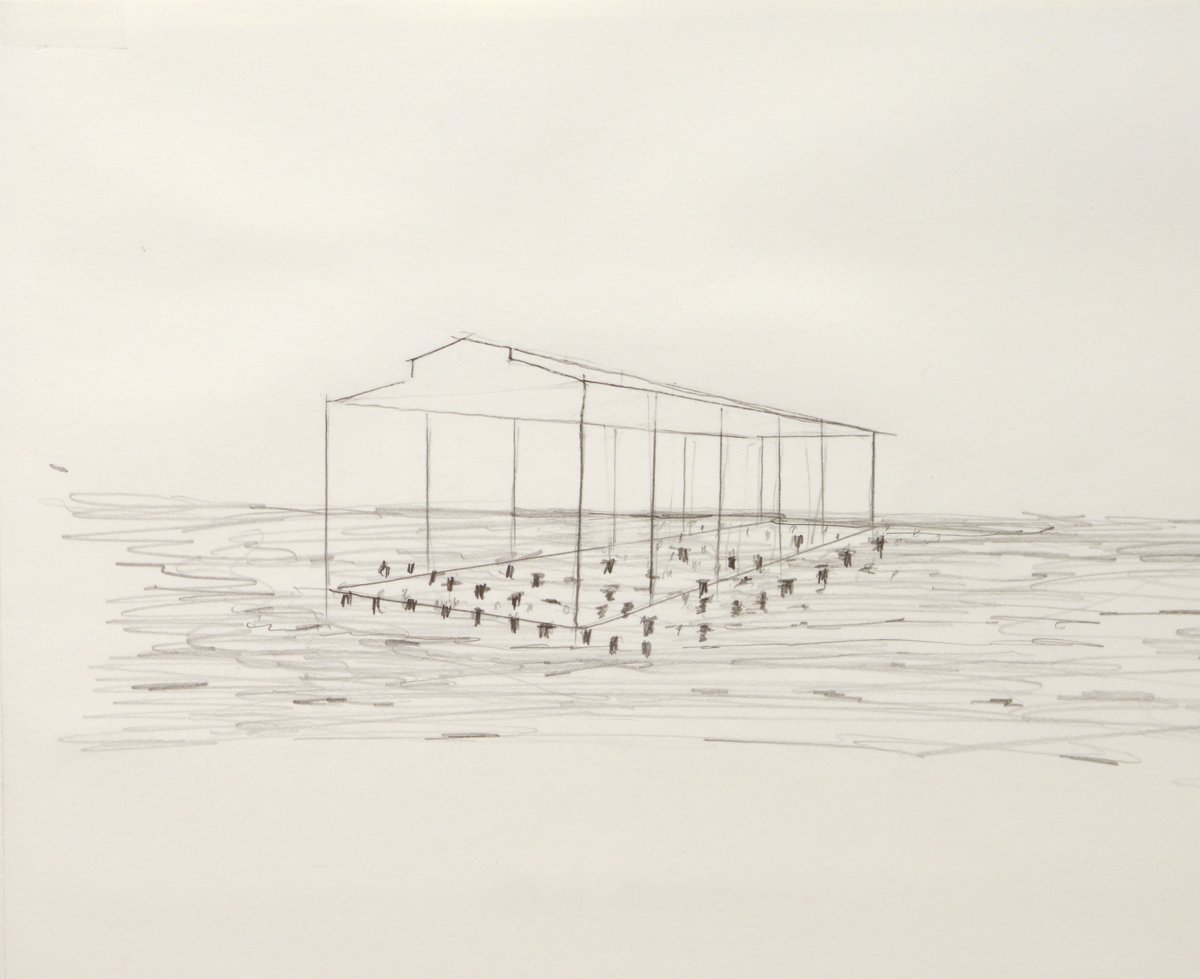

Last week, the Whitney released design renderings of “Day’s End,” a planned public artwork by David Hammons that would sit off the southern edge of Gansevoort Peninsula, opposite the new museum.

The work would be made up of round steel beams that would outline the exact shape of the former pier shed on Pier 52, which once abutted the peninsula’s southern edge.

In its first public unveiling, Weinberg presented the plan to the Parks and Waterfront Committee of Community Board 2 on the evening of Wed., Oct. 4. The day before, Weinberg, in a telephone interview, laid out the plan to The Villager.

