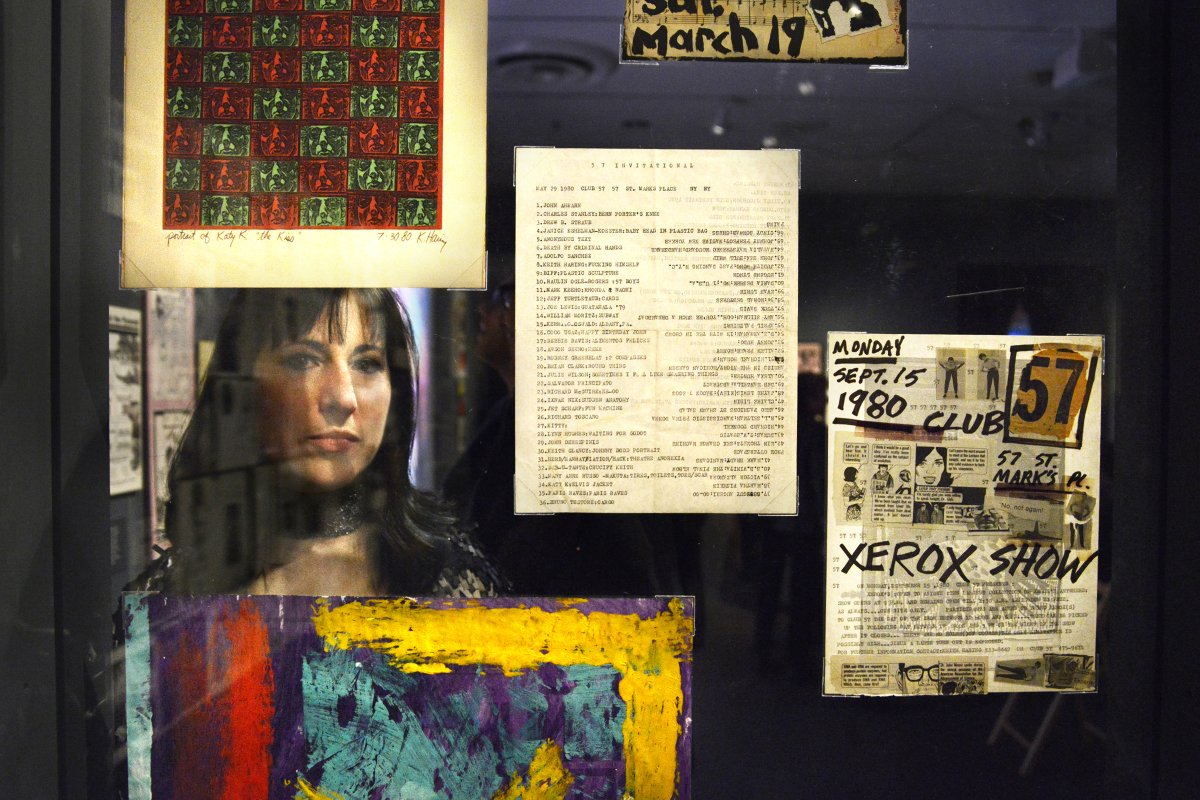

BY BOB KRASNER | “I feel like I’m in a club in the ’80s!” exclaimed celebrity portraitist and street photographer Henny Garfunkel.

Actually, she was at the Museum of Modern Art for the opening of the new exhibit “Club 57: Film, Performance and Art in the East Village, 1978 – 1983,” surrounded by veterans of the scene.

An unabashed homage to the 1980s East Village art scene, the show is appropriately located in the museum’s lower level, as Club 57 was in the basement of a Polish church at 57 St. Mark’s Place. Not just another venue, 57 was the Big Bang of the Downtown art scene.

“Club 57 was such a breeding ground for future major artists, theater folk, photographers, stylish drug addicts and lunatic punk-rock royalty,” said filmmaker John Waters.

Founded and managed by Stanley Strychacki, the alchohol-free venue had a simple but heartfelt credo.

“It was the home of friendship and art,” Strychacki explained. “Without friendship, there won’t be anything.”

“And we’ve all been friends since then,” concurred musician and club veteran Deb O’Nair.

