BY SARA HENDRICKSON | New innovative admissions policies have been instituted at a handful of the city’s public schools to combat increasing segregation and narrow the intractable achievement gap.

On the evening of Mon., Jan. 11, 160 community members gathered in the gym of the Clinton School for Artists and Writers, at 10 E. 15th St., to learn about these novel approaches and collaborate on shaping the admissions policy for the new Morton St. middle school, which will be opening in fall 2017.

The meeting was sponsored by the 75 Morton Community Alliance, Community Boards 2 and 4 and Community Education Council 2. Parents from 23 schools attended, along with several professional educators and representatives from the Department of Education and local politicians.

The event followed a series of group envisioning sessions and fruitful collaborations between the community and D.O.E. over the last several years to create this large new school for 600 to 900 students and 60 to 100 District 75 students with special learning needs.

Holly Noto, a 75 M.C.A. member and professional facilitator, kicked off the meeting.

“You have a voice,” she told everyone. “This is your chance to put a new dish on the menu.”

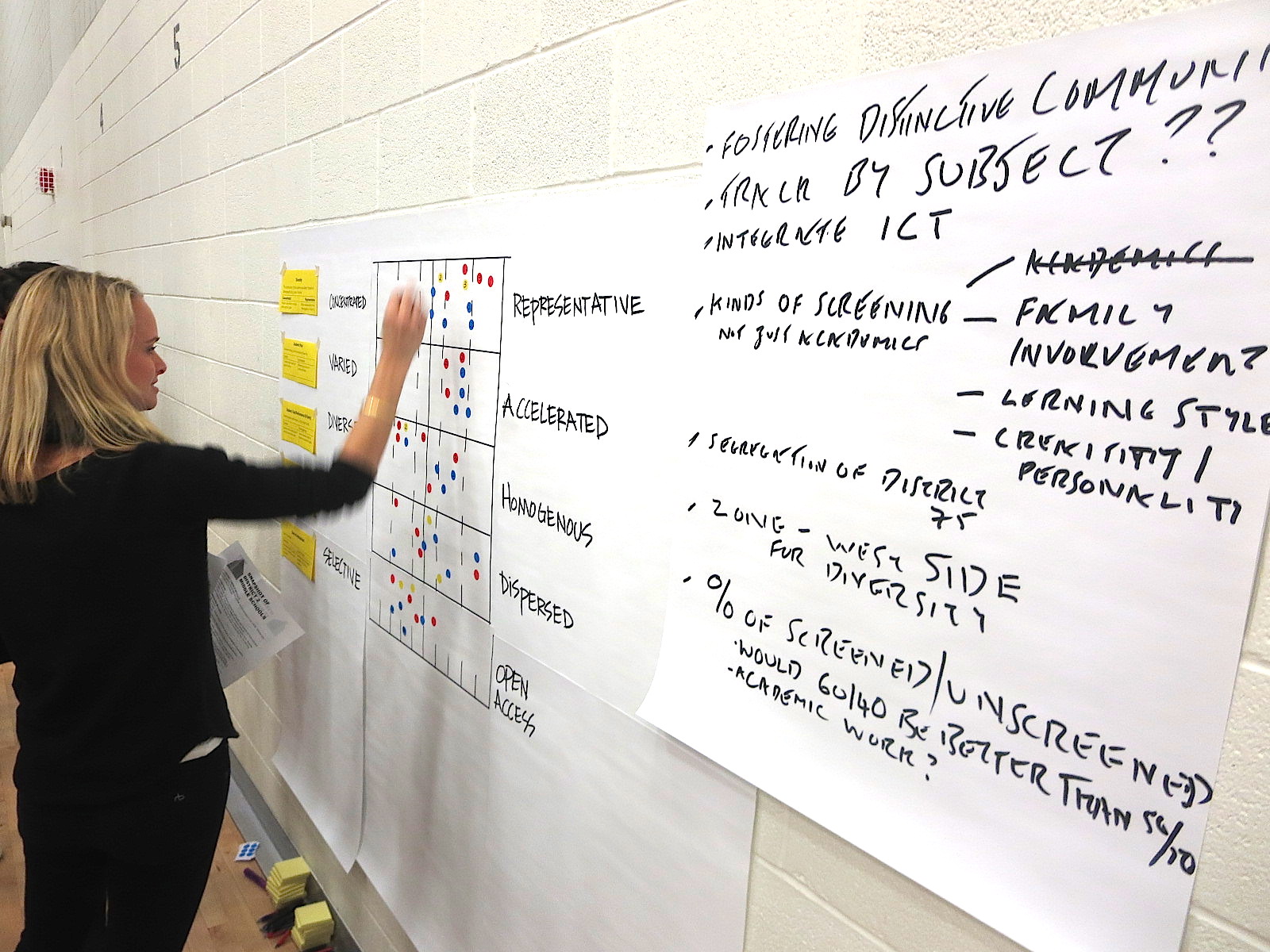

Continuing with the food analogy, which proved useful throughout the evening, Ned Elton of 75 M.C.A. walked the audience through six hypothetical school models created by various admissions methods.

The “apple” school was purely zoned with no screening and one academic track. This would likely create a school that is easy to get into (since students living in the zone who apply are automatically admitted), with fairly low diversity (the Morton St. school is located in the affluent and homogeneous West Village), and a varied academic pace within one program for students at different academic achievement levels.

The “carrot” school, in contrast, was unzoned, with screening based on academics, behavior and the student’s expressed interest in the school, and with one academic track. This would likely create a school that is difficult to get into, with minimal diversity, and an accelerated academic pace for high-achieving students coming from neighborhoods near and far.

