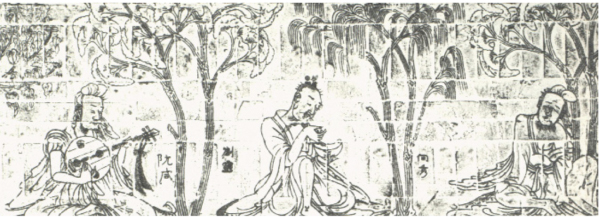

A portion of “The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi,” a rubbing of an impressed-brick mural from the Southern Dynasties period (420-589 CE), which will be included in the China Institute’s upcoming exhibit “Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks From Six Dynasties China.”

BY BILL WEINBERG | In a sign of Manhattan’s shifting cultural center of gravity, the China Institute has just moved from its longtime Midtown location to Rector St., just blocks away from the World Trade Center site.

The new office-tower digs may be a bit more sterile than the stately old mansion on 65th St., but the institute had “outgrown” its old home, said the organization’s president, James Heimowitz.

“We’ve gone from 9,000 to 52,000 square feet, with state-of-the-art classrooms and galleries,” he said.

An auditorium and exhibition space for pop-up art exhibits on the first floor are still being prepared. The classrooms on the second floor are already hosting events.

Prominently placed in Heimowitz’s office is a bust of Hu Shih — the pioneering scholar and statesman, modernizer in education and literature, and the first Chinese national to receive a Ph.D. from Columbia University. He co-founded the China Institute with the American philosopher John Dewey and others in 1926.

“The first mission was to help Chinese be more successful in academia in the United States, to provide a place to acclimatize,” said Heimowitz. “Chinese students at that time were excluded from social events and dorms, so the institute was a place to meet and socialize.”

The China Institute was actually first launched with Boxer Indemnity funds — reparations that the Chinese government was made to pay to foreign powers after the 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion, but which the U.S. later allowed to be used for the education of Chinese in this country. The institute was given the Frederick S. Lee House at 125 E. 65th St. by publishing magnate Henry Luce in 1944. That same year, it was accredited as a nonprofit educational institution by the New York State Board of Regents.

Today the mission is a little different — and aimed more at Americans than Chinese resident scholars and expats.

“China and the U.S. are the two most important countries on the planet for the coming time,” Heimowitz explained, describing a central part of the new mission being to “help Americans be more comfortable with China,” through programs in language, culture art and history.

The institute is currently engaged in “professional development” of public school programs with the New York City Department of Education. A recent program the institute helped develop around the children’s book “We All Live in the Forbidden City,” by Chiu Kwong-chiu, about life in imperial China, was used in cities across the U.S. and in Canada.

An upcoming exhibit at the new gallery will feature archeological treasures from the Six Dynasties period (roughly 220-590 CE). Lunar New Year celebrations at the institute last year featured the actor Liu Xiao Ling Tong, famous in China for playing the role of the Monkey God in the 1980s TV series based on the Ming dynasty epic, “Journey to the West.”

On a more politically sensitive note, the institute this May marked the 50th anniversary of the start of the Cultural Revolution with film and discussion. But criticism of this period of chaos and strife — even if it was unleashed at the whim of Chairman Mao — is permissible in contemporary China.

Last September, the institute hosted a dinner presentation for China’s new president, Xi Jinping, in Seattle. Heimowitz stated clearly that the institute seeks to present Chinese perspectives in “unadulterated and direct form,” as an alternative to “news through a Western lens.” He added: “Let people decide for themselves.”

“Through revolutions, liberations, cultural revolutions, all of it — we’re still here promoting cultural understanding between the U.S. and China,” he summed up.

The Six Dynasties exhibit — with relics on loan from museums in Nanjing and Shanxi — is being curated by Willow Weilan Hai, the institute’s gallery director. She was trained as an archeologist at Nanjing University — among the first generation of Chinese archeologists when academic life resumed after the end of the Cultural Revolution. She participated in excavation of a Neolithic site on the Yangtze River before coming to New York in the late 1980s.

“The Six Dynasties were a chaotic period, but they saw intellectual achievements in art, literature and music that are still important to today,” she said, taking obvious pride in the new gallery’s inaugural exhibit, opening Sept. 30. By then, the institute’s permanent entrance at 100 Washington St. should be open — just around the corner from the 40 Rector St. entrance now being used while the ground-floor galleries are prepared.

“We are building a new cultural center for New York,” she said, pointing to the Financial District’s recent emergence as a museum district. China Institute is now the third such entry, after the 9/11 museum and the Smithsonian-affiliated National Museum of the American Indian in the old Customs House on Bowling Green.

Hai said, with a laugh: “We’re going to build up something new and challenge Midtown.”