BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Residents living near Nike’s Zoom City Arena say they’ve been slam-dunked for more than a month by construction noise and diesel fumes, and it’s left them reeling. The spacious structure, they charge, is a flagrant foul against their neighborhood’s quality of life.

Construction on the temporary tent — actually, reportedly two tents — began in early January on the Trinity Real Estate-owned vacant lot at Duarte Square, at Canal St. and Sixth Ave., and only just finished.

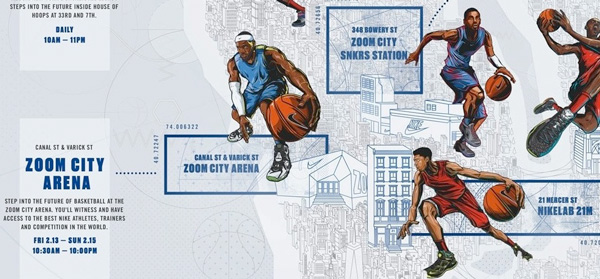

Sporting a snazzy basketball court inside, it’s one of Nike’s key locations for Zoom City, its sneaker sales-centric series of promotions and events tying in with the NBA All-Star Game week, culminating in the big game on Sun., Feb. 15. Zoom City events will kick off midweek.

Top pro players — though, apparently only those with Nike sneaker endorsements — will make the rounds of the Zoom City sites, including the Hudson Square arena, Downtown’s ground zero of All-Star week hype.

Eighteen of the 26 All-Stars have inked Nike sneaker deals, including the likes of LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Pau Gasol, James Harden, Kyrie Irving, Carmelo Anthony, Paul Millsap and Russell Westbrook.

A “Zoom City Map” of events shows an illustration of a superhero-like LeBron dribbling by the Zoom City Arena, so it would be surprising if “King James” doesn’t drop in at some point.

Local high school players and others reportedly will get to meet the superstars.

The main days will be Friday through Sunday, when the tent will see action each day from 10:30 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Zoom City is actually also the name of a line of five new sneakers the multinational sports-shoe giant is launching around the All-Star Game.

As one construction worker outside the Canal St. tent last Friday put it bluntly: “This whole thing is gonna be one f—–billboard.”

But for residents living in 80 Varick St., a 10-story, 61-unit converted former printing building just north of the Zoom tent, it’s been déjà vu all over again. And not in a good way like a “three-peat” — more like being forced to watch the Knicks suffer through yet another abysmal season.

That’s because this is the third time in barely more than a year that the privately owned Canal St. lot has seen noisy construction to create a temporary complex.

To “go to the videotape,” in October and November 2013, the lot was used for another temporary tent for the Talking Transition event, at which advocates and everyday New Yorkers weighed in with suggestions for incoming Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration.

Then, this past August and September, the Trinity lot was again the site of hammer and hacksaw noise followed by hoopla, this time for a Nike tennis extravaganza. Andrei Agassi and Maria Sharapova — both natty in Nike duds — briefly came by to whack balls on a temporary court.

Darlene Lutz, a fine-art adviser, has lived for 35 years in a fourth-floor apartment on the south side of 80 Varick St. — which now directly overlooks the Zoom zone.

“This is a runaway train at this point. It’s the third time,” she said. “We’re getting hammered. Trinity received a rezoning almost two years ago. But they’re not making any great strides to develop that lot.”

Lutz was referring to the Hudson Square rezoning, spearheaded by Trinity, which is intended to increase residential use in the former Printing District. With the rezoning, Trinity announced plans to build a high-rise residential tower in Duarte Square that would include a new public elementary school in its base.

Since then, though, the only work done has been putting up and taking down the mammoth temporary tents.

“The machines they use, they go, ‘beep! beep! beep!’ ” Lutz complained. “There’s a cacophony of them, 15 of them from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

“Their after-hours variances have been revoked twice. They were working 24 hours,” she added.

“The tear-down is as bad as the build-up,” she said, “because all the beeping machines come back. … It took them four weeks to take down Talking Transition — with the beeping and the trucks.”

Meanwhile, jumbo generators occupy a parking lane on Varick St., humming — and spewing diesel pollutants — round the clock to keep the Zoom electricity flowing.

“We can’t breathe,” Lutz said.

Of course, Hudson Square is already deluged daily by the Holland Tunnel traffic’s toxic spew.

“This is an official hot spot, the hottest spot for air pollution in the whole city — and then they add this?” she asked incredulously.

To cope, Lutz, who is a cancer survivor, has taken a room at the James Hotel, across Sixth Ave., and retreats there when the din and air quality get too bad.

Then this past Monday at 8 a.m., the tent’s sound system suddenly cranked all the way up. Lutz called the police, and the sound dropped for a while, before revving up again a few hours later.

“They now have the sound system on,” she said. “It’s like I have a nightclub underneath me.”

As for the actual music, she said, it was “booming rappish-techo stuff — with a lot of bass. It’s like living in a Brooklyn beat party.”

Lutz said she wished activist Don MacPherson, who also lived in 80 Varick, was around to help zing the Zoom City Arena. But he pleaded guilty in 2011 to being part of a massive Hamptons mortgage fraud ring.

“I liked Don. He was on the community board,” Lutz said wistfully. “He’s in prison.”

Others she knows who have been particularly affected by the project, she said, include around 10 dog owners — whose daily routines and walkways have been disrupted — and a model/actress and her boyfriend, who is a music producer with a recording studio in the building, who is having difficulty working due to the racket.

David Webber, one of the dog owners, has had two “confrontations” with the project’s out-of-state security workers. They have been parking their vehicles on a disused part of Sullivan St. that runs through Duarte Square, but which, Webber stressed, is not Trinity-owned property.

