BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Updated Wed., Nov. 29, 11 p.m.: Pier 40 — the Hudson River Park’s largest pier — must be developed with sensitivity to the surrounding community, meaning all of the hulking structure’s available development space should not be utilized, yet more sports fields should be added, according to a new draft report by a Community Board 2 working group.

The report also notes that, in an effort to maximize the sprawling W. Houston St. pier’s revenue-generating potential, the park’s governing agency is seeking to develop it with a massive megaproject that could cost upwards of $850 million.

The Future of Pier 40 Working Group released its draft report on Nov. 17. This report will get a final review at the Nov. 30 meeting of the working group, which will then craft an advisory resolution and vote on it.

(The group’s Nov. 30 meeting is open to the public, but will be an “executive session,” meaning members of the public will not be allowed to comment or ask questions.)

The full board of C.B. 2, in turn, will vote on the resolution, likely in mid-to-late December.

Rather than a traditional resolution, featuring suggested actions, the recently released draft report has 21 “findings.” Tobi Bergman, the working group’s chairperson, described it as “more guidance than prescription.”

Specifically, the working group was formed “to help establish parameters for potential redevelopment proposals that provide a stable source of income to support [Hudson River Park] operations while protecting the park from harmful impacts and increasing space for recreation… .”

E-survey in mix

In addition, over this past summer, the working group sent out an e-mail survey seeking people’s input on the future of Pier 40. A total of 3,140 people responded. All three community boards — Community Boards 1, 2 and 4 — that border the 4.5-mile-long park sent the survey to their e-mail lists, as did local politicians whose districts include the park, plus the three local youth-sports leagues — Greenwich Village Little League, Downtown United Soccer Club and Downtown Soccer League — the Manhattan Youth organization and the Village Community Boathouse, among others.

(For charts showing the survey’s results click here.)

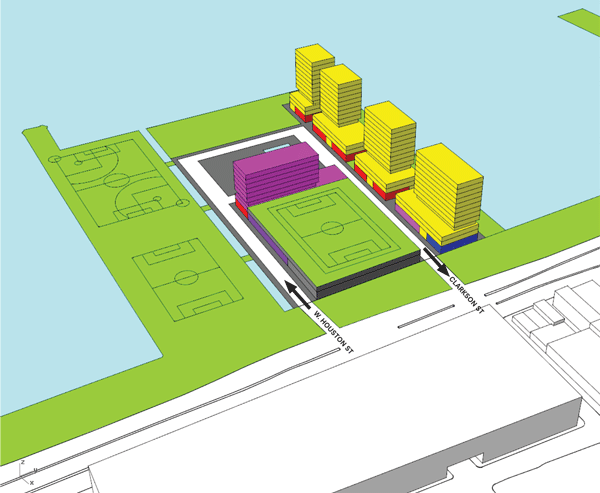

The eight-page draft report notes that Pier 40 is almost 15.5 acres big, “or more than one-and-one-half times the size of Washington Square Park.”

A two-story concrete pier shed covers the whole site except for a center courtyard of roughly 4.5 acres, currently used as sports fields, and a 20-foot wide perimeter walkway.

‘Opportunity for space’

“The pier, by far the largest in Hudson River Park, offers a unique and irreplaceable opportunity for new public open space,” the report notes, “including large-footprint ball fields that are difficult to site elsewhere within the narrow park. The ‘courtyard’ field alone is almost 10 times as big as the only other unpaved sports field in Community Board 2, James J. Walker Park.”

Revenue generator

The Hudson River Park Act of 1998, the park’s founding legislation, states that, “to the extent practicable,” the cost of the park’s maintenance and operation should be funded by limited commercial uses in the park. Regarding Pier 40, the act mandates that the equivalent of at least 50 percent of its footprint must be used for recreational purposes, and that the rest of the pier can be developed commercially, though only with certain types of uses. Throughout the whole park, the act prohibits amusement parks, riverboat gambling, residential housing and commercial offices — and at Pier 40, specifically, the act allows only water-dependent uses, entertainment and commercial recreation.

Since the park’s creation nearly 20 years ago, Pier 40 has provided between 25 percent and 40 percent of the whole park’s annual expenses, most of that coming from the W. Houston St. pier’s long-term car parking. The Lower West Side pier’s other current commercial uses include party boats and a trapeze school.

Past failed efforts

“Two efforts to redevelop the pier ended in failure,” the working group’s report notes, “largely because the community objected to the character and intensity of proposed commercial uses, which were primarily big-box retail and a vast entertainment complex. There were also strong objections to [the proposed] relegation of recreational open space to the rooftops of commercial buildings dominating the site.

