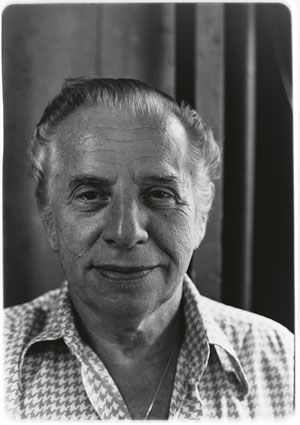

BY NORMAN BORDEN | Chances are the Terminal Bar wasn’t what Frank Sinatra had in mind when he famously sang, “It’s quarter to three, there’s no one in the place except you and me.” Nah, the Terminal Bar was a dump, a real dive and a hell of a watering hole that some called “the roughest bar in town.” Murray Goldman, the bar’s owner since 1956, thought that was media hype — but Martin Scorsese did use it in “Taxi Driver.”

Located across the street from the Port Authority Bus Terminal on the corner of Eighth Avenue and West 41st Street, the bar was where an endless, diverse stream of customers would wander in for a drink and chat it up with the bartender and a rogues gallery of regulars.

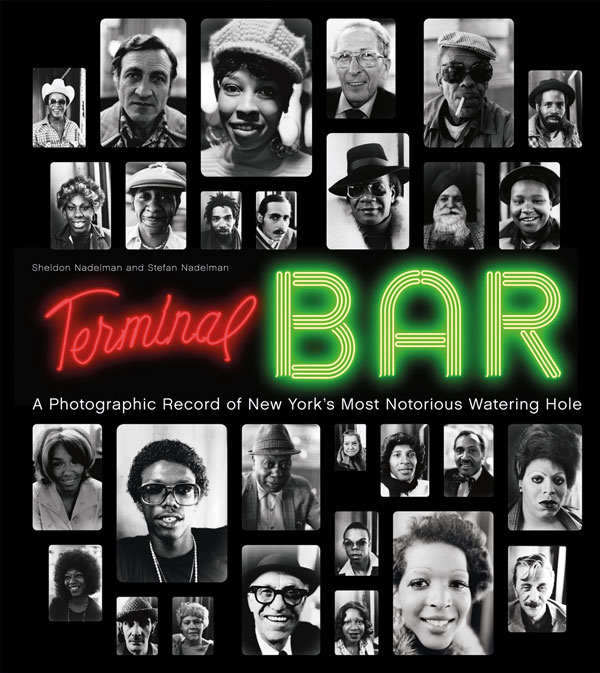

TERMINAL BAR | A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF NEW YORK’S MOST NOTORIOUS WATERING HOLE

BY SHELDON & STEFAN NADELMAN

Princeton Architectural Press

Hardcover | 176 pp. | 8×9 in. | $35

Visit papress.com

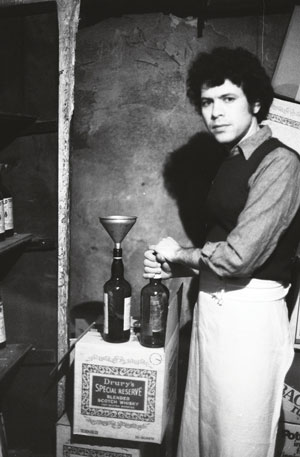

Shelly Nadelman got to know a lot of them during the ten years he spent there as a bartender, from 1972 until its closing. When Goldman (his father-in-law) offered him a bartender’s job to help feed Nadelman’s growing family, he started working the day shift. But he didn’t just serve his customers drinks. He also took their picture — thousands of them.

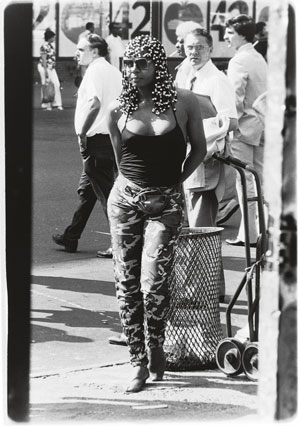

Using his 35mm camera, he shot black and white portraits of the regulars, the locals, the pimps, prostitutes, office workers, commuters, bus drivers, gay men, drag queens, and adventure-seeking tourists. This let him satisfy his passion for photography while still tending bar.

Nadelman’s son, Stefan, says, “My father looked at all new customers as potential portraits. When they walked in he would size them up, imagining them as sixteen-by-twenty-inch prints, and if they met all the necessary criteria, he’d ask if he could take their picture.” He’d develop the roll of film in his darkroom and then make 8×10 inch prints. He hung some on the bar’s walls to promote his work and once in a while, a customer would buy one for five bucks.

