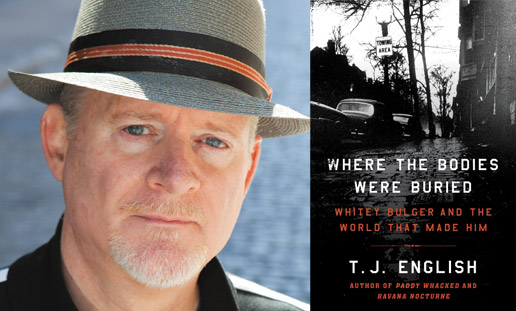

BY JACK BROWN | Distinguished crime journalist and Village resident T.J. English has written an authoritative and entertaining account of the rise and fall of Boston’s notorious former crime in his new book, “Where the Bodies Were Buried: Whitey Bulger And the World That Made Him” (HarperCollins).

The year 2013 was a gut-wrenching one for Boston. There was a terrorist bombing near the finish line of the marathon in April. The trial of 16-year fugitive gangster James “Whitey” Bulger began June 12. The trial dredged up and exhumed the depraved parade of heinous crimes committed by Bulger and his associates.

But perhaps there was no greater offense committed against the people than that by the Department of Justice itself. Joe Salvati did 30 years in jail for a murder he and three other victims of the Confidential Informant Program did not commit. Salvati was convicted by the bogus testimony of Joe “The Animal” Barboza in September 1967. The ends-justify-the means approach was to dismantle the New England Mafia.

In fact, Bulger, like Barboza, was a top-echelon confidential informant.

“The prosecutors wanted it to appear as if what happened to Joe Salvati had nothing to do with Whitey Bulger,” English writes. “Perhaps the entire criminal justice system was a grand illusion.”

Teresa Bond, who was a young girl when her father, Bucky Barrett, was murdered, got to Bulger with forgiveness during an impact statement uttered with near kindness.

“I just want you to know that I don’t hate you,” she said. “I hate the choices our government has made in allowing you to rule the streets and perform horrific acts of evil.”

Bulger — who, in fact, disliked being called Whitey — and his brother Billy dominated Boston politics and crime for more than 20 years. Billy became one of Massachusetts’ most powerful politicians, serving from 1978-96 as state Senate president.

With his C.I. F.B.I status, his brother’s influence and his control of the gang, Bulger seemingly hovered above the law. And he took full advantage.

English uses the trial as his format and diverges to provide historical and biographical background and penetrating insight. His writing is fair, balanced and authoritative. He also employs a wry sense of humor. He refers to Billy O’Shea, a trusted former Bulger business associate, as “Kermit the Frog’s aging Irish Uncle.”

Some agents, like handlers H. Paul Rico and John Connolly, come from the same social milieu as Bulger. They readily become thick as thieves. They also wind up in jail — Connolly, a seeming scapegoat to F.B.I damage control. But as English concludes, “The system protects itself.” Which begs the question: What is needed to protect “We the People” from the system?