“Among factors driving the size and intensity of proposed development [plans for Pier 40],” the report notes, “has been the high cost of repairing thousands of steel piles that support the structure.”

Air-rights dollars

However, the draft report states, redevelopment schemes for the pier, theoretically, need not be so ambitious anymore, after the park act was amended in 2013 to allow the Hudson River Park Trust — the park’s state-city governing authority — to sell the park’s unused development rights to construction sites across the highway.

“The Hudson River Park Trust now has funds available to repair the piles, mostly obtained from the sale of development rights,” the C.B. 2 group’s report notes. “Support for the use of park air rights in the adjacent area was based on the expectation that these funds would reduce the burden of development at Pier 40.”

Indeed, C.B. 2 and Councilmember Corey Johnson, among others, supported the redevelopment of the St. John’s Center site, just east of Pier 40, with a massive project of 1,600 residential units — including the sale of 200,000 square feet of air rights from Pier 40 to that project’s developers for $100 million.

Trust target: $12.5M

The working group’s draft report notes the Trust hopes to continue getting 25 percent of the whole park’s expense budget from revenue from Pier 40, “which would eventually require increasing [annual] net revenue from a Pier 40 development project to $12.5 million.” That’s about double the amount of revenue that the pier currently provides for the park.

In the working group’s view, though, the park authority should probably scale back its plans at Pier 4o, in terms of the amount of revenue it wants to generate there.

A presentation was made to the working group by a Manhattan developer who volunteered to show how a developer would think about the costs of redeveloping the pier.

“That hypothetical showed that it may take a $1 billion project to achieve net income of $12.5 million,” the group’s draft report notes, “suggesting a level of commercial use that may not be feasible given potential community opposition to a project of this scale, especially in the context of concerns expressed by some about the advisability of building grand projects on piers as waters rise.”

In fact, the figure the developer cited for the hypothetical Pier 40 project was $850 million.

Impact and heights

Previous requests for proposals, or R.F.P.’s, for Pier 40 resulted in proposals with allowable uses — such as retail and entertainment — but were opposed by the community for being too “high impact” on the pier and surrounding area. As a result, believing it would be a more low-impact use, the Trust is now pushing to amend the park act to allow commercial offices at Pier 40, the report notes.

“But commercial offices were excluded as incompatible in the [original] act because of concern about tall buildings and privatization of use,” the report says. “Those concerns remain. …”

Eighty-one percent of respondents to the working group’s e-survey said they were concerned about allowing tall buildings in the park. Forty-two percent said more open space at Pier 40 was essential or very important to them, even if it meant having taller buildings there. But 35 percent said it was essential or very important to them not to increase building heights in the park. Forty-three percent of survey respondents oppose allowing commercial office development at Pier 40 (although, due to another 2013 amendment to the park act, Google will have offices at Pier 57 in Chelsea).

Longer leases

According to the working group, the Trust also will be pushing to extend the length of the allowable lease at Pier 40, which would also require an amendment to the park legislation. Currently, leases at the W. Houston St. pier are limited to 30-year terms.

The Trust is reportedly arguing that that length is “insufficient to support the required investment for office development,” and so the authority hopes to increase the lease lengths there up to 99 years.

However, the working group warned that longer leases would increase the “possessory interest” of a developer over the pier while also possibly encouraging larger projects, since they would “enable higher levels of financing.”

In short, according to the draft report, “The [e-mailed] survey showed a continued high level of public concern about privatization.”

The draft report lays out, not necessarily in order of importance, 21 “findings” about the future of Pier 40.

‘Put park first’

First, it states that any R.F.P. that the Trust issues for the pier “must start with recognition that the income generation is secondary to protection and enhancement of park uses, as mandated in the park act.”

Also, any change to the Hudson River Park Act to allow for commercial office use at Pier 40 “would need to be balanced by changes that maximize public open space and assure its public control.” In other words, “Areas of commercial use must be strictly defined to protect the park use and character from privatization,” the report states.

‘Don’t max out’

In a key point, the group’s draft report urges that not all of the pier’s existing unused development rights be used. Factoring in the 100,000 square feet of air rights that will be transferred to the St. John’s project, Pier 40 still has an additional 380,000 square feet of unused air rights left. As for the currently “used” air rights on the pier, its existing three-story “donut”-shaped pier-shed structure encloses roughly 760,000 square feet of space.

