BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | La Plaza Cultural was a sea of purple on Sat., Sept. 26, as more than 150 people gathered for a memorial to legendary gardener Adam Purple.

Chalked on the asphalt pavement in the garden’s center was a pinkish-purple drawing of Purple’s own magnificent Garden of Eden, with its concentric circles of plantings and double yin yang symbol at the center.

Purple died at age 84 on Sept. 14 while biking over the Williamsburg Bridge. He may have been returning from shopping for natural food in the East Village, heading back to the Time’s Up space in South Williamsburg, where he had lived with the bicycling / environmental group for the last three years. The cause of death was an apparent heart attack.

Speakers at La Plaza praised him as a visionary environmental pioneer, while at the same time fondly recalling him as famously quirky hippie who stubbornly stuck to his ideals.

At its peak, his lush garden, at Forsyth, Stanton and Eldridge Sts., grew to 15,000 square feet. He and his wife, Eve, fertilized it with horse manure collected in Central Park — and also their own excrement, which Purple called “night soil.” He and his family ate the food grown in the garden and shared it freely with neighbors.

But in 1986, in a devastating blow to Purple, the city bulldozed the garden to make way for a low-rise public housing development.

Purple was apparently estranged from his family, none of whom were at the memorial. There also did not appear to be any of his former Purple People present — devotees of his who used to wear purple nonleather clothes and were vegetarian, like him.

One of the speakers, Quent Kelleher, was an 11-year-old kid on the Upper West Side when he met Purple in Central Park and wound up helping “move bricks” in the ever-growing Garden of Eden. Kelleher said he was the only friend present at Purple’s “green burial” at a special environmental cemetery in Upstate Ithaca.

Kelleher later showed The Villager a photo on his phone of Purple’s body about to be lowered into the ground — he was wrapped in a white shroud and tied with rope to a plywood board. On his chest were a clutch of purple, white and yellow flowers. There was a brief, upbeat ceremony with the cemetery workers.

“There were no prayers,” he said. “We said poems. He was an atheist. … We laughed and giggled.”

“He was not practical,” Howard Brandstein, executive director of the E. Sixth St. Community Center, said of Purple. “He was a messiah. The Garden of Eden had to die for other gardens to live.”

In other words, the high-profile battle to save Purple’s garden raised awareness of the Lower East Side’s other gardens and the need to defend them.

Purple lived in an abandoned tenement on Forsyth St., but he never allowed it to become a community like the neighborhood’s squats.

“A few guys tried to live with him,” Brandstein recalled, noting it didn’t work out.

“He said they were vegetarians — but they wouldn’t s— in the garden,” he said to laughter. “He set a high bar.”

Listening in the crowd, Frank Morales, a former leader of the squatter movement, knowingly remarked to those within earshot, “He didn’t want anyone else in the building.”

Summing up his thoughts of Purple back when he met him in 1978, Brandstein said, “This guy’s incredible, but he’s kind of nuts — but he is a kind of messiah.”

Another speaker, Jacques, recalled how he came upon the stricken Purple on the bridge and got the word out.

“I was going up the bridge, where I encountered a lot of people trying to resuscitate someone,” he said. “I suddenly realized it was Adam Purple. I was told that about 15 minutes before there were two people giving him CPR trying to save him.”

He called his friend Bill Di Paola, executive director of Time’s Up, who spread the news.

Jacques said he had been among a group of people who went into Purple’s building back in 1999 right before the city demolished it, which is how he knew about him.

Carmine D’Intino, a longtime friend of Purple’s who lived with him at various times, hailed him as an “hombre de la calle — a man of the streets.”

“People wouldn’t harm him when he walked down the street,” he said.

D’Intino then broke into a heartfelt a cappella rendition of “When I’m Gone,” by the late protest singer Phil Ochs.

“Adam was sort of the living embodiment of the principle that lands that are abandoned by the landlords return to the inhabitants of the area,” said journalist Bill Weinberg, who leads tours of the neighborhood’s radical history.

“Adam’s garden was going to continue to expand indefinitely to the other blocks and the neighborhood and through the city,” Weinberg said. “Very visionary — or very eccentric — depending on your point of view.”

As they were gathered in the tranquil green space at La Plaza, featuring four towering trees, two of them graceful willows, Weinberg contrasted its fate with that of the Garden of Eden. Although the city succeed in razing Purple’s garden in the middle of winter in 1986, the next year it was a different story when La Plaza, at E. Ninth St. and Avenue C, was similarly targeted for housing, Weinberg recalled.

“The community organized — and we won,” he said, as the crowd applauded.

