BY SARAH FERGUSON | Parks Department officials got an earful Monday night at a community meeting to discuss a contentious plan to lower the fences around the playgrounds in Tompkins Square Park.

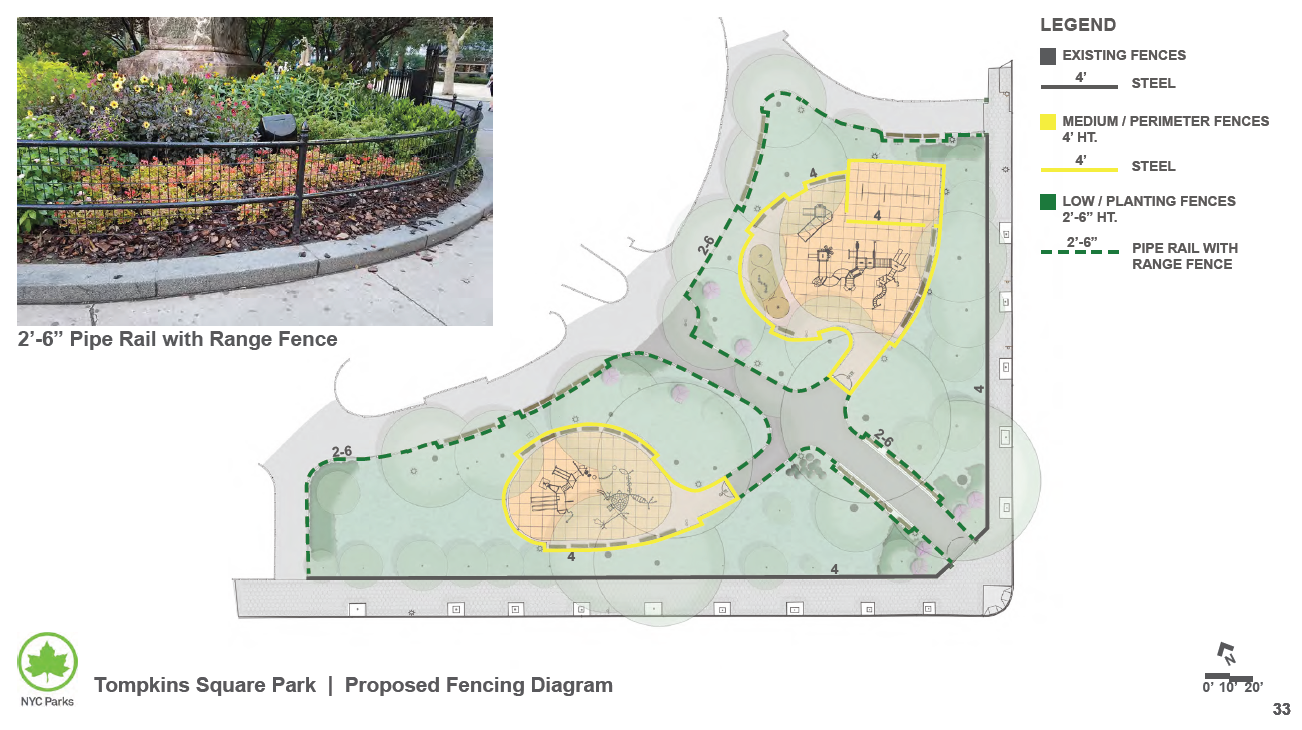

Dozens of parents and area residents turned out for the meeting called by City Councilmember Rosie Mendez. Most of them roundly denounced the city’s scheme to replace the 7-foot-high steel-bar fences surrounding the two playgrounds in the park’s southeast corner off Avenue B with new 4-foot fences.

Mendez has allocated $1.4 million to renovate the two playgrounds, which are heavily utilized by area schools and daycare centers. But she said she was shocked to find out that the city had added an additional $490,000 in funding to lower the fences around the playgrounds.

