BY GERARD FLYNN | Although Tompkins Square has kicked its reputation for hardcore heroin use, there’s still junk around if you’re looking, said a member of the park’s transient population recently.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, he said today’s heroin trade, as in past years, is not hard to find.

“They are here right now. I can see them but I’m not going to point them out to you,” he whispered, as he lay across a park bench, his daytime home since losing his job around Christmas.

The 10.5-acre park, he insisted, is not just the site for dealing, but also for routine overdosing.

“Across the street,” he said, gesturing toward the corner of Avenue A and Seventh St., “a young homeless girl died last week, just passed out.”

He then made another point, a local topic of debate ever since actor Philip Seymour Hoffman was found dead with a needle in his arm in February.

Nobody would have known about it had Hoffman not been “white and rich,” he said.

While the former legal clerk knew a lot about the late actor’s thespian skills, he had never heard of naloxone, a prescription drug that reverses an opioid overdose’s effects and might have saved the 46-year-old’s life had the tightly regulated drug been more readily available.

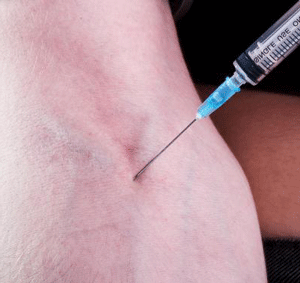

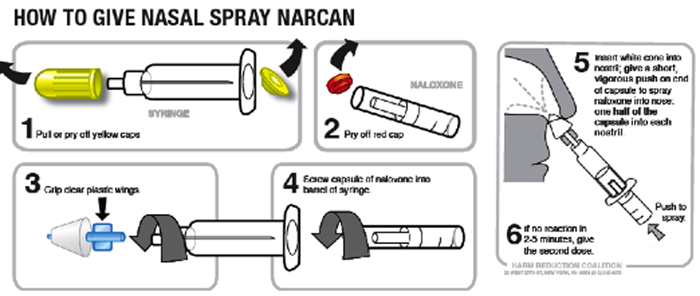

Given intravenously or by nasal spray, Narcan, as it’s known under a trademark name, was recently in the news. In March, the Federal Drug Administration announced the introduction of the antidote’s next incarnation, an auto-inject device called Evzio. The device was fast-tracked by Congress as the opioid-overdose epidemic continues to grip the nation.

It “doesn’t mean s— around here,” the park denizen scoffed, because “once you OD, you’re gone.”

Naloxone works by rapidly blocking opioid receptors, but because its effects wear off within 90 minutes, prompt medical attention is usually required.

Following the news in Washington, this month the state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s Office launched the Community Overdose Prevention, or COP, initiative. COP will enable every state and local law enforcement officer to carry a naloxone kit.

Drug overdose is a leading cause of accidental death in New York City, with the majority of incidents involving either heroin or prescription painkillers. Heroin was involved in 52 percent of all overdose deaths in 2012, a steep rise in recent years after a four-year fall.

Alongside neighborhoods in the Bronx and Staten Island, Union Square and the Lower East Side rank among the city’s top five areas for heroin fatalities. A second party, often Xanax or Valium, is also often found post-mortem.

In addition to heroin’s increased purity, the feds’ crackdown on prescription opioid abuse has been cited as contributing to the city’s heroin crisis, since users switch over from opioid pills to heroin. A recent Health Department report suggests, however, heroin use’s upward trend is happening regardless of federal efforts.

Mirka Feinstein, director of the Lower East Side Drop-In Center, on Essex St., which works with homeless youth and drug users, said local heroin use appears to be stable, though OD’s usually spike every few years.

One such shift occurred early this year, she said, felling up to five people, and involved a fentanyl-based “killer heroin.” A powerful painkiller often used in cancer treatment, fentanyl is a synthetic opiate up to 100 times more powerful than morphine.

Feinstein added that former users who return to their heroin habit are also at increased risk of overdosing, which reportedly played a role in Hoffman’s demise. Their bodies can’t handle the same doses they were used to.

Along with training on how to administer naloxone, police need additional advice on how to get along better with this community, users and service providers alike say.

A local building superintendent, who recalled “back in the days” when junkies would line up by the dozen and get their bags handed to them through a crack in a wall, had not heard about heroin’s comeback.

He laughed as he recalled a neighborhood “infested with heroin” and what an overdose meant in the 1980s. In those days, cops were a bit anxious about coming down to Avenue B to make arrests.

“Back then, if someone OD’d, it was a sign of good heroin,” he said. “All the junkies would go crazy wanting to know where he got his s— from.”