BY YANNIC RACK | When Joyce Pearlman started teaching kindergarten in the East Village 45 years ago, the neighborhood was, to put it mildly, a little different. It turned out that living in Mt. Vernon and teaching in the Bronx hadn’t quite prepared her for the move to Avenue C and E. 10th St. in 1969.

“The first week I lived here, I opened up my window shades on Sunday — I moved in on Tuesday — and there’s a dead body in the middle of Avenue C!” she recalled. “And then I would see the drug exchanges — it was really Alphabet City.”

“But what saved me, what was really great, was teaching at that school, teaching the neighborhood kids,” she said.

Pearlman lived just a couple of blocks away from P.S. 61, at 610 E. 12th St., her new workplace, in the brand-new Village East Towers, three apartment blocks that were built as part of the state’s Mitchell-Lama Housing Program for middle-income families.

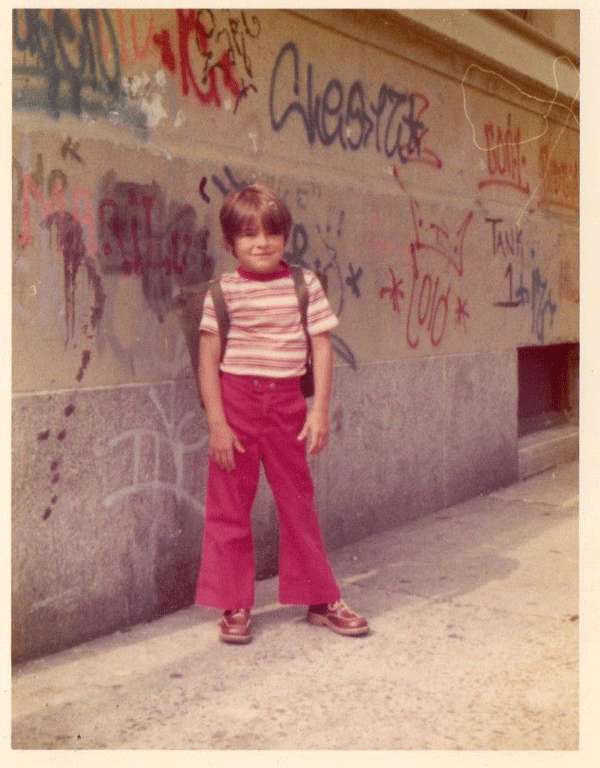

One of the neighborhood kids was Todd Ferrara, who went to P.S. 61, too, although Pearlman said she didn’t teach him. Today, he lives just a few floors up from her apartment, with his wife and two daughters, in the same building he grew up in.

Mitchell-Lama complexes “were mostly built in neighborhoods where nobody wanted to live,” Ferrara said of the building. “You know, this neighborhood, back then, was pretty decrepit. I would say a good 50 percent of the houses were just burned out or abandoned lots or whatever.”

His parents, biology teachers at nearby Stuyvesant High School, were also among the towers’ original occupants. They moved from the 12th to the 20th floor in 1982, Ferrara’s last year at P.S. 61.

Now, more than 30 years later, his older daughter, Julia, was about to start pre-K in his old school building, at the East Village Community School, which goes from pre-K to fifth grade.

She couldn’t attend the same school her dad had, even if she wanted to: The original P.S. 61 was shut down in 1996. At that time, it had already operated as a satellite school, hosting The Children’s Workshop School and The S.P.E.C.T.R.U.M. School, and in 2001 the newly renamed East Village Community School moved into the building.

“I guess, in retrospect, there were some odd things about it that were hallmarks of a troubled inner-city school, but it was not something that we really felt,” Ferrara said of his time there. He is glad his daughter is going to a safer school than he did.

The playground, he remembered, would sometimes be littered with “drug paraphernalia,” especially on Mondays, and it wasn’t uncommon to have glue-sniffing junkies hanging around (adults, not kids), as well as other “unsavory characters.”

And then there was the semester when everybody was buying knives.