“All their license plates are from Georgia,” the British native said. “I had two guys driving like Starsky and Hutch across the bricks of Duarte Square toward me.”

Another security worker accused him of trying to steal equipment.

“I was confronted by a big angry redneck who told me, ‘I’m going to put a beating on you,’ ” he said.

But Webber’s dogs are 140-pound Newfoundlands. While one is a mellow, retired therapy dog, the other growled menacingly at the tough-guy security men, and they scurried back inside their cars.

“My issue,” Webber said, “is I want to walk my dogs on city property without being B.S.’d that it’s private property.”

As for the tent project’s noise and impact, Webber said, “It’s massive in every regard. It’s gotten crazy now that they’re doing sound check. My apartment faces west, so I get the echo. There is a generator issue at night: It’s like having buses idle outside your window all night.”

He works at home as a fashion photographer, and the Zoom zaniness is making him tired and irritable, affecting his job.

“It’s not good when I start yelling at models,” he said.

What particularly galls Lutz and her neighbors, she said, and what initially allowed the tent work to go on round-the-clock was that the application claimed no residents lived nearby — when, in fact, 80 Varick is right across Grand St. from it. Yet, ironically, in 2011, when Occupy Wall Street activists begged Trinity to let them pitch their tents in the lot — after they were evicted from Zuccotti Park — Trinity cited 80 Varick St. in saying no.

“Trinity knows we exist,” Lutz said. “They used as the excuse that it would be an impingement on neighbors’ quality of life — Occupy Wall Street couldn’t come up here.”

But Lutz would gladly take Occupy over Zoom City Arena.

“I’m like, ‘Give me a drum circle over these generators any day,’ ” she said.

Tobi Bergman, chairperson of Community Board 2, said one problem is that the Department of Buildings blithely gives out special work permits.

“Routine provision of after-hours permits by D.O.B. is a longstanding problem,” he said. “These are supposed to be given for the purpose of protecting public safety.

“I know Councilmember Corey Johnson has raised this with the D.O.B. borough commissioner,” Bergman added. “Often, the problem is false information provided to D.O.B. on the application.

“In this case, a late start and bad weather meant some after-hours work had to be done to get the job done before the event begins,” Bergman explained. “The contractor did cooperate by agreeing to stop nighttime work while catching up on the weekends. They also brought in quieter equipment. The setup is now complete. Takedown begins next week and we have been promised it will not include use of noisy equipment after 7 p.m. and that the only weekend work will be while the tent is still up. We’ll see.”

But Bergman added that the lot’s owner, Trinity, needs to step up its diagramming of “X” ’s and “O” ’s beforehand for neighbors about its game plans for the property’s usage.

“Trinity Real Estate’s failure to coordinate the events at this site with the community has been a disappointment,” he said. “It would not be so hard to reach out to the community board and neighbors, and to allow sufficient time for setup so work can get done during regular hours.”

A bigger issue, though, he said, is the lack of movement on the high-rise residential tower — and along with it, the community amenities, including the school, a gym and a public park, that the project would include.

“Trinity’s failure to start construction of the building here is an even greater disappointment,” said Bergman, who lives a block and a half away from the site. “During the Hudson Square rezoning process, we were promised that this would be the first Hudson Square project. It’s important because the community is waiting for the promised new school and new park.”

Bob Gormley, C.B. 2 district manager, added, “D.O.B. is paying attention on this. [Nike] was originally given a 24/7 after-hours variance, which was based on some incorrect information from the applicant, which said there was no one living within 200 feet, which was wrong.”

Normally, permitted hours for construction are 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., he noted.

Then, after the 24/7 permit was pulled, the applicant, a promotion company, pulled another fast one.

“They were given a variance to work from 9 a.m. till 10 p.m. on weekends,” Gormley said. “We were not aware of this.”

In response, D.O.B. ultimately wound up barring work from being done at the site on two weekends, Gormley said.

Moving forward, the agency has ordered that on weekends, outdoor work at Zoom City Arena must end at 7 p.m., meaning no beeping backhoes moving around or beeping lifts going up and down.

At the same time, Gormley added, it was important to get the tent erected in time for this week’s scheduled programs.

“They’ve got to put this up, it’s a big event,” he said. “They’re going to have basketball games and NBA players come talk to the kids.”

As for Trinity, a spokesperson, in a brief statement, said, “The development of Duarte Square is an active and high priority for Trinity. The production company for this event contractually agreed to follow all city regulations, rules and protocols.”

Asked for his take — since Zoom City, at the end of the day, is about scoring sneaker sales — Reverend Billy, the anti-consumer performance-artist preacher, reflected back on Occupy Wall Street and also on the city’s current plan to develop affordable housing on 17 community gardens in Brooklyn and the Bronx. Tuesday morning he had been at rally to save those gardens.

“I remember trying to use that empty space to change the world,” he said of the Duarte Square lot, “and using it to sell Nikes is just the opposite of that. The choices that we make about our urban spaces — when we have choices about vacant lots and gardens — shows our values. You can’t use the place for our tent city, but they welcome in this famous sweatshop company.”

As for the long-range view, what about when the Trinity tower gets built, if it ever does? Won’t that construction be far worse than the tents? No, actually not, maintained Lutz.

“It will all be regulated, and they build so quickly now,” she said, adding, “Look how fast they’re putting up the ‘new Flatiron Building’ on Sixth Ave.”

But she won’t be sticking around to make the comparison.

“I’ll sublet my apartment to young people — who don’t spend any time inside,” she said. “Young people can bear anything.”