BY NORMAN BORDEN | South African photographer Pieter Hugo’s newest book, unlike his others, is intensely personal. “Kin” is about family and about country and Hugo’s relationship with both.

Photographed over the last eight years, Hugo calls this collection of color portraits, still lifes, cityscapes, and landscapes “an engagement with the failure of the South African colonial experiment and my sense of being colonial driftwood.” He says, “South Africa is such a fractured, schizophrenic, wounded and problematic place…how do you raise a family in such a conflicted society? Before getting married and having children, these questions did not trouble me, now they are more confusing.”

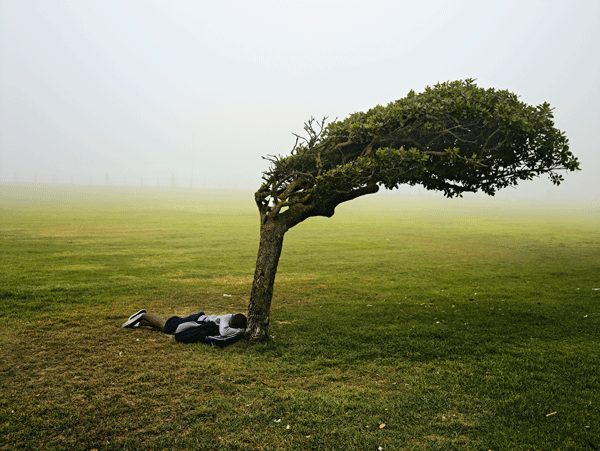

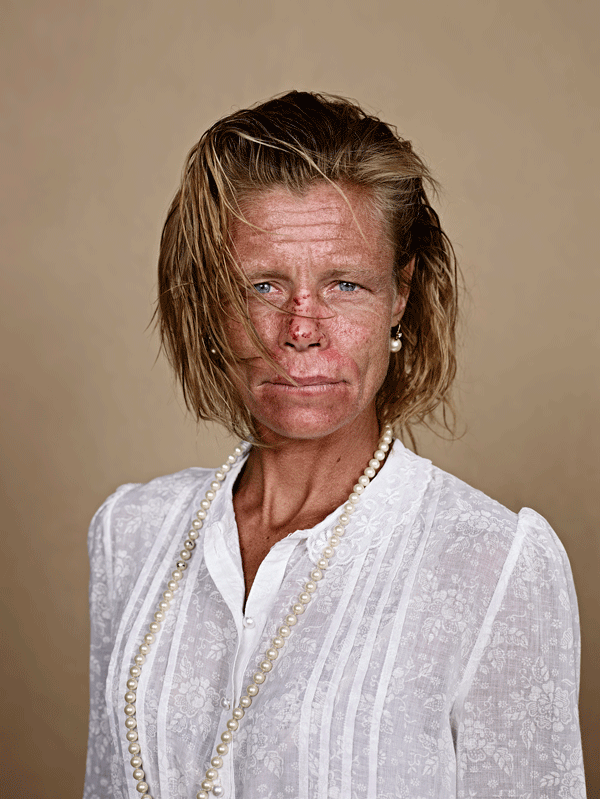

Searching for answers, he begins by photographing what he considers “home” as both an intimate and public place. Hugo does not shrink from showing intimate pictures of his immediate family alongside those of his “kin” which include the homeless, the aimless, the elderly, a racially mixed couple, and others he felt were part of the overall narrative. Other telling photographs include a still life of a dead or dying houseplant and one entitled “Green Point Commons,” which shows a man lying near a huge tree that’s been bent over by the wind — it looks like it’s crying.

Hugo’s photographs of his family show all but tell little. In the photograph of his nude wife entitled “Tamara Reynolds pregnant with our first child,” you wonder why this mother-to-be isn’t smiling or more radiant. He photographs his parents lying in bed, and in another image, we see his mother in bed recovering from her breast reduction surgery. I wonder how he felt taking that?

Hugo doesn’t reveal much of himself either in his 2010 semi-nude self-portrait with his infant daughter Sophia (except for the tattoos on his chest and leg). I do like the casual pose of his bent leg on the bed, but his baby lying in front of his groin looks uncomfortable. His 2014 self-portrait with his new son, Jakob, has a more hopeful air. Hugo rounds out his family album with a portrait of a black woman captioned “Ann Sallies who worked for my parents and helped raise me and my siblings.”

By interspersing his family’s photographs with others from his community, Hugo provides a picture of contemporary South Africa that few outsiders could ever experience.

Hugo tells it as he sees it, using a variety of imagery to document the complex challenges facing his country: its growing income inequality and history of racial segregation, its crowded cities and economic hardships. He alternates pictures of barren landscapes with well-tended gardens, abandoned mining areas with crammed cities, and the affluent with the poor. His country’s painful history is referenced with images of “The Miners’ Monument, Braamfontein” and the bas-relief entitled “The Voortrekker Monument” (The Voortrekkers were Afrikaners who helped to colonize South Africa in the 1830s and 40s).

In “Kin,” Hugo portrays his homeland as a country facing an uncertain future — and many of his images support his thesis. He has created a powerful, engaging look at the rips in its society and they help you understand the mixed feelings he has about being there. The book ends with an image of a dark, moody sunrise — not a pretty picture in my view, but perhaps a telling one.

Photographs by Pieter Hugo, short story by Ben Okri. Published by Aperture Foundation. $75.00. Visit aperture.org and Aperture Gallery and Bookstore (547 W. 27th St. Fourth Fl. btw. 10th & 11th Aves.).

Norman Borden is a New York-based writer and photographer. The author of more than 100 reviews for NYPhotoReview.com, he is a member of Soho Photo Gallery and ASMP. Visit normanbordenphoto.com.