“One semester there was this hardware store that decided that selling $5 knives to kids was a great idea,” he recalled. “Everybody had one. I don’t think I did because I knew my parents would kill me. But when the school started finding out about it, the kids would give me the knives at lunch to carry into the school in my backpack. Nobody would suspect me, I was the tiniest kid, the assistant principal lived right downstairs on the 19th floor of this building. … I think there would be more of a community outcry about that sort of thing today.”

At the same time, Ferrara mourns parts of his old turf that are gone, particularly the family-owned grocery stores and the mom-and-pop businesses. He keeps a folder with menus of closed restaurants, artifacts of a changing neighborhood.

“When the 2nd Ave. Deli went, that was a blow,” he said. “When Di Bella [Bros.] went, that was a blow. When the Polish butcher closed, that was a blow. I’m just wishing the hipsters could afford to be here and open their butcher shops and their crazy stuff — you know, pickle stores or whatever — ’cause that’s what I miss!”

Pearlman agreed that the neighborhood around her has transformed, for better or worse.

“Well, in a sense, the neighborhood got safer and it got better, because the crime left, and the drugs,” she said. “Of course now it’s ludicrously expensive. I mean, we’ve lost all the ethnic businesses and the mom-and-pop businesses.”

Another thing that has changed since her early teaching years is education, and not just the curriculum.

“Teachers can’t be like I was, they can’t hug and kiss their kids!” she said. “They can’t be affectionate. Teachers can’t touch a child, it could be child abuse, it could be sexual. They’re afraid to touch kids!”

Some of her methods would be less controversial but still unusual nowadays. For example, when one of the mothers of her students (she affectionately calls them “my moms”) would be running late because of her job, Pearlman said she would simply take the child home and babysit.

“I really became part of their lives, and they became part of mine,” she said. “I still see them now. In fact, two or three kids that were in my kindergarten classes live in my building.”

“I knew the kids, I knew the neighborhood. And I knew what kind of life my kids had in Campos Plaza and the buildings they lived in at the time. I just made sure that my class was the safest place in the world for them. And they wanted to be in school, because they knew I was there for them.”

Pearlman taught at P.S. 61 until 1996, when the school closed after more than 80 years in operation. The building itself just celebrated its 101st anniversary as a school last weekend. An official celebration was actually scheduled for last year’s centennial but had to be pushed back because of construction work.

Since P.S. 61 first opened its doors in 1913, a year after the building was built, the school has witnessed a lot. That’s why, intrigued by a large historical plaque in its auditorium, Jason McDonald started getting interested in the place’s history three years ago.

McDonald teaches history at Grace Church School, at E. 11th St. and Fourth Ave., but has a son at East Village Community School. Over the past two years, he has put together a book about the E. 12th St. school’s history, which will be used to teach children at all three schools that currently use the building.

The book is also a guide through the last century. In it, McDonald describes the neighborhood during both world wars, as well as the effects of the 1950s red scare. He also quotes from a 1952 Life magazine article that profiled the school and its principal, Max Francke.

Back then, some of Francke’s teachers had 50 students in their classes. In fact, the school had 2,011 students in 1,470 authorized seats in October 1952, making it New York City’s most overcrowded school.

Back in 1914, there were 2,550 students enrolled in the building, according to Bradley Goodman, the current principal of East Village Community School. This year, there are barely 600 kids enrolled across all three schools located there.

“I don’t even know how they fit them into the building back then — in the same exact space!” he said.

By the time Ferrara attended the school in the ’70s and ’80s, the overcrowding problem wasn’t so bad anymore. But that doesn’t mean the school had the best reputation. To escape school zoning, he said, many of his peers would give false addresses to attend schools that were considered better than P.S. 61.

“Third grade was sort of the dividing line,” he explained, “when a lot of the kids whose parents had a little more wherewithal to game the system, all figured out that they could find a friend in the West Village or someone else and make up an address and send their kids there.”

Nowadays, according to Principal Goodman, it’s usually the other way around, as the schools in the E. 12th St. building are more sought after.

“We’ve become very popular,” he said. “Now we have families in Brooklyn. I don’t know if they’re faking it, but certainly there’s a much higher demand!”