BY NORMAN BORDEN | “Kill City” is literally the inside story about a group of people — mostly teenagers and twentysomethings — who needed a place to live and created a community of “squats” on the Lower East Side.

When photographer and School of Visual Arts student Ash Thayer found herself on the verge of being homeless in 1992, she was welcomed into one of the squats as a guest. She would spend the next seven years living in several different buildings, documenting the realities, challenges and joys of a counterculture existence.

Squatting — the occupying of an abandoned or unoccupied building or area of property that the squatter doesn’t own, rent or have lawful permission to use — is, in part, a response to the lack of affordable housing. That was certainly the case during New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis, when desperate landlords who couldn’t refinance their property abandoned or burned down their buildings for a shot at the insurance money. The city seized these properties due to unpaid taxes, warehoused them and left them to rot. As the numbers of abandoned buildings grew, so did the homeless population.

In the mid-1980s, squatters, which included groups of punk kids, saw the opportunity to reclaim about 30 of these buildings that had been ignored for 15 years. They broke into empty, city-owned buildings located east of Avenue B and began to clean up the insides, patched holes in roofs and ceilings, installed staircases, put up inside walls and called it “home.” They knew it could be temporary because they were trespassing and the cops could evict them at any time. What they also created was a sense of community — working together to improve their quality of life and becoming politically active to effect change.

Living an alternative lifestyle wasn’t an all-new experience for Thayer. Growing up in Memphis, she’d been bullied in high school and left home before graduation to move in with a bunch of punk rock girls. She says, “I shared a room and a single bed and learned about DIY [do-it-yourself] culture, anarchism, atheism, straight-edge, and hardcore.” Being part of the punk community taught her that she could do something with all the pain and rage she was experiencing by turning it into social activism, music, and artistic expression.

So when Thayer moved into See Squat, she felt comfortable in her new surroundings — but as she would learn, living the squatter’s life had its own set of rules. “If you moved into a building as a guest,” she recalls, “you wouldn’t get your own room at first. You would stay and work and earn people’s trust. If you proved you would be an asset to the building instead of sitting in a corner doing drugs or drinking and not doing anything, then you would earn your own room. But the first step was earning a key to the front door. That’s the process I went through.”

Thayer explains that until a building was renovated enough to satisfy NYC’s construction codes, no outsiders could enter. She says, “Some people did drugs, but if they didn’t do their share of the work, they’d get kicked out.” And there was a lot of work to do. Her first building, See Squat, had no plumbing, limited electricity and no heat. “Depending on the building you were in, to prepare for winter you would insulate or sheetrock your room. If there was electricity, you would use it for a space heater or hot plate.”

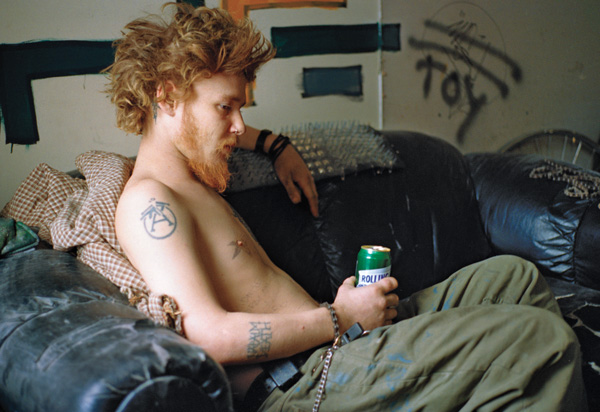

After Thayer moved to Fifth Street Squat and then to one called Serenity House, she began documenting the residents’ daily lives in a way that no outsider could have captured. For example, in the image “Ryan on Couch (Toy), Fifth Street Squat, 1995,” a bare-chested, tattooed Ryan is sitting on his couch holding a can of Rolling Rock, oblivious to the camera, the word “Toy” is scrawled on the wall behind him; the golden light of the afternoon sun illuminates his hair and upper body. It’s a moment of intimacy — Ryan has nothing to hide.

“Jen on Bed, Fifth Street Squat, 1995” is another strong portrait. Jen, with ear, nose and lip rings, looks directly at the camera, projecting the trust she has in the photographer. Other photos — the book contains 116 color and 30 black and white images — offer a window into what daily life was like: backyard barbecues, punk rock parties in the basement, relationships, children playing, and different perspectives of people rebuilding their apartments.

In fact, “Famous, Pregnant and Building Windows, Seventh Street Squat, 1994” is one of Thayer’s favorite images. Famous is wearing a bra and a big tool belt strapped under her large baby bump and doing her share of the work. The photographer considers this an iconic image of feminism that continues to inspire her. She says, “This was very empowering, considering that the 1990s was the decade of the supermodel and unhealthy, unrealistic projections of womanhood.”

Another favorite of hers is “Meggin and Jill Dancing, Fifth Street Squat, 1996” since it exemplified the community of women that Thayer said she needed around her. Another aspect of the squatter’s life appears on a number of successive pages — photographs of street protests in Tompkins Square Park against eviction, and NYC cops in riot helmets lined up and ready to break down the doors.

As insightful and intimate as they are, Thayer’s photographs alone can’t tell the whole story of “Kill City.” Her heartfelt prologue certainly helps you understand the historical context, as does the introduction by Reverend Frank Morales, a squatting pioneer and housing activist. So do a number of brief essays throughout the book that offer varying perspectives on life inside and the real threat outside — eviction. (The threat and protests ended in 2002 when NYC allowed about a dozen of the rebuilt Lower East Side buildings to become co-ops.)

Thayer says the most satisfying aspect of this experience was having a supportive community and living life together. “I loved watching people build their homes. We were poor, but we weren’t lazy.” Over the years, Thayer stayed in touch with some of the people. They became environmentalists, human rights activists, social workers, and acupuncturists. They have families, some have farms. One person is creating communal living spaces upstate. And some of them helped her get “Kill City” published. They told her to get in touch with an editor at the New York Times, which published some of the images online. That got the attention of Powerhouse Books and the rest, as they say, is history — and a story worth telling.

Norman Borden is a New York-based writer and photographer. The author of more than 100 reviews for NYPhotoReview.com, he is a member of Soho Photo Gallery and ASMP, and currently has work on display in Denver’s “Month of Photography” exhibition. Visit normanbordenphoto.com.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Kill City

Lower East Side Squatters

1992-2000

By Ash Thayer

Hardcover, 9-1/4 x 12 inches,

176 pages, $50

powerHouseBooks.com