He noted that Hammons — who is African-American and has lived in New York City for more than four decades — is considered among the most important artists working in the U.S. today. He is known for his often provocative — yet also extremely poetic — pieces that are “formally beautiful,” Weinberg noted.

“And he’s an artist who really thinks about the context his works will appear in,” he added.

“He came to the museum when it was under construction, looked out the window and saw Gansevoort,” Weinberg recalled, referring to the wide west-facing window in the Whitney’s largest gallery space.

Hammons, 74, remembered how the original Pier 52 pier shed had once sat off the southern side of Gansevoort, and how, in 1975, artist Gordon Matta-Clark had cut five openings in the side of the disused structure.

“He sent us a drawing, totally unsolicited,” Weinberg said of Hammons, “the idea of creating a skeletal ghost remnant of this torn-down warehouse. He made the proposal and we were really interested by it. I think it’s a quite magical piece.”

At a time when battles are literally raging around the country over the tearing down of historic monuments — like statues of Confederate soldiers and Christopher Columbus — Weinberg noted that this proposed testament to the past is completely apolitical.

Hammons’s proposal called for a perfectly accurate framework of the former pier shed at full scale.

“The warehouse itself was larger than the Whitney Museum,” Weinberg noted of the old pier shed.

Hammons’s exacting design calls for the piece to be 373 feet long by 75 wide by 50 feet high — with a clerestory running along the middle of the structure’s top — to mimic the precise dimensions of the original structure.

“David Hammons really wanted it to be the exact spot, the exact size,” Weinberg noted.

The beams and poles would be made out of 8-inch-diameter brushed steel, which would not be shiny, Weinberg said.

The artist did not want every single original beam recreated, but rather to capture the overall shape of what had once stood there.

“That was one of the original questions,” Weinberg recalled, as to how much of the former pier shed Hammons wanted to recreate. “It’s the essential form, the outline.”

Unlike Pier55, which — raised high on its extra-tall pilings and with its undulating landscape — would have been impossible to miss, “Day’s End” won’t always be so apparent to the eye.

“Depending on the weather, it would be more present,” Weinberg noted. “Sometimes it would disappear in the clouds and fog.”

The public artwork would not be merely temporary, but there for the long term.

“It would be kind of a permanent reference — as long as it could stand,” the museum director said.

Unlike Pier 55 — with its dense network of support piles — “Day’s End” wouldn’t prevent boaters and kayakers from using that spot in the river.

“It would not change any of the uses of the park,” Weinberg said, “because it would just sort of be there.”

In short, kayakers would be able to launch their boats at the spot and paddle right through the ethereal structure.

The Whitney has spent the last year and a half doing an engineering study for the project. But Weinberg stressed that the museum’s leadership felt it was very important to go to the community first before putting the plan out there. That was blown, however, when the Times, a few weeks ago, spilled the beans and published an article about the plan.

“The Barry Diller project fell through and somebody leaked the project to the New York Times,” Weinberg said. “That really upset me.”

He said he called the reporter who wrote the story and told her, “It’s pretty crappy that they would publish it before the Community Board 2 meeting. Basically, the Times told me that they wouldn’t and couldn’t hold it.”

Like Diller on Pier55, the Whitney had been working with the Hudson River Park Trust on the “Day’s End” project. In fact, the Whitney would not own the Hammons piece; it would be owned by the Trust — the state-city authority that operates the 5-mile-long West Side waterfront park — since it would be in the Trust’s jurisdiction.

“They are very supportive of it,” Weinberg said of the Trust’s view of “Day’s End.”

Although he said he could not give an exact price for the project, the director said, “It’s much more than a million dollars. You have to anchor it,” he explained.

Poles on the structure’s northern side would sit on the peninsula’s edge, while the poles on its southern side would have to be installed in the riverbed. The process of obtaining permits, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the state Department of Environmental Conservation, also costs money.

The Whitney would finance the project and its construction. Weinberg said they would “like to see it happen in two to three years, if possible,” and that building the artwork and installing it would take less than nine months.

Before anything, though, the Whitney wants there to be local buy-in for the scheme.

“If the community is enthusiastic, the next step is to go out and fundraise,” Weinberg said.

Having carefully watched the Pier55 process and its failure, the Whitney is being careful not to repeat any of its mistakes.

“One thing I can say is there will be no poured concrete into the water,” Weinberg stated.