But Purple wasn’t perfect, noted Marlis Momber, the veteran Lower East Side photographer. She noted that he opposed abortion, sending a ripple of disapproval through the listeners. He wouldn’t let her take his photo at first, she said. And don’t forget the legendary female gardeners, she added, referring to Carmen Pabon, “The Mother Teresa of the Lower East Side,” who used to feed the homeless at her garden on Avenue C.

In his turn at the microphone, Morales, while holding purple flowers, said, “Adam was the most thoroughgoing revolutionary I ever met — the politics of s—! He was so diverse in his interests, he was so wide. Emerson, Whitman, Buddha, Jesus, Marx…Groucho…he was all of it, and he was so incisive.

“I’m still in denial,” he said of the larger-than-life figure’s passing.

“It’s good to see the family,” he told the tight-knit activist crowd gathered in the garden.

Maria Batas was a School of Visual Arts student when she interviewed Purple years ago for a project and was blown away by the encounter.

“He was intellectual, funny, very cryptic and had a lot to say,” she said. “He was a genius.”

Chris Flash, publisher of The SHADOW, called Purple an “urban survivalist.”

“He showed me how to make soil from manure and sawdust,” he said. “In winter, I was with him once and I was freezing, and he was just wearing a T-shirt. I admire him living on his own terms — stubborn, curmudgeon.”

Larry Friedman was a student at Stuyvesant High School when he moved into Purple’s building at 184 Forsyth St., paying around $50 a month for oil to heat his stove.

“I had oil and we had water,” he recalled, “and he was working on electricity. He stole electricity from the street — and we had electricity. I studied with the stove for warmth and the top flames for light.”

Living with Purple in the crime-ridden war zone of the Lower East Side back then, helped toughen up the teen. Friedman had grown up in public housing in Inwood but had to leave his family situation. At first, for protection, he slept against his door, which didn’t have a lock yet.

“When I was afraid of the junkies, he said, ‘Listen to the crickets.’ Now there were crickets in the backyard,” Friedman recalled of the garden’s magic. “He said, ‘When the crickets stop making noise, someone’s in the garden.’”

Friedman, today a physician’s assistant at Beth Israel Hospital, also changed his diet due to Purple.

“He took in a kid who didn’t know from vegetarians,” he said. “Now I’m a vegetarian.”

Friedman had unique insight into Purple from living with him. He saw one of the gardening icon’s relationships flame out.

“There was Eve I and Eve II,” he noted. “Eve I started dancing topless. She wanted to make money for their daughter, Nova Dawn, and move away. She did it. I heard her say, ‘I made $1,000 last night!’ My girlfriends didn’t have to babysit anymore because she moved away. That was the only time I heard them fight.”

Then there was what Friedman dubbed “The Year of the Weed.”

Pointing to one of the rings on the Garden of Eden drawing on the ground, he said, “It was all weed. The police came and filled up their car with the weed. They had to get a paddy wagon, too. The junkies were running in and grabbing plants, dropping dirt. Cops would chase after them. It was hilarious!”

Describing the garden, he said, “Every year it would be the colors of the rainbow coming out. In the middle was the purple, and this was the green circle,” he said, pointing to one of the rings. “Do people know these things? Maybe someone should write a book.”

Friedman added that, to get other tenements around him torn down, so that he could expand the garden, Purple had Friedman’s student friends from Stuyvesant sign petitions to the city saying that the buildings were filled with drug dealers — which was probably true.

Daniel Bowman Simon has posted Purple’s book, “Life with les(s) ego,” online. It’s more of a scrapbook of Purple’s writings, along with newspaper articles about him and the Garden of Eden and even his college report card, sporting mostly “A” ’s. Also included are letters of support for the garden from the likes of poet Allen Ginsberg, former Cultural Affairs Commissioner Bess Myerson and renowned architect James Polshek.

“It offers practical benefits to the people of the Lower East Side: beauty in a bleak place, communal harmony, something the neighborhood cares for, even a little food,” Ginsberg wrote about the garden to Mayor Ed Koch in October 1984. “It is a humane development in the city. In architectural and economic terms, it seems The Garden can be preserved. Please consider all this and communicate your sentiments to the necessary agencies.”

Simon found a copy of the book in The New School’s library and has posted it at 596acres.org.

Outside the memorial event at the garden, purple footprints led down the sidewalk along Avenue C to the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS) one block away, where a “Purple Pop-Up Show” — recently extended — is being held.

