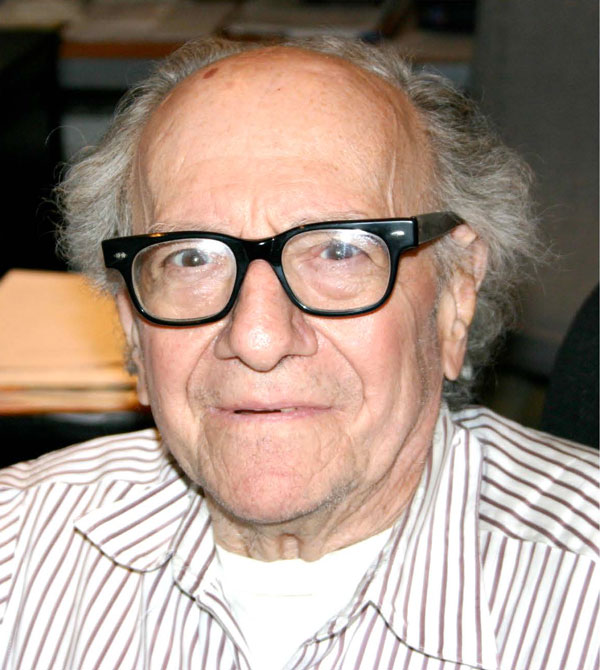

BY JERRY TALLMER | The lunch at the Chinese restaurant on Eighth Street went on for a couple of hours. I liked Dan Wolf the moment I laid eyes on him. He looked like me, slim, dark, average height. And he thought like me, full of political skepticism, not to say sarcasm. I didn’t know this at the time, but Dan was also pretty deaf, which I was not — not then — and he used his deafness whenever a discussion began to bore him or get out of hand.

Neither Ed Fancher nor Dan Wolf had any newspaper or magazine experience whatsoever. My own slender track record was editorship, just before and after World War II, of a pro-interventionist college daily newspaper, The Dartmouth, up in Hanover, New Hampshire, followed by two or three postwar years on a hallowed radical magazine, Freda Kirchwey’s The Nation, where I wasn’t allowed to write anything. That was followed by a few years as a blocked writer living at 265 West 11th Street, during which I spent too much time staring with venom at the pigeons pooping on the cornices of the buildings across the way while I babbled inanely: “Pigeons on the grass, alas… .” What grass? And Bobby Thompson’s home run heard round the world — and by me on a portable radio five flights up in that apartment, where an earlier tenant had been Surrealism’s André Breton.

Ed Fancher, a graduate of the University of Alaska, was the scion of the family that owned the Orange County Telephone Company in Upstate Middletown, New York. He was going to put toward the newspaper some money his grandfather had left him for a trip around the world. Daniel Wolf had no money to speak of. He had written the Turkish section of an encyclopedia. They told me that Dan’s friend Norman Mailer was going to be a silent partner, solely an investor to help them get started. I asked how much money they had, all told, and Ed said, if I remember rightly, $5,000. In my infinite wisdom I leaned back and said: “Well, maybe if you guys had twice that… .”

(In the end, it would take more than $65,000 and a New York City 1962 daily newspaper strike before The Village Voice broke even.)

There, in the Chinese restaurant on Eighth Street, I finally said: “Well, gentlemen, thanks again but no thanks. Maybe, if you actually do get this thing off the ground, if you ever need something like a movie review… .”

And I went out, that day or the next, I forget which, and visited every single movie house — there were then about a dozen — in Greenwich Village. I sought out the manager of each one — movie-theater managers, except for those at a couple of art houses, were not then on the whole a notably agreeable or polite or intellectual breed — and I asked each of them if they could and would supply, in advance, their week’s movie schedules, titles and show times, to a new newspaper in their area. Grouchily, sneeringly or however, they all said they’d do it if it didn’t cost a penny and they didn’t have to do anything more than let us copy the schedules.

I phoned Ed Fancher and told him what had transpired.

“I knew right then that we’d hooked you,” he has told me — told everybody — many times since. And the movie listings — two double columns of type at the very center of the paper, with titles, hours and capsule appraisals, became the heart and spine of The Village Voice from Day One to as long as I was there to fight for that layout.