The plan by Parks also calls for replacing the 4-foot fences that line the interior park paths in this area with new 2-foot-6-inch-tall steel-tube fencing, similar to what is in place in Washington Square Park, and reconstructing the entry piers at the corner of Seventh St. and Avenue B.

The fence redo is part of the city’s new Parks Without Borders initiative to make parks more “open and accessible” by lowering or removing tall fences and shrubbery, expanding entrances, and adding lighting to improve sightlines.

Officials say the new design philosophy aims to reduce crime and other “negative behavior” by increasing access and visibility to “underutilized spaces,” while enabling police to more easily surveil the parks.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has dedicated $50 million to the program citywide — with most of the funds going to eight “showcase parks” that will be rehabbed in accordance with the design principles. Among them is historic Seward Park on the Lower East Side, which is slated for $6.4 million in improvements.

But Mendez and other local officials are up in arms about the Tompkins plan, fearing shorter fences around the Aveune B playgrounds could make it easier for kids to climb out — while also making them vulnerable to threats from vagrants and drug users who might enter after hours and leave behind used needles.

In an Oct. 6 letter to Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver, Mendez urged him to reconsider the playground fence heights in light of reports of increased violence among park denizens.

“For the last year and a half, there has been a higher incidence of vagrants in the park who are highly intoxicated with alcohol and drugs,” Mendez wrote. “We have reports from constituents and the Ninth Precinct stating that vagrants are increasingly violent and have attacked park visitors. On a daily basis, one may find drug paraphernalia and needles lying around.”

In December, Community Board 3 passed a resolution that “strongly opposed” the new playground fences. The new Ninth Precinct commander, Captain Vincent Greany, has also said he thinks it would be better to address the issues of homelessness and substance abuse in Tompkins first, before tackling the park fencing.

Mendez also said there was no need to improve access to Tompkins Square, which is already heavily used by diverse elements of the community.

“Let’s remember that the fences are there given the historical context of this park, which was in fact redesigned by the police and city after the infamous riots of 1988,” she noted.

At Monday’s meeting, William Castro, the Manhattan borough commissioner for Parks, sought to tamp down this mini-revolt against the new fence plan.

“This is what democracy is all about,” he remarked, saying the city was still open to community input.

“I’ve had experience with a variety of heights of fences,” added Castro, who has served at Parks for more than 40 years. “The problems you are raising, of kids climbing out of the playgrounds — it doesn’t really occur.”

Castro said the lower fences would actually improve safety in the park.

“The visibility is a real important issue,” he said. “It dramatically increases our ability to look into the parks and playgrounds. That allows police and PEP [Parks Enforcement Patrol] officers and parents to look into the parks.

“I used to run the PEP program in Tompkins, so I’m very familiar with the issues of criminal activity and people who try to hide,” Castro added.

In the opening presentation, architect Leslie Peoples showed images of the Avenue B playground redesigns, which will feature bright yellow and blue play equipment, some of it accessible to disabled children, as well as a new swing set and spray showers for the tot-size play area. The new fences would align with the height of the park’s existing 4-foot perimeter fence.

Peoples also showed images of other playgrounds — like those in Madison Square Park and Hester Street Playground in Sara D. Roosevelt Park — which she said already function well with shorter fences.

Reducing fence heights, she explained, is a way to provide “eyes on the park” from both police and passersby.

“It’s a natural form of surveillance. You don’t have to have this big wall in front of you,” she said, popping up a shot of the existing Avenue B playgrounds, which are currently surrounded by multiple fences, including the somewhat medieval-looking 7-foot steel fencing that encloses the play areas.

(At the initial scoping meeting for the playground redesign in November 2015, one parent reportedly said it felt a bit like a “penitentiary.”)

But such design ideals are at odds with how most parents feel, Mendez said.

“This neighborhood is home to people who come here to get trashed,” remarked a mother of two toddlers who said she regularly uses the Tompkins playgrounds. “If the gate in the playground on Avenue A isn’t locked, they will break bottles and pee in the sandbox and other careless things.

“A 4-foot fence does very little to discourage that type of behavior,” she added.