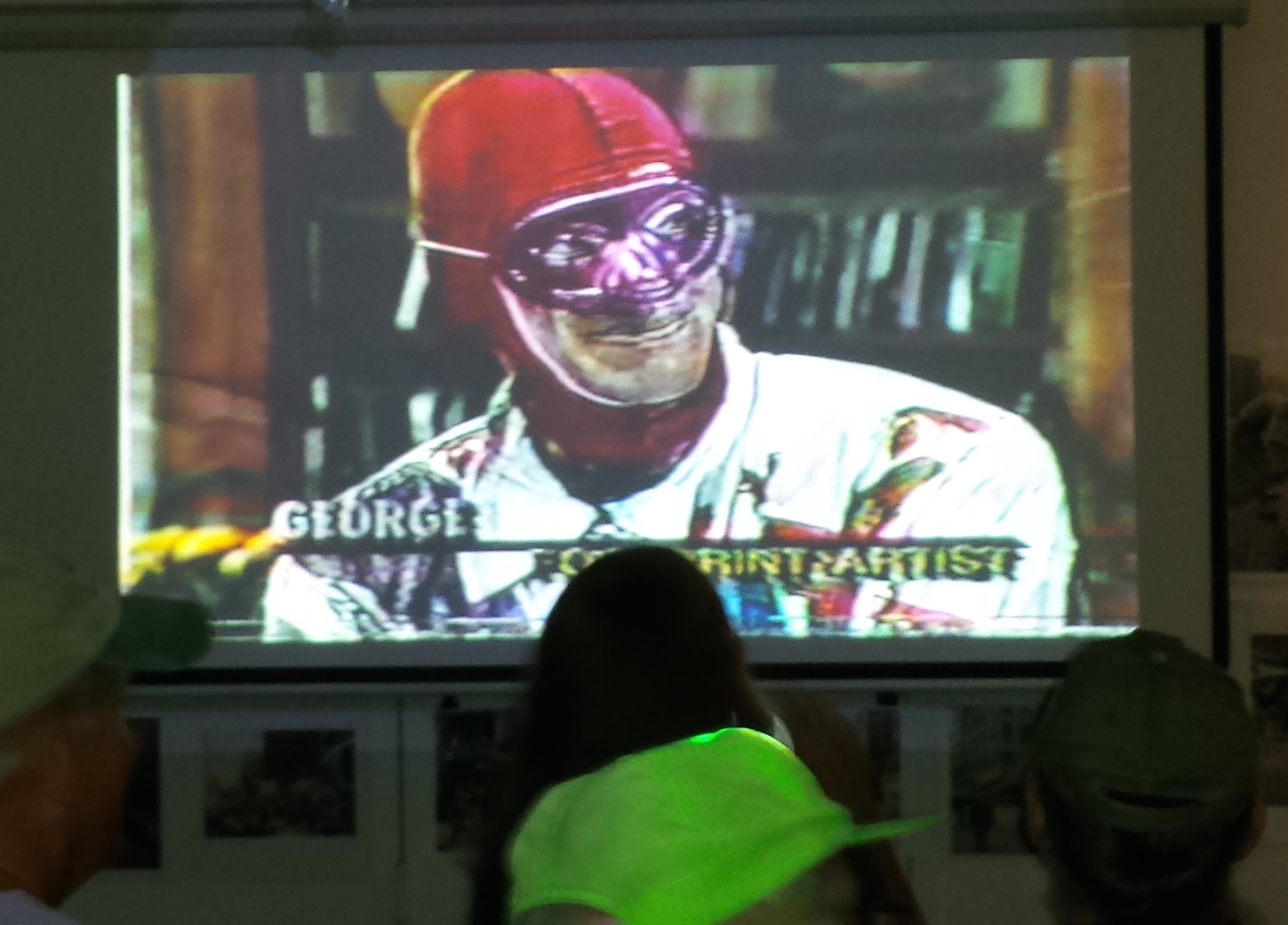

Watching vintage video of Purple at MoRUS was George Bliss, who, in the 1980s, to raise awareness about the embattled garden, laid down 40 miles of purple footprints around the city leading back to Forsyth St.