He was referring to the Achilles heel of the Pier55 project — namely, the requirement under the federal Clean Water Act that because the pier’s special “pot” piles were to have been filled on-site with pourable concrete during the actual construction process, the pier and its uses had to be “water-dependent.” Back in March, in a stunning decision, a federal judge ruled there was no reason why the “entertainment pier” had to be built in the river as opposed to on land, and she promptly rescinded its Army Corps permit, leaving the project dead in the water.

Asked his thoughts about the demise of “Diller Island,” Weinberg was carefully what he said about that aquatic hot potato.

“The intent was to try to do a good thing,” he offered. “Our is a different kind of project. It’s an artist-driven project. It’s an homage.”

Specifically, the artwork is a tribute to the 19th- and 20th-century working waterfront and its built fabric.

“Especially now that they’ve taken down the pier sheds, and they’re taking down the Gansevoort building,” Weinberg noted. He was referring to the Department of Sanitation’s former incinerator-turned-garage on the peninsula, which eventually will be redeveloped as parkland as part of Hudson River Park.

The spectral steel arch that stands at the foot of the former Pier 54, at W. 13th St., is a remnant of the former pier where the Carpathia brought the Titanic’s survivors.

“In fact, I’m looking at it right now through my window,” Weinberg noted. “We know that the arch connected to a whole pier shed that’s no longer there.”

The Whitney would create a free mobile Web site (not an app since it would not have to be downloaded in order to use), allowing people to learn the area’s rich history simply by pointing their phones at certain locations.

“So you can hold up your Android or your iPhone and see the whole history of the waterfront,” Weinberg explained.

“There would even be images of the first Native American settlement there — it would be approximate,” Weinberg said. “Herman Melville working on Gansevoort as a customs inspector. Alexander Hamilton brought back across the river and presumably died on Horatio St.…‘gay beaches,’” he said, referring to the cruising scene on the former dilapidated piers that have been replaced by Hudson River Park.

The program would also detail the area’s past and current arts scene.

“Artists,” he said. “There are over 300 artists currently at Westbeth. Everybody thinks all the artists have moved to Bushwick, but they’re still in the Village.”

Engaging with the community is clearly important for the Whitney on this project, about which a documentary would also be made. An oral history of the area, including “longtime neighbors, artists, merchants, community activists and cultural leaders,” will also be done.

Tom Fox, one of the plaintiffs in the City Club of New York lawsuits against Pier55, said the Whitney was “doing things the right way,” by ensuring it first got neighborhood support and by putting all its cards on the table at the outset.

Told of that, Weinberg said, “I’m happy that they feel that way.”

Madelyn Wils, the president and C.E.O. of the Trust, was at last Wednesday’s presentation.

“We think ‘Day’s End’ is an inspiring idea that celebrates the history of the Hudson River waterfront,” she said. “We look forward to hearing the community’s thoughts, and, should the project move forward, to working with the Whitney to make this a vibrant addition to Hudson River Park.”

Susanna Aaron, vice chairperson of the C.B. 2 Parks and Waterfront Committee, said its reaction was unanimous in support of the project. She noted that some questions from the audience included how the structure would affect the peninsula and whether oysters would be allowed to grow on it.

Aaron noted that, as Weinberg explained during his presentation, there would be 65 feet between each “anchor,” or vertical pole supporting the structure, and only 12 anchors in total, so the artwork would be very open, allowing boating and other activities in the waters it straddles.

One of the anchors would be built in such a way as to allow access to the Spectra natural-gas pipeline that runs under Gansevoort, Weinberg noted.

The development of a park on Gansevoort itself is not happening soon, according to Aaron.

“We’re years away from scoping that park,” she said.

Aaron also noted that Wils assured the Hammons plan would go through all necessary environmental reviews.

About 80 people attended the meeting.

“We really appreciate being engaged super-early,” Aaron added of the Whitney’s community outreach.

Sharon Woolums, a public member of the Parks and Waterfront Committee, was somewhat neutral on the whole affair. Woolums’s talking point in The Villager last week criticizing another prominent public artwork — Ai Weiwei’s “Good Fences Makes Good Neighbors” cage installation underneath the Washington Square Arch — has been garnering international media attention.

“I like it,” she said of “Day’s End.” “I mean, I went to those piers. I could do without it, too. I kind of like it as a nod to the past — it looks like a ghost. And if they want to go to all that expense to give a nod to the past, fine.”