Over the years, he took more than 2,600 images that documented a period of New York’s visual and cultural history that has vanished (only 22 were self-portraits). After the bar shut down on January 8, 1982, the Times Square area underwent major changes — sanitized and Disneyfied and corporatized. In fact, the headquarters of the New York Times now occupies the block where the Terminal Bar once was.

When Murray Goldman decided to close the business because of rising rent and decreasing business, his son-in-law went home to New Jersey. His photo archive from the bar would go unseen for 20 years until Stefan began to sort and scan the negatives. He had long recognized their historic significance and featured many of the images in his first film, “The Terminal Bar” — a 22-minute documentary about the bar’s customers. The elder Nadelman plays a key role, recalling details about the cast of New York characters that he served, even remembering their favorite drink.

“The Terminal Bar” went on to win the 2003 Sundance Jury Prize in the short film category, among other honors. Stefan says, “There were several publishers who approached me after the film hit the festival circuit, but these discussions inevitably fizzled out. So the book idea was filed away once again. Over the past decade, I released some more short Terminal Bar films on my YouTube channel that complemented the original.”

These attracted more attention to the original documentary, and in 2013 Stefan got a book offer. He says, “I think the past 12 years helped age the photos a bit more, and that extra distance from the 70s gives the collection more historic value.”

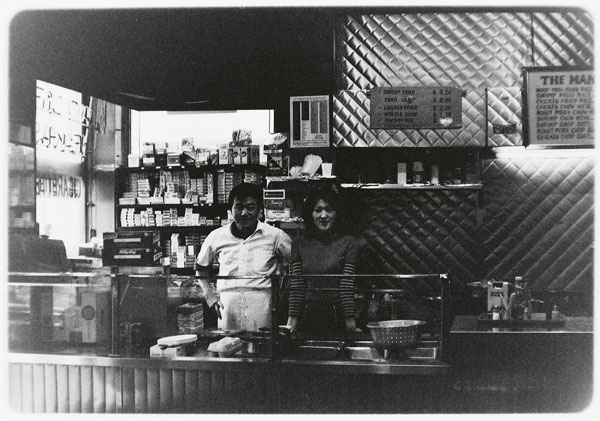

As photography books go, this one may be as unique as its subject. There are no pretty pictures here, no glamour shots. The first few pages set the stage with location shots: the exterior of the bar, the pedestrian traffic, the Port Authority terminal across the street. The rest of the book is filled with headshots and group portraits of customers organized by categories such as “The Regulars,” “Old-Timers,” “The New Wave,” ”One-Shot Opportunities” and “The Place to Be.” Other sections include “Family,” “Bartenders,” “Porters” and “Concession Workers.”

Some of Nadelman’s recollections about his customers are used as captions. Of the “New Wave” gay men and trans people who began to frequent Terminal Bar after the Stonewall riots, Nadelman recalls his 1973-1978 photos of one customer who “used to come in on Saturdays, and the more he drank, the more lipstick he put on. Every time he came in he had another hairdo. I bought one of his Pentax cameras from him: fifty dollars and a telephoto lens. He was also a beer drinker.”

The eight photographs of Larry, a “Regular,” were taken over a seven-year period and end with Larry wearing a gold chain. Clearly, Larry enjoyed having his picture taken. In “The Place to Be” are portraits of couples, friends, and guys just hanging out at the bar after work.

The photograph of the “Merry Christmas” banner over the bar and Joe the porter taking a break gives the place a sense of community…but we know there were few silent nights at the Terminal.

Shelly Nadelman has clearly captured the essence of the Terminal Bar — its tawdriness, sleaziness and, most of all, the faces and idiosyncrasies of the people who posed for him. His pictures are 30 to 40 years old and you wonder where these people are now. But then Nadelman’s observation in his son’s film comes to mind: “The street’s gonna get you, the street’s gonna eat them alive, all these people are gonna disappear…” And yet during the Terminal Bar’s existence, from 1956 to 1982, some of the city’s forgotten people found a home of sorts, a temporary refuge from the streets and the chance to get their picture taken. They won’t disappear. Shelly Nadelman and his son Stefan made sure of that.

Norman Borden is a New York-based writer and photographer. The author of more than 100 reviews for NYPhotoReview.com and a member of Soho Photo Gallery and ASMP, his image “Williamsburg” was chosen by juror Jennifer Blessing, Curator of Photography at the Guggenheim, for inclusion in the upcoming 2014 competition issue of The Photo Review. Seventy of his contemporary photographs are in “Synagogues of New York’s Lower East Side,” which Fordham University Press just reissued as a trade paperback. Visit normanbordenphoto.com.