BY GERARD FLYNN | While noisy boozers at McSorley’s Old Ale House were busy Good Friday celebrating none too piously, right across the street at St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church, quieter proceedings were being observed at midday Mass.

Inside the E. Seventh St. church, a solemn procession of robed priests slowly made its way as choral chants swelled. Rows of the devoted stood in their pews as a cloud of incense hung in the air.

Exalted as the language of the sacred proceedings were, outside only profane words were flowing out of the mouths of the observant for none other than the Great Satan himself — Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Despite the festive pre-Easter mood, Ukrainians, what is left of them in the increasingly hip East Village, were doubtful and dour about the international community’s efforts to broker peace between the bordering Eastern European countries. The blame for the crisis, which appears to be ratcheting up once more, rests squarely with the cunning ex-K.G.B. agent, they said.

“Putin can’t be trusted,” one elderly parishioner said bitterly on the church’s steps. His claims for the Russian minority population’s safety in eastern Ukraine mask Putin’s true territorial ambitions for a greater Russia, she said.

Despite peaceful reassurances from the Kremlin, war clouds no doubt are looming, she warned.

As 40,000 Russian soldiers gathered thousands of miles away on Ukraine’s eastern border, outside a nearby meat market on Second Ave., a crowd braved the chill to line up to buy meat for the traditional breakfast on Easter Sunday.

Among them was Mary Reszitnyk, a first-generation Ukrainian-American. With the back of her hand, she pushed aside Russian claims to the eastern region like she was sweeping off Putin’s pieces during a game of Risk.

Russians who live there should see themselves as migrants, not rightful heirs to the land, she declared.

“Just because a lot of Russians went to live there doesn’t mean it’s theirs,” she said. All kinds of migrants come to live in America, she added, but they don’t claim it belongs to the old country. With “too much emotion” in the crowd, however, she predicts “there will be a fight and bloodshed.”

Photos published on news Web sites Tuesday showing what appear to be Russian troops on Ukrainian soil might confirm her worst fears. They only amplified those of Taras Sherchenko, a Ukrainian native who was waiting outside the butcher for her husband with a bunch of groceries.

She has been watching the news every day and frets that “the Communist” will never change and has ambitions that go beyond Russia’s eastern borders.

“I am worried it will happen to the rest of Ukraine,” she said.

Much of the crisis has been driven by Russia’s ire at Ukraine’s attempts to move closer to the European Union, a move Putin has been trying to stop. Scores have been killed in clashes, mostly, pro-independence Ukrainian protesters.

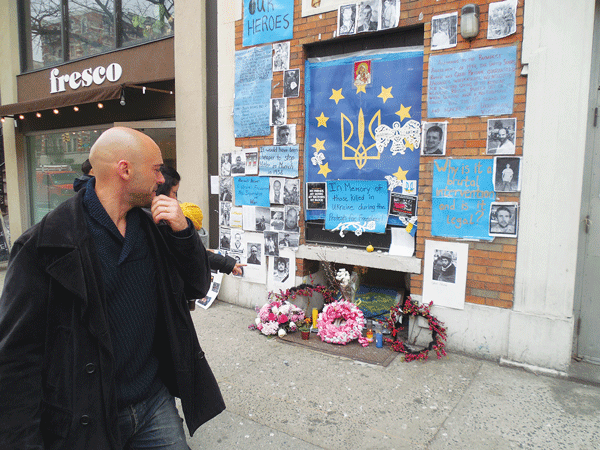

If that indeed is Putin’s plan, Olga Kober, a Ukrainian immigrant, standing across the street from a memorial to her homeland’s dead on Second Ave., said it’s up to the West to stop the Russian strongman. Her people, she said, “want to move west” where there is a “different mentality.”

“Russia is a big liar,” she said, “a very big liar.”

After Easter festivities pass, she said, Putin will return to his schemes, which will, hopefully, amount to “probably nothing — if the U.S. and Europe don’t turn away.”