BY ZACH WILLIAMS | Chelsea resident Lawrence Walmsley began his morning on Wed., Jan. 7, perusing the news on his iPad when he came across what initially appeared to be an old story: There was a shooting in Paris. In another part of the West Side neighborhood, Ingrid Jean-Baptiste received a phone call informing her that two masked gunmen had just stormed the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

Like people across New York City, they were shocked by the coordinated nature of the attack that left 12 people dead that day, they said. As attacks continued in the subsequent days, the underlying motivations behind the carnage emerged as the world learned that the alleged attackers were two French Muslims inspired by religious zealotry. In the pages of Charlie Hebdo, brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi did not see humor in cartoon lampoons of the Prophet Muhammad. They saw a target.

Visual representations of the prophet are forbidden in Islam, but cartoonists Charlie Hebdo did not care. Staff at the magazine have long delighted in printing caricatures of the powerful and the prickly. A predecessor publication was banned by French authorities in 1970 for making fun of the death of Charles de Gaulle.

A 2011 bomb outside the magazine’s office followed the publication of an issue guest edited in jest by Muhammad with a cover reading: “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter.”

Charlie Hebdo’s sometimes crude brand of humor had a niche following among French people, but did not appeal to others. On Jan. 7 the magazine’s style of free expression assumed a significance unimaginable the day before.

“[Charlie Hebdo] was provocative, so I was not a big fan,” said Jean-Baptiste. “However, I knew how I respected the work of the cartoonists. After all, they are artists and I appreciate everyone’s art, whether I like it or not.”

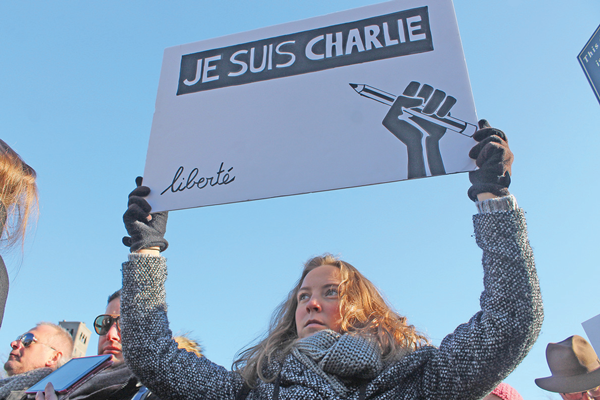

Within hours of the Jan. 7 attack, “Je Suis Charlie” (I am Charlie) emerged from Twitter as the rallying slogan to which millions of people across France and around the world would respond. By the evening in the States, hundreds had gathered in Union Square to express their solidarity with the victims, as well as their shared belief that curtailing free speech was the attackers’ ultimate aim.

As people across the world expressed similar sentiments, the Kouachi brothers remained at large.

They were spotted north of Paris on Jan. 8. But it was in a southern suburb of the city where another man, Amedy Coulibaly fatally shot a police officer and injured another person that day. Hours later, the Kouachis died following a shootout with French law enforcement.

But the killing would continue.

“It was very overwhelming. It just kept going and going,” said Jean-Baptiste, who is co-founder of the Chelsea Film Festival.

She would not learn until Jan. 11 that the father of a friend, Francois-Michel Saada, was among those gunned down by Coulibaly the day before at a kosher market in an eastern neighborhood of Paris. French authorities say there was a link among the three men, according to media reports. Searches continue for remaining suspects.

Twenty people were dead — including the three gunmen — by the time the violence ended on Jan. 9, with 21 others injured in the worst terrorist attack on French soil since 1961.

Thousands of miles from her homeland, Albane de Izaguirre could not find adequate comfort among her American friends. She would find solace among her fellow expatriates at Washington Square Park.

Several hundred people congregated there as millions prepared to march in France over the weekend. They expressed their solidarity mostly through silence with pens and pencils held aloft. Occasionally they would repeat “Je Suis Charlie” in unison, as they held up signs, pencils and pens alike with hands reddened in the frigid air. Some fought back tears as the crowd sang “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem.

“It’s really hard when you’re not in France,” said Raphael Bord, a Williamsburg resident. “You see what’s going on but you cannot really participate.”

Though predominately French nationals and their families, the crowd at the event also included Hell’s Kitchen resident Teresa Cebrian. She said she grew up in Spain amid the fallout from the 2004 Madrid bombing of a commuter train by an Al Qaeda-affiliated group.

Prior to that attack, she had thought that terrorism arising from Islamic extremism was a phenomenom relegated to other countries, she said. Even 10 years later, she said she does not feel safe from the dangers of radical Muslim militants.

“It’s an attack on the freedom of expression in democratic societies and we’ve got to fight against that,” she said of the Paris shootings.

The slaughter evoked memories of the Sept. 11 attacks among many people at the Greenwich Village rally. However, there is a key difference, according to Walmsley and his French wife, Sophie Thumashansen Walmsley. In Paris, the attackers emerged from a “tiny minority” within a native Muslim community living on the edges of French society, whereas the 9/11 hijackers were foreigners.

Muslim immigrants were originally welcomed to France as laborers during more prosperous times. But as one generation gave way to the next, many Muslims in France struggled to assimilate even as second-generation citizens. Recently passed laws forbidding Muslim women from covering their faces in public stoked resentment among them. Radical clerics found a ready audience in recent years among disaffected men, such as the Kouachi brothers, who were children of Algerian immigrants.

French police arrested Cherif in 2005 as he attempted to reach Iraq by way of a Syria-bound flight. Like more than 1,000 Muslim Frenchmen in recent years who have fought in Syria, he wanted to wage jihad, according to media reports. While thwarted in that effort, Cherif eventually achieved his purported goal of achieving martyrdom 10 years later.

Fighting back against such an ideology necessitates a nonviolent approach, said participants of the Jan. 10 Washington Square rally. The attacks represent an opportunity to confront this fringe element of French society, Sophie Thumashansen Walmsley said.

“This could be a rallying cry to get France together again to come up with a new French identity,” she said.

The next day millions of people mobilized across France in similar fashion: toting “Je Suis Charlie” signs, pens and pencils.

Hundreds more came to Lincoln Square Synagogue on W. 68th St. that night to mourn. Among the luminaries in attendance were Chelsea Clinton, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and keynote speaker Senator Chuck Schumer. When the meeting room filled to capacity, 100 more congregated in a hallway. Soon 100 more stood outside in the winter cold vainly hoping for admittance.

As Schumer prepared to speak on U.S. support for France, Jean-Baptiste soon found her own place to mourn. Stuck outside, she joined a dozen others in a quiet Jewish prayer recited from smartphones.

“Right now the only solution is to gather and be united,” she told The Villager earlier that day.

As the new work week began, reports of reprisal attacks against French Muslims continued.

At the same time, police were being deployed around Jewish businesses, schools and other “sensitive sites.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that Israel was ready to accept with “open arms” Jews now fearful of living in France. Last year, amid rising anti-Semitism, a record 7,000 French Jews made aliyah to Israel.

By Tues., Jan. 13, 10,000 soldiers were patrolling neighborhoods throughout the country and French President Francois Hollande had declared war on terrorism.

That same day, Charlie Hebdo staff announced that the Prophet Muhammad would once again grace the cover of their magazine. This time, though, they printed 3 million copies rather than the magazine’s typical circulation of 60,000.

On the magazine’s cover, the caricature totes a sign with the now-famous “Je Suis Charlie” slogan and sheds a tear of contrition.

“Tout est pardonné,” reads the cover. “All is forgiven.”