The “blueberry,” “eggplant,” “dandelion” and “zucchini” school models had other admissions methods and single- or dual-track academic programs, which created schools with characteristics falling somewhere in between the “apple” and “carrot” ends of the spectrum.

Before breaking into discussion groups to deliberate on these models, educators from city schools shared their experiences, offered advice and made some impassioned pleas.

John O’Reilly, principal of the Academy of Arts & Letters in Brooklyn, described how his K-through-8 school in Fort Greene was being impacted by a wave of neighborhood gentrification, with thousands of new residential units and hundreds of affluent white families vying for a small number of seats. After much advocacy from the school’s leaders and community, D.O.E. granted approval late last year for a “diversity set-aside” admissions method, whereby students eligible for free and reduced lunch — indicating their family lives at or below the poverty line — receive priority for 40 percent of the school’s seats.

“We’re constrained by the laws of the land to talk about race, but I can talk about socioeconomics, which has been a vital piece of our school,” counseled O’Reilly.

His colleague, Assistant Principal Meg Crouch, was emphatic.

“All the research shows that an integrated, diverse school narrows the achievement gap,” she said. “So if you want students to prepare to be strong adults in a democracy, advocate for diversity based on socioeconomics and learning needs.”

Principal Maggie Siena from the Peck St. School addressed innovative ways to screen students for admission. For example, she encouraged consideration of new screening filters, such as artwork or group projects.

“Students may be strong, but not hit the metrics,” she said. “So this may allow you to see qualities in kids and to have a diversity of learners.”

Siena also pointed out that parents of high-achieving students have become increasingly “nervous about their children applying to homogeneous schools,” so an admissions policy ensuring diversity may be important to attract those applicants.

In addition to admissions priority for low-income students, other new methods include set-asides for English Language Learner students, students with a range of low, medium, and high state test scores, students from specific elementary schools, and students with incarcerated parents.

There are only four zoned schools out of the 23 middle schools in District 2, but none are 100 percent zoned. The largest are Baruch and Wagner, which have 1,000-plus students and use a hybrid admissions method. A portion of seats are filled based solely on a student’s residency within the zone. In addition, a portion of seats are filled based on screening criteria, which may include test scores, report cards, attendance, interviews, the student’s rank choice for the school, and other metrics. Both schools offer two academic programs — an “academic progress” track and a more accelerated “special progress” track — and students can apply for one or both programs.

“A zoned middle school is not what you think of as a neighborhood school,” explained Shino Tanikawa, the president of C.E.C. 2, in her refresher course on middle school admissions.

Elton of 75 M.C.A. clarified that a “zone” for a city middle school is actually larger than people might think.

“It’s not a matter of the school being five blocks away,” he said. “It could be two express subway stops away since it’s really about the commute.”

A significant portion of School District 2 on the West Side from W. 23rd to W. 59th Sts. and within easy commuting distance from the Morton St. school is, in fact, unzoned. This evolved, in large part, from three schools in Hell’s Kitchen that were formerly K-through-8, but phased out their middle school grades over the years.

To explore the possibility of establishing a new middle school zone for the Morton St. school, District 2 Superintendent Bonnie Laboy recently initiated the zoning process to start the clock ticking on the “prescriptive procedure,” which ultimately falls under the purview of C.E.C. 2. The process includes zoning proposals and possible revisions from D.O.E, interspersed with C.E.C. 2 meetings and public hearings, and culminating with a final vote.

To stay on track for 75 Morton’s timeline, a vote of six of the 10 C.E.C. 2 members approving the new zone would have to take place by this April. Tanikawa explained that even if 75 Morton becomes a zoned school, given its large size, it is not likely to be 100 percent zoned since that could risk seats going unfilled.

After becoming well-versed in a long menu of admissions methods, attendees separated into a half-dozen break-out groups to come up with new admissions recipes and deliberate on the six food-based school models.

One break-out group discussed the potential new zone as a way to achieve diversity.

“I like the idea of going down the West Side with a new zone to pick up different neighborhoods — just follow the E train,” suggested Lowell Kern, whose two children attended P.S. 11 in Chelsea and are now in high school and college.

Questions about what screening filters to weave together and how to define diversity dominated many conversations.

“The D.O.E is ready to allow more schools to define diversity,” Tanikawa had advised the groups.

For example, some asked, could children’s creativity and learning styles be screened since information is processed by students in different ways? Could family involvement be screened since parent engagement is closely correlated with strong schools? Greg Regaignon, father of a fourth grader and a seventh grader, worried that “family involvement could be a proxy for family income — like volunteer hours for parents who can afford not to work.”

After good, spirited debates, each participant ranked the top three school characteristics that mattered to them most and where on the spectrum they would like to see those characteristics for their ideal middle school. A final vote was cast on their way out the door for one of the six school models, leaving people to wonder which one the community would coalesce around — “zucchini?” “eggplant?” “blueberry?”

It did not take long to find out, as tallies and take-aways from the session were presented the following night at the Jan. 12 C.E.C. 2 meeting. Although the community was somewhat agnostic on zoning and showed about equal support for single- versus dual-track academic programs, there was significant preference for using two admissions methods. This approach could create a school with characteristics deemed most important by the community: a strong academic pace, plus diversity — diversity created by having students with different socioeconomic backgrounds, academic achievement and learning styles.

Sharing this vision with D.O.E. will be the next step along the path of opening the Morton St. school 18 months from now.