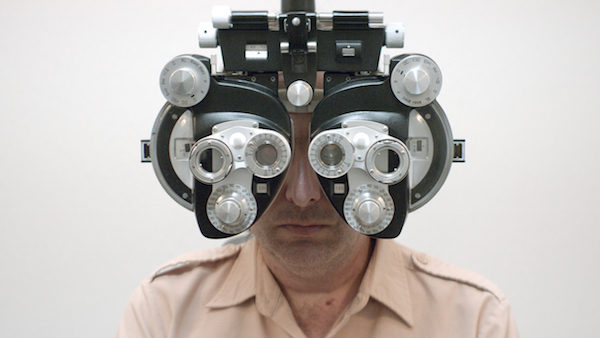

BY SEAN EGAN | Rick Alverson’s brilliant new feature, “Entertainment,” is an emotionally overwhelming sensory experience, which will leave those who can handle its unflinching bleakness dazed, confused, shaken and depressed. And Alverson wouldn’t have it any other way.

“We’ve been taught for three quarters of a century in the United States and in American popular cinema to read our films in a traditional literary, narrative style, and essentially we’re looking to unpack that experience,” Alverson says. “What movies seem to bring, the potential of them is sort of in this tonal, temporal experience. The intellect being stimulated and activated and engaged could be a wonderful by-product of that, but you know, I think that it mostly is engaged when the experience doesn’t fit neatly into those prescribed categories; when the intellect isn’t just an arbiter of and a reader of the film, and has to wrestle with what the content is, and what the form is.”

The film’s “plot,” as it were, concerns a character known simply as the Comedian. Played by Gregg Turkington (who co-wrote with Alverson and alt-comedy mainstay Tim Heidecker), the Comedian cuts a prickly but tragic figure, marching through the desert on a tour of dead-end clubs and dive bars. When not performing, he skulks around in near-silence visiting underwhelming tourist traps, and leaves his estranged daughter daily voicemails that go unanswered.

Onstage, however, he springs to life, wearing an oversized tux and cradling drinks, delivering material (as incredibly dated as it is blue) in a nasal whine, with stilted timing that all but guarantees audience confusion and/or hostility. It’s a riff on Neil Hamburger, Turkington’s longtime anti-comedy performance art standup persona that Alverson and co. expand upon here. Juxtaposing the Comedian’s ill-received performances and his miserable personal life allows the protagonist to slowly unravel, and creates the mounting existential dread that provides the thrust of the film’s narrative.

“Even more than sympathy, I think it’s a character that’s pitiable, which I think, as audiences, is something that’s even more attractive to us, because it allows us to elevate ourselves in relation to this person,” Alverson comments on the decision to work from the Hamburger archetype and explore his off-stage identity.

Almost as significant a character as the Comedian is the barren, oppressive sprawl of the western desert itself. Alverson admits to using motifs from American popular cinema as “raw materials” to shape the film’s structure, from the “stereotype of the spiritual journey in the desert, to the unlimited potential of the west,” and also notes his “obsessions and interests” that worked their way into the movie.

“One of them is an American utopian bent — you know, this idea of the unlimited potential of things,” the director reveals. “And I’m obsessed with the idea that that’s the source of a lot of, if not all our global problems, is the outsourcing of this dream, that can’t expire, that has no limits or edges. You know, when the world is full of limitations, and limitations are beautiful and necessary.”

As a deconstruction of the utopian myth of the west, it plays on the tropes of road movies admirably — and it’s clear its uncompromising, iconoclastic style shares some DNA with ’70s-era American independent cinema. “Five Easy Pieces” is even directly name-checked, though with its dream-like segues, emphasizing of sound and music over dialogue and expressive use of color it calls to mind another Bob Rafelson joint — the psychedelic fever dream/Monkees vehicle, “Head.” Overall, the formal mastery on display creates an uneasy, immersive atmosphere of quasi-hallucinatory isolation.

“Dialogue is not a narrative driver in any of my movies, and it won’t be, largely because I have this aversion to this unpacking and reading of the thing, and being essentially pulled by the author,” Alverson explains.

“The intention was to deal with that totally formally as opposed to narratively,” he continues. “I think that the thing was made to be slippery. It starts off very naturalistic, and you do lead it like a traditional narrative, and everything becomes apparent. It’s very one-dimensional and very simple and standard, about the journey and this sort of thing. But then it becomes slippery and harder to actually wrestle out a compact meaning or experience of the thing, so that it becomes more surreal.”

Indeed, trying to pull out a succinct lesson from the movie is difficult. A cousin played by John C. Reilly seems to be a warning against compromising or commercializing art, and a crass clown (Tye Sheridan) on tour with the Comedian is a stand-in for the empty, debased entertainment people regularly consume. For his part, Alverson sees the film as something of a “welcome swan song to the white, European, male dominant culture that we’ve had for centuries,” and hopes the film makes its audience consider the impact entertainment has on them and the world at large.

“We outsource this concept of limitless American potential, and the attainable American dream for all of the population, which is absolutely impossible. So, you know, I think that in our entertainment and our media, is a tool by which that narrative is facilitated,” Alverson explains. “If we don’t think every time we turn on a show on Netflix, or television, or click on a story on a page that it’s not promoting or selling something, whether it’s a concept, or an ideology, or goods, then we’re kidding ourselves.”

Alverson’s view isn’t entirely nihilistic however, as he recognizes there’s “the promise of art as something that’s distinct from disposable entertainment” — though as a caveat, he believes art should “upset and animate and have some sort of constructive potential.”

“Entertainment” upsets and challenges both its audience and its characters in the best of ways. Throughout the film the Comedian repeatedly brays the question “Why?” as a setup to his hackneyed jokes, becoming something of an obnoxious catchphrase. But as things progress, the phrase starts to sound less like a joke, and more like a desperate plea for anything to make sense in his life — and a cue for viewers to question what they’re watching. And like the God of his film, Alverson offers no easy answers to this inquisition.

“I’ve taken this approach to not so much talk about the content of the thing, because I think there’s this imbalance where all we talk about is content. You read ninety percent of criticism of movies, everybody just says, ‘This is what something’s about,’ ” Alverson claims. “Well what did you see and hear? That’s the experience. It’s a little frightening because there’s something happening there that people seem to be unaware of, that’s what they’re seeing and hearing — the actual physical experience of the thing.”

“Entertainment” runs 102 min. Opens Nov. 13 at Landmark Sunshine Cinema (143 E. Houston St. btw. First & Second Aves.) and On Demand. For tickets and info, visit landmarktheatres.com/new-york-city.