BY DENNIS LYNCH | Hoping to compromise with locals, the group behind a planned memorial to the 146 victims of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire presented a significantly toned-down design of the memorial at a public meeting at The Cooper Union on Thursday. But opponents only doubled down on their criticisms.

The architects of the memorial replaced the mirrored metal band that would run up the corner of the Brown Building, at Washington Place and Greene St., from the ground to the scene of the fire on the eighth and ninth floors with a matte stainless-steel band after nearby residents aired concerns that the reflective finish would cast a blinding light on the surrounding area.

Under the new design, only a strip at the top of the memorial would remain mirrored to draw eyes toward the building’s eighth and ninth floors, where victims of the blaze suffocated and leapt to their deaths.

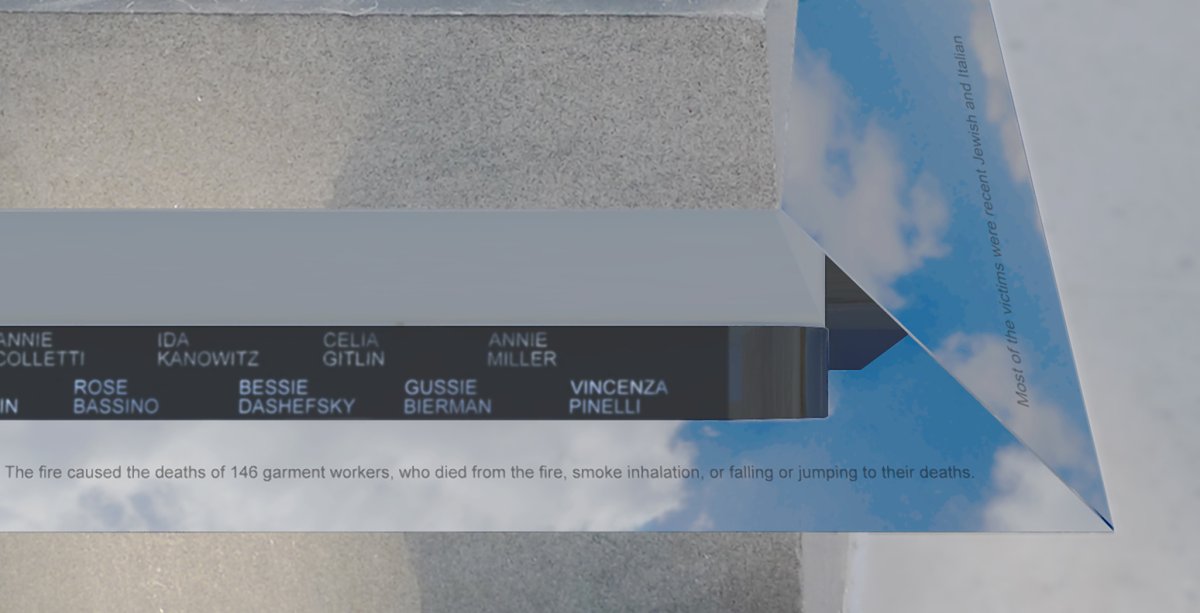

The rest of the memorial would remain the same — a reflective strip would run around the building, etched with the story of the fire. A non-reflective band with the names of the victims etched into it would run parallel overhead. The lower band would reflect the top band and the sky above, so that people could read both the story of the fire and names of the victims. A low-power LED light on the upper horizontal band would illuminate the outlines of the victims’ names at night.

However, the vertical strip of reflective metal planned at the top of the memorial still concerned residents. Architects Richard Joon Yoo and Uri Wegman repeatedly attempted to reassure them that the mirrored finish would be “no more reflective than a window.” They showed a simulation of what, according to them, would only be minimal reflection that it would project onto the residential building across the intersection.

One woman who lives on the ninth floor of that building said it would certainly draw her eyes to the memorial.

“I find it impossible to believe that reflections you expect to be seen all through the city will not bother me day and night more than the normal light that comes and goes on windows,” Barbara Quart said. “It seems it would be a major intrusion on my life and a number of us in the building. I don’t know why you have to have a beacon that calls out to the whole city.”

Others opponents, including the president of the Washington Place Block Association, derided the design in its entirety, and called it inappropriate for a memorial to a disaster that happened more than century ago.

The memorial “lacks the dignity, solemnity and gravitas that should characterize the memorial for the 146 people that perished in this tragedy,” Howard Negrin said, adding that the memorial’s eye-catching design was “incompatible” with the neighborhood character.

Negrin and many others alleged that the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition did not properly consult local stakeholders in the project’s design, which members of the memorial group said was not true. Negrin advocated for a subtler memorial, such as a plaque listing the names of the victims to go alongside the three plaques that are already now on the Brown Building. But coalition members disagreed.

“Nobody looks at those plaques. I’ve looked at those plaques every time I’ve walked by, but I’ve also watched everyone walk by ignoring them,” countered Daniel Levinson Wilk, a professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “This work of art will be so much more visible, will attract so much more attention, especially from younger people.”

Scrapping the idea and starting over was essentially off the table, coalition members said.

“We’ve compromised,” Joel Sosinsky said. “Their compromise is throw this out the door and start over — we’re not going to start over.”

The coalition’s president, Mary Anne Trasciatti, said the group would move forward with the basic design, but that the street-level night lighting and the matter of the reflective material at the top of the memorial were “still in play.”

The design, however, still has to make its way through Community Board 2 and gain Landmarks Preservation Commission approval before it could actually go up on the building. The coalition has not set a date for a hearing with either entity, and its president stressed that L.P.C., in particular, could require changes of the current proposal.

“I think, in any case, even if everyone here loved the design, there’s no guarantee this is what will be on the building,” Trasciatti said. “If we were to move to an Edwardian, Victorian or Ben Shahn-ian kind of design, that’s not going to happen. Those kinds of things are not likely to change.”

The group also needs to raise what they estimate needs to be a $1 million endowment to pay to maintain the memorial in perpetuity. Governor Andrew Cuomo allocated $1.5 million in state funds last December to help pay the memorial’s construction cost.

The horrors of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire prompted a sea change in labor safety laws in New York. Many of the victims —who were mostly poor Eastern European immigrants, primarily Jewish and Italian women — could have survived the fire, but a fire escape collapsed during the fire, the factory owners had locked the doors to one of the two stairwells to prevent material theft, and there were no sprinklers installed in the factory.

After the factory owners walked out of court with a slap on the wrist for their role in the tragedy, women laborers organized and successfully pushed for new laws regulating work hours and safety requirements, such as proper entryways and exits, sprinkler systems and fire alarm systems. Together the city and state adopted 36 such laws in the years immediately following the tragedy.