BY YANNIC RACK | A bill currently under consideration by the City Council could soon overhaul New York’s landmarks designation process — and potentially hand some historic buildings to developers, according to opponents.

Intro. 775 — which has been the focus of intense concern amid advocates’ calls to stop it from becoming law — would establish time limits for buildings and districts under consideration by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The measure’s sponsors in the Council say that they intend to clear L.P.C.’s backlog of buildings that are under consideration for designation. The list currently has 95 items, some of which have languished on the commission’s calendar for decades.

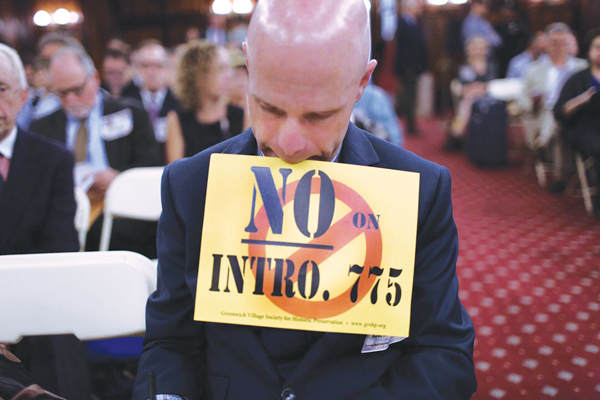

But scores of angry residents and preservationists from across the city crammed into the City Council chambers at City Hall last Wed., Sept. 9, to protest the bill at a hearing of the Land Use Committee.

“The battle is on out there. They’re really coming for us,” said Reno Dakota, who used to live in the East Village and is now a homeowner in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

He was one of dozens of spectators who had come armed with stickers and placards proclaiming “No on Intro. 775.” A badge on his shirt read, “Designate Stuyvesant East” and “Stuyvesant East Preservation Action League.”

The bill’s 10 co-sponsors, among them David Greenfield, chairperson of the Land Use Committee, and Peter Koo, chairperson of the Landmarks Subcommittee, say they only want to increase transparency and bring good government to the landmarks designation process.

“I know there are many differences in this room,” Koo said at the hearing. “But the landmarks process in this city needs to be reformed.”

Under the plans, the commission would have one year to designate individual landmarks, with a public hearing scheduled within half a year after calendaring the landmark for consideration. For historic districts, the time frame would be two years, with a hearing after one year at the latest.

If, under the legislation, L.P.C. disapproved or failed to designate an item, that property would be ineligible for reconsideration of landmark status for five years, during which time there would be no additional restrictions on its owner.

Currently, the commission can place any building on its calendar, without a time limit. Calendaring indicates that the agency is considering a property for designation as a landmark or as part of a historic district. While a property is calendared, the owner, in turn, must go through additional approvals from the city if he wants to alter or demolish it.

Speaking after the hearing, Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation, said the proposed law is a grave threat to eligible buildings.

“It basically gives a green light to any developer to go ahead and demolish a building, simply on the basis of it not having met some artificially imposed deadline,” he said.

“They’ve never even tried [a less restrictive option],” he added. “They’re going from zero to 90 here on this proposal.”

Some of the politicians at the hearing agreed.

“Intro. 775 does not resolve the problem it seeks to address,” said Councilmember Ben Kallos, who is a member of the Landmarks Subcommittee and opposes the bill, adding that it would “lay waste” to communities.

Unsurprisingly, real estate leaders like this legislation.

“The problem is it’s open-ended and indefinite if your building is calendared,” Michael Slattery, the senior vice president for research at the Real Estate Board of New York, an industry group, told The New York Times earlier this month. “If you want to sell your building or develop it, it makes that very hard. Property owners deserve to know what is in their future.”

Meenakshi Srinivasan, who has been L.P.C. chairperson of since last year, was the first to testify at the hearing. She argued against the bill, calling it “far too broad,” and said the City Council should instead let the commission improve its designation process through internal policy changes.

“We believe the proposals are unworkable and would undermine the landmarks law,” she said. “We support the underlying goals, but we believe they are best addressed internally.”

Srinivasan said that once time frames are instituted, the agency’s commissioners would strive to deal with the proposed designations within the allotted time, making the five-year waiting provision unnecessary.

As for the backlog, she said the agency was already addressing that issue. The bill would require L.P.C. to determine whether to designate items currently on the calendar within 18 months of the bill going into law. But L.P.C.’s Web site currently details a plan that would see all these properties dealt with by the end of next year.

Three of the backlogged buildings are in The Villager’s coverage area, according to L.P.C.’s Web site. A wood-framed row house on Sullivan St. in Soho has been calendared since at least 1970. A decision on a Federal-style row house on Second Ave. in the East Village has been pending since 2009. The third is one of the oldest on the list — a five-story building at 801-807 Broadway at the corner of E. 11th St., which has been “under consideration” since 1966. “The Cast Iron Building,” as it’s sometimes called, used to house the James McCreery & Co. Dry Goods emporium when it was built in 1868.

Many point out that the 95 backlogged items only represent a fraction, 0.3 percent, of all the buildings considered for landmarking in New York City ever since the Landmarks Law was passed in 1965.

Critics also argue that, had the bill been in effect in the past, many of the city’s most beloved buildings, like Grand Central Terminal or even Rockefeller Center, could now be history.

“It’s, at worst, a tiny problem that is now being resolved, compared to the huge problem the bill would create if it was enacted,” Berman said, referring to the current backlog.

Greenfield, the Land Use Committee chairperson, seemed at least open to making adjustments to the bill and the length of the time limits, which Srinivasan wants to see extended.

At the hearing a second bill was also discussed. Intro. 837, authored by Councilmember Daniel Garodnick, would mandate that L.P.C. publish a database of all properties already designated as landmarks or historic districts or under consideration for designation.

Srinivasan said the commission would need additional staff to fulfill this “burdensome” requirement, and that the commission is already working on achieving more transparency. Garodnick said the Council committee was working on refining the bill, so that only items requested by community boards would need to be published, for example.

Both bills now seem likely to be changed substantially before the Land Use Committee actually votes on them.

Greenfield mentioned repeatedly during the hearing that his efforts to impose stricter rules on L.P.C. were not motivated by mistrust in its leadership. In fact, he saluted Srinivasan for her work. Yet he remarked that there was no guarantee that future commission chairpersons would be as effective and responsible.

“No agency likes when legislature does their job, which is to actually write legislation,” Greenfield said. “The reality is that, for the last 50 years, we have not had an L.P.C. that is following the rules and regulations, and trying to get every item done in an efficient manner. The challenge that we have is that you, like every chairperson, will probably not serve forever. And therefore we cannot simply rely on your good graces to get the reforms that we want.”