“While some commercial office use may be compatible with the goals of the park,” the C.B. 2 working group report states, “full use of the currently available development rights [at Pier 40] may not be ‘practicable’ because of incompatibility of the intensity of the use or the scale of required buildings. …[T]here is no law or regulation suggesting that the Trust will have full access to floor area currently allowed by zoning. … [T]he Trust should anticipate the likely need to reduce the total amount of commercial use in a park setting to win public support for zoning changes.”

Ensure safe access

The working group also feels that, if commercial uses are increased on Pier 40, a separate entrance for the increased commercial traffic must be created to keep pedestrians safe.

“Safe access to and use of the park is more important than revenue from commercial use,” their report stresses.

The report also notes that any future building at Pier 40 should be sited to protect the park and river from shadow impacts and, as required by the park act, provide view corridors from cross streets to the river. Currently, Pier 40 — like Chelsea Piers — does not provide any river view corridors, since its pier shed rings the whole structure.

Add more fields

The draft report also advocates that even more space for playing fields be created at the W. Houston St. “sports pier,” noting the fields are used mostly by neighborhood families, schools and leagues.

“The large size of Pier 40 offers a unique opportunity to increase the amount of space for sports fields serving all the large and growing communities adjacent to Hudson River Park,” the report states. “Substantially increasing space for fields is essential for the growing number of families with children in these neighborhoods and for nearby schools that lack sufficient sports facilities. If the [pier’s] current building is not retained, any redevelopment at Pier 40 should include substantial increase to the number of fields and also add opportunities for indoor recreation to respond to the growing unmet need for youth sports facilities.”

The working group notes that more space for sports fields could also be identified further north in the park.

“Gansevoort Peninsula [between Little W. 12th and Gansevoort Sts.] will be primarily for passive uses, but could still include fields for younger children,” the report adds. “Pier 76 [at W. 36th St.] may be another opportunity to build fields within the park.”

Dog runs, too

The report further recommends that Pier 40 “should support a mix of park uses,” including passive use, with river views, playgrounds, dog runs and more.

But it stresses, “Because ball fields are too large to be located elsewhere and the boathouse depends on access to the protected cove created by the pier, these uses should be prioritized at Pier 40.”

Preserve parking

In addition, monthly and hourly parking should be preserved at the Lower West Side pier, and parking has a strong constituency, the group says.

“Because it has low value per square foot, parking consumes lots of space, but it is a relatively passive use, and its elimination may be disruptive and may generate opposition to a [development] proposal, and therefore needs to be carefully considered,” the report notes.

Putting recreational and sports uses on the rooftop of a new development at Pier 40 needs careful consideration, due to the strong winds on the Hudson River; and measures to mitigate the wind would be needed, the report says. On the other hand, the rooftop would be a good spot to add indoor sports uses, the group says. (Currently, the pier’s main sports-field area is protected from the river’s strong winds since it is ringed by the pier-shed “doughnut.”)

Efforts also should be made so that what would likely be a years-long development project at Pier 40 does not significantly impact use of its sports fields or the boathouse, the report adds, noting that youth sports are an essential part of the area’s “quality of life.”

Height anxiety

As for potentially increasing the height of structures at Pier 40, the report cautions, “Taller buildings at Pier 40 will change the character of the Hudson River waterfront and may cast too many shadows on the park and the river. There are currently no buildings exceeding two stories on the west side of Route 9A [West Side Highway] north of Chambers St. … There is a long and consistent history of objection to extending the Manhattan height context to the river.”

The report notes that, “paradoxically,” 73 percent of survey respondents want more open space [for recreational uses] at Pier 40, even if it results in taller buildings, while 62 percent of respondents think buildings should stay at the current height, even if it means no new open spaces.

“In any case,” the report continues, “the determinant of building height should be based on the overall impact on the park and adjacent neighborhoods, not solely commercial considerations.

“The response of neighbors to taller buildings is impossible to know outside the context of a specific proposal, but any increase to building heights will require a proposal with a high degree of sensitivity to the overall needs and concerns of the entire community.”

R.F.P. next year

As for a “specific proposal” for Pier 40, the Trust won’t issue an R.F.P. until it knows how its effort to amend the park act in Albany turns out. The state Legislature doesn’t go back into session until January, so nothing will happen until after then. According to a source, the Trust would, thus, likely issue an R.F.P. sometime between February and June.

Finally, speaking of wind on the Hudson, and Mother Nature, in general, the C.B. 2 working group’s draft report also says the design of Pier 40 “should prioritize green architecture and flood resiliency and if possible use wind and sun to generate power. One way to build green is to reuse,” the report notes, “so the Trust should not discourage proposals that retain parts of the existing [two-story pier-shed] structure while removing [other] parts to create openness to the river.”