Musician Miriam Linna was there at the beginning, when it was a rock-and-roll venue. In April 1978, she was the drummer for the Zantees, one of the first bands ever to play Club 57, an experience she remembers fondly.

“Stanley was more like a wonderful uncle than a club manager’” she recalled. “He would make us sandwiches after the show. It was great — more of a clubhouse than a club.”

After about a year, “the art crowd came in and took it to another level,” Linna said. Former Sonic Youth guitarist Lee Ranaldo, an aspiring painter at the time (“I still am,” he admitted), loved the whole scene.

“There was stuff going on there that wasn’t going on anywhere else’” he remembered. “The Mudd Club was more exclusive, but 57 was more populist. Punks, hippies, sex, drugs — it was super-eclectic in a unique way.”

Musician April Palmieri, a frequent performer at the St. Mark’s venue, said that the club was “an open house to express yourself. We were delighted to let loose and be ourselves.”

Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf were School of Visual Arts students when they became part of the scene. Haring performed, exhibited his art and curated a number of art shows there. Marlene Weisman, whose original artwork is in the MoMA show, remembers submitting her work to curator Haring.

“I saw a flier in the neighborhood inviting artists to submit,” she said, “and I brought him a few of my Xerox transfer pieces. Next thing I knew, I was in two of his shows.”

Scharf, who was showing his work at Club 57 when he was only 19, summed up the whole experience succinctly while sitting in his “Cosmic Cavern” installation: “It was a riot.”

When asked about his favorite memory, he replied, “I have too many — but most of them are on these walls.”

Artist and poet Valery Oisteanu, also exhibited, and curated, there.

“It was the last authentic bohemian club — a fast-paced multimedia affair, with video, film, music, art, performance,” he recalled. “Plays were written over the weekend and performed on Monday!”

He remembered spending an afternoon with Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, “painting the whole place, the walls, the chairs, the floors, just for a one-night show!”

Actress and performance artist Ann Magnuson, who curated the theatrical performances and managed bookings at the East Village club, as well as performed there, remembered one thing more than anything else: “Laughing!” she exclaimed. “And Wendy Wild — my happiest memories are of her. She is here in spirit.”

Scott Wittman mentioned the late Wild, as well, speaking of her and John Sex, also gone.

“The fact that they are in MoMA is both joyous and heartbreaking,” he reflected.

Keith Haring, of course, has been in MoMA for a while, but things were different back then. Henny Garfunkel, who was in several shows at 57, remembered going to a show of Haring’s “really huge” paintings and drawings at the club.

“They were selling for $100, and everyone said, ‘Oh, you really think so?’ ”

In the best tradition of that “Hey kids, let’s put on a show!” aesthetic of old Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland movies — but with drugs (“Oh, yes,” agreed April Palmieri) — productions were mounted with limited budgets but unlimited imagination.

Scott Wittman and Marc Shaiman (of Broadway’s “Hairspray” fame) produced a number of shows at 57, including their original musical “Livin’ Dolls.” But Wittman’s favorite was “The Sound of Muzak,” starring Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn.

“The Alps were on one side of the space and the convent was on the other, with the audience in the middle,” he said. “Every time the scene changed, everyone had to stand up and rotate their chairs.”

It took clubgoer Gene Fedorko a little while to process everything that he experienced at 57. He had just moved to New York City when he started going to the place.

“It was fabulous,” he said, “like Paris in the ’20s, but at the time, I didn’t think much of it. I just had fun. It was 25 years later when I said, ‘Holy F—! I lived through that?’ ”

Noted art dealer Jeffrey Deitch expressed a similar (but less colorful) sentiment.

“Even though I attended many events at Club 57,” he said, “this show is a revelation.”

Show curator Ron Magliozzi was pretty happy with the turnout on opening night.

“We’re told we succeeded in bringing the old spirit of the East Village back to life Uptown,” he said. “It certainly was a rocking time for three hours.”

And what to make of this incredible scene being enshrined by the art establishment? We’re going to give John Waters the last word on the whole affair, not just because he deserves it, but because, as usual, he’s summed it up perfectly: “Going to the MoMA exhibition was like attending an art reform-school dropout reunion in the principal’s office.”