Castro pledged that the gates to the playgrounds would be locked each night, and that Parks crews would clean the spaces before reopening them to the public at 7 a.m.

“The police have increased patrols already to deal with a variety of issues,” he said. But the renovation budget does not include more money for maintenance or a full-time park administrator to keep an eye on things, like other parks have — plus the Tompkins maintenance budget is “already in place,” a spokesperson said.

Frank Gardner, a local dad and psychologist, asked whether the city had any data to prove whether environmental design can actually reduce crime.

“Frankly, I don’t believe it,” he said.

Gardner said lower fences and better visibility would only be effective in reducing “planned criminal behavior, not impulsive criminal behavior.”

“And that’s the problem we have in the park —people with drug and alcohol problems and mental illness,” he said. “Whether there is better visibility, I think, is irrelevant.”

Indeed, one father said he had been attacked by a mentally ill person while leaving the Avenue A park with his 4-year-old two years ago.

“It was scary, and it happened outside the playground, and was right on the curb,” said Jake Wolff. “That fence sort of makes us feel safe and protected, and if something, God forbid, were to happen to someone inside the playground… .”

Others took issue with the notion that lower fences would be adequate to keep their children contained.

“Kids do jump the fence if you’re in a lower-fenced area — my grandson does,” said Cyndi Kerr, who also raised two children here in the 1980s. “I personally feel a sense of security when I take my grandson to the park.”

Lower fences, Kerr said, would just encourage teenagers and drunk college kids to hop the fences at night and damage the new play equipment.

“They would go in and destroy it, vandalize it,” she said.

“Why can’t you spend the same money repairing things that are worn-out and broken? It doesn’t make any sense,” Kerr added.

Castro responded that the playground renovation and Parks Without Borders funds were capital funding and could not be used for expenses like repairs. But he did not know whether the funding could be reallocated for other capital projects.

Susan Stetzer, the district manager of C.B. 3, said she was speaking out personally as a “second-generation playground user.” Her own children grew up playing in what used to be termed “Impetigo Playground” on Avenue A, and now her grandchildren also use the park.

Stetzer questioned why the city was pursuing a top-down design strategy that was at odds with what the community wanted.

“We know our community,” she said. “Community-based planning — it works well for us now. We don’t need to change it.”

That view was echoed by K Webster, president of the Sara D. Roosevelt Park Coalition.

“It’s a lot of money for a no-win,” she said. “Why do it? There’s a reality on the ground that goes beyond design ideals.”

Webster noted that the playground fence at Sara Roosevelt is also fairly low. But that only works, she said, because the Parks station is adjacent, so staffers can keep an eye on things. Nevertheless, Webster said she and other volunteers struggle to keep the play areas clean.

“The issue is maintenance,” she said. “We have to remove needles and human feces and trash and homeless luggage on a regular basis.”

Indeed, for many parents, design aesthetics are beside the point.

“You’ve said the higher fences are like cages,” remarked one mother, who described herself as a lifelong East Village resident. “Well, we want to go into our cage and feel safe. We don’t want to look out — because lots of times there are things going on that we don’t want our children to see. Fixing something that isn’t broken is kind of a waste.”

Former C.B. 3 Chairperson Anne Johnson, who led the board during the Tompkins Square riot years, was even more strident.

“I want to know,” she said, “why you are pursuing this grandiose gentrifying scheme to lower the fences for all the new people who are coming in here to these fancy apartments, and not the people who are from the community and who know the deal?

“I want you to listen to us and not shove down our throats what we don’t want,” Johnson added.

Castro bit back at the notion that the fence plan was a done deal.

“We’re here to listen to everybody,” he insisted. “It’s not just going to end tonight.”

While Parks Commissioner Silver has been committed to implementing the PWoB design principles in all new park renovations, Castro said he would take the community’s feedback into consideration.

“I’m going to think about all this and talk to the commissioner the next day and then call you,” he told Mendez, adding, “I’m happy to come back.”