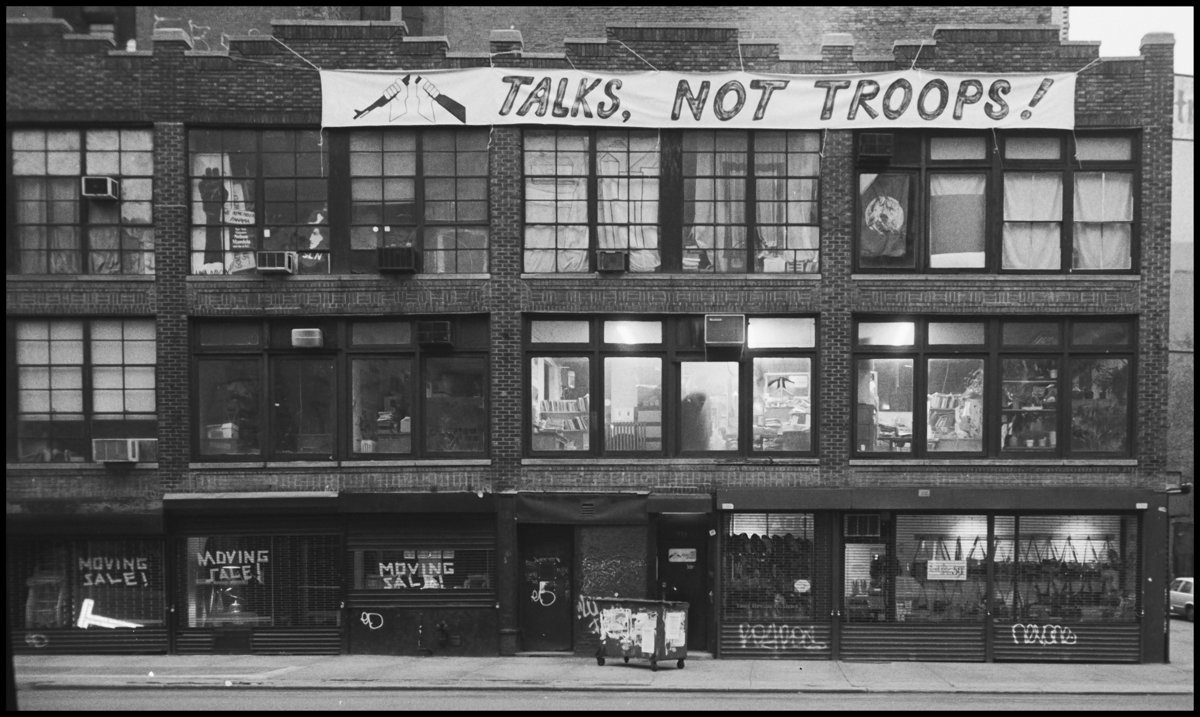

BY BILL WEINBERG | The night of Thurs., May 5, was a bittersweet one for me. For probably the last time in my life, I crossed the threshold of 339 Lafayette St., for a “Moving the Movement” farewell party. I was bidding adieu to the building that three generations of activists had affectionately called the “Peace Pentagon.”

The gathering was confined to one room of the three-story structure, with construction tape barring access to the other rooms, and the halls deserted. It was an eerie feeling.

The first time I entered the building at the corner of Lafayette and Bleecker, I was in my senior year of high school. It was 1980, Reagan’s election was imminent, the Iran hostage crisis and Soviet invasion of Afghanistan dominated the headlines, and the big lurch to the right was in frightening progress.

President Carter, who had been elected on a pledge to pardon Vietnam-era draft resisters, capitulated to the new bellicose zeitgeist by bringing back draft registration. I was in the first crop of 18-year-olds to have to register with the Selective Service System since 1973. This precipitated my first activist involvement — a student anti-draft group. Through this, I was inevitably drawn into the orbit of the War Resisters League — the venerable pacifist organization that grew out of anti-draft efforts in World War I, and was the anchor tenant at No. 339.

There hasn’t been a year since then that I did not return to the building multiple times. Just my own interactions with the place will give a sense of the intensely diverse activity it hosted. It was a nerve center of organizing for the massive nuclear disarmament march of June 12, 1982, which brought one million people to the Great Lawn of Central Park, and in which I was a young foot soldier.