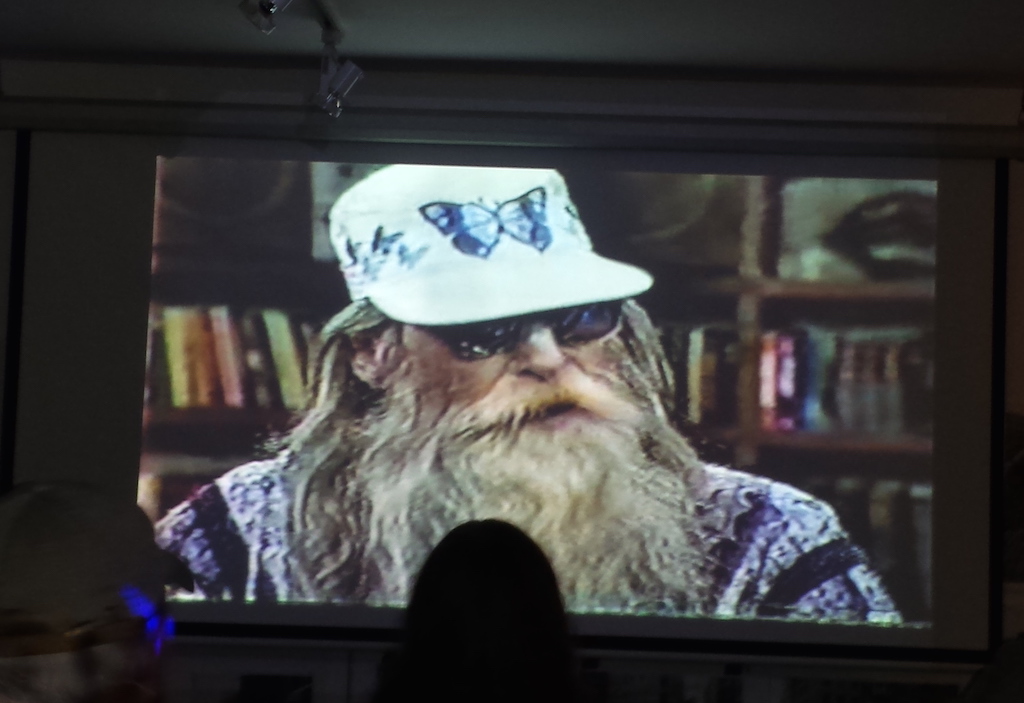

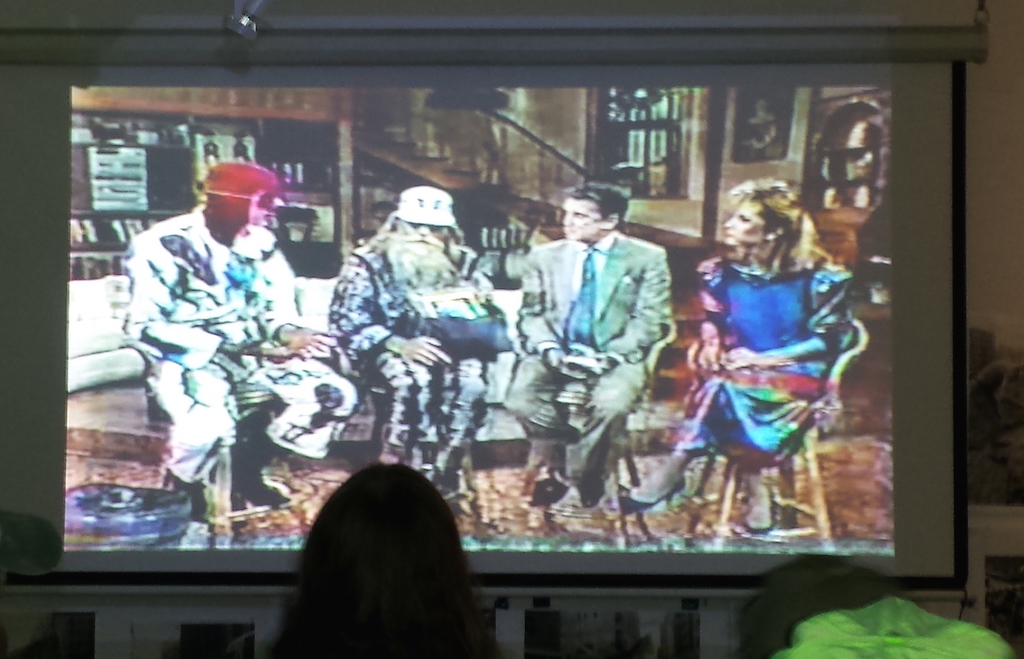

Among the videos was one of Purple and Bliss being interviewed by Regis and Kathie Lee, with Regis in his clipped tones trying to get to the bottom of the housing vs. garden conflict.

“Because it was circular, it posed a threat,” Purple explained. “The birds, bees and insects came back.”

Another video showed Purple busily trundling a wheelbarrow up and down ramps in a rubble-cleared space in the growing garden, and burning wood in a fire to create potash, to add to the new soil.

“Incredible. I’ve never seen this,” Bliss marveled.

As for the footprints, the original machine he used to make them — a drum barrel with foot-shaped sponges, behind which Bliss drilled out holes — sat on display in a corner of the museum. Bliss would foray out at 3 a.m. with the barrel hidden inside a shopping cart that he would roll along the sidewalk. An earlier prototype — tubes running down the inside of his pant legs — was a bust, because the purple paint would create a puddle when he had to wait for the light at crosswalks.

Even after the garden was gone, Bliss doggedly continued plastering the city with the footprints.

“After the destruction,” he said, “I was even more determined to have the media cover it, as a way to force them to tell the story.”