By fate or coincidence, much of my life was for years wound up with Room 202. First, it hosted Sound & Hudson Against Atomic Development — the SHAD Alliance — with whom I agitated to close down the Indian Point nuclear plant in Westchester County. Later, the room housed my longtime activist home: the Libertarian Book Club (a left-wing anarchist formation first founded by refugees from Axis Europe in the ’40s), and its sibling organizations. These included the anarcho-syndicalist Workers Solidarity Alliance and Neither East Nor West, which built solidarity with antiwar and anti-nuclear resisters in the East Bloc.

Later, in the ’90s, Room 202 hosted another organization I worked with, the Amanakaa Amazon Network, which was led by Brazilian ex-pats and worked to support the rubber-tappers and indigenous peoples resisting destruction of the rainforest.

I was in the outer orbit of groups hosted in other offices in the building — the Nicaragua Solidarity Network of Greater New York, the Socialist Party and of course W.R.L. itself, which occupied the big corner office on the second floor. I more than once used the building’s AJ Muste Memorial Library for historical research on Gandhi and other nonviolence struggles of the 20th century.

The AJ Muste Memorial Institute — generally referred to as “the foundation,” and named for one of W.R.L.’s stalwarts from the start of the Cold War until his death in 1967 — actually owned the building. After years of grappling with whether it was worth it to invest money in urgently needed repairs of the deteriorating structure, last October the foundation took the painful decision to sell the property. The New York Times reported that developer Aby Rosen purchased the building for $20.75 million. Although current zoning allows office or commercial space, residential condos may be in the offing if a “variance” is granted.

After the farewell party, I sought out the only person I know who was around when W.R.L. moved into No. 339 back when I was still in first grade: David McReynolds, for years a central figure in W.R.L. and a two-time Socialist Party presidential candidate. He, so to speak, was present at the creation.

McReynolds first got involved in W.R.L. in 1960, when the organization was in an office at 5 Beekman St. that it had inhabited since World War II. At that time, peace activism was at a low ebb. But it was soon on the upswing again over “Vietnam and the nuclear test issue,” McReynolds remembered.

W.R.L.’s importance was clearly demonstrated one night in 1969, when the offices suffered a break-in and were ransacked. McReynolds said he’s certain it was the F.B.I. or another government agency, and added that he was flattered by the burglary.

“I thought nobody was paying attention to W.R.L.,” he said wryly.

The break-in precipitated the move to No. 339, because the landlord at the Beekman building got scared and kicked them out after that. W.R.L. bought what would become the Peace Pentagon for $58,000.

Back then, there was a locksmith and a hot-dog stand on the ground floor. (Later, post-gentrification, the ground-floor storefronts would be rented to boutiques and a vintage clothing store.) In 1975, W.R.L. founded the Muste Institute, to be the legal owner of the building and serve as a nonprofit channel for donations. That’s when McReynolds said the building was conceived as a “Peace Pentagon, where other groups could rent space at low cost.”

And now that era has come to an end — at least as far as the property at No. 339 is concerned. McReynolds admits there were “a lot of hard feelings and struggle” over the decision to sell the building.

“I was one of those who opposed the decision to sell,” he said — but hastened to add: “I’d left the Muste board by then, so I had nothing to do with the decision to move out.”

McReynolds also retired from W.R.L. staff in 1999.

“My only link to the building was to go in and feed the cat, Rusty,” he said. The feline was named for his old comrade Bayard Rustin, the civil rights leader and also a W.R.L. fellow traveler for many years.

Judith Mahoney Pasternak, a writer, veteran W.R.L. board member and former editor of the group’s magazine, the Non-Violent Activist, called me from Paris where she now lives to give me her own thoughts.

“Yes, of course many of us were sad, because so much history had happened there,” she said. “But in the end it was the only possible solution for a decaying building.”

The Muste Institute and W.R.L. will soon be moving to new premises — at 168 Canal St., on the corner of Elizabeth St. But it will be renting, not owning, and in considerably less space. Eventual purchase of a new building is apparently being contemplated.

McReynolds and I both live on E. Fourth St., just a few blocks from No. 339, and I admit to a pang at the loss of another pillar of alternative culture in the neighborhood. McReynolds, who had much more of his life wound up in the building than I ever did, seemed more accepting of the change.

“I’m glad I don’t have to feed the cat anymore,” he said.

Rusty has found a new home with a family in Baltimore.