BY MICHELE HERMAN | It was the fall of 1987. My husband, who was then merely my POSSLQ (Person of Opposite Sex Sharing Living Quarters), and I had moved to the West Village a couple of years earlier and still couldn’t believe our good fortune. So we threw ourselves into neighborhood activities, including a meeting of a small neighborhood preservation group called Save the Village.

This group later got folded into a larger coalition called the Federation to Preserve the Greenwich Village Waterfront. But then it was a little band of activists run by Pearl Broder, a West Village Houses resident who became a lifelong friend.

Pearl had spoken up for many of us who were blindsided when an attention-grabbing, 18-story tower called the Memphis Downtown went up as of right on the corner of Charles and Washington Sts., harbinger of more overdevelopment to come.

My husband and I were the newbies at the meeting. The agenda came around, as agendas often do, to fundraising, and we brainstormed ideas. Somebody said, How about a benefit concert? We set our sights on Suzanne Vega, the indie singer-songwriter who was hot stuff then and who was rumored to live on Horatio St.

Having learned early on in such situations to volunteer for an easy job before someone asked me to do a hard job, I raised my hand and said I would write a letter to Pete Seeger. In those days writing a letter took more effort than it does now. But somehow or other I found his address in Beacon, N.Y., typed a letter on my fancy electric Olympia typewriter, and forgot all about it.

But then Pete wrote back and said he would be happy to do a concert for us. As I recall, my letter never specified the exact cause and he never asked. My husband and I, who had never organized a concert or much of anything else, looked at each other and said, I guess we’re doing a Pete Seeger concert.

Pete’s letter told me to talk to his manager, Harold Leventhal, who would do all the arranging. If you had to make up a crusty old manager in your head, the kind with a cigar and a crammed office up a steep flight of steps in a squalid building somewhere near Broadway, you couldn’t do much better. It was only later I learned that this guy, who I recall being quite unimpressed by me and my youthful enthusiasm, was one of the great champions of American folk music.

It turned out that the hardest part of organizing the concert was getting St. Luke’s, which we had our hearts set on, to let us use the church on a Sunday in January; I recall some serious arm-twisting by a preservationist friend who knew the pastor.

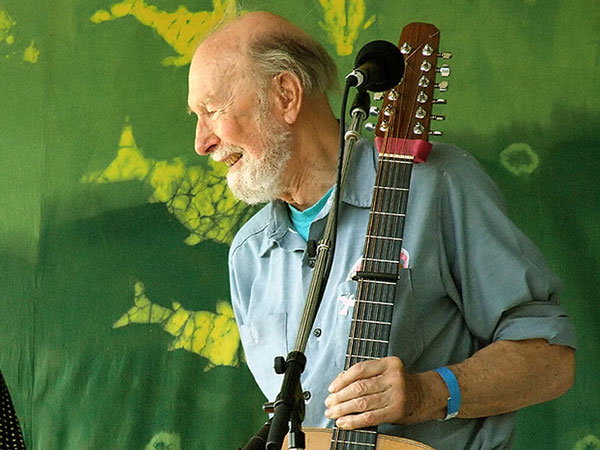

Publicity was a breeze. I went to the Lincoln Center library and leafed through their manila folders of celebrity photos. Pretty much any image of Pete screams “iconic”; I chose him with both hands around the neck of his banjo, looking pensive in a work shirt with the sleeves rolled up.

I designed a flier using my Olympia. For the headline, “Save the Village Presents An Afternoon With Pete Seeger,” I did my own calligraphy. I made a bunch of fliers and bright-yellow postcards. Now and again I still run across one of the postcards in a book I haven’t opened in a while, and I smile at the memory (and at the terrible quality of the third-generation Xerox).

We used our own phone number for the RSVP.

Thanks to our fliers taped up around the neighborhood, we sold out on Friday, just before the Times ran a small notice. Our phone rang pretty much continuously all weekend. We recorded a message that began with Pete singing “Sailing down my golden river” and ended with us saying, sorry, tickets were no longer available.

We kicked ourselves for setting the price so low ($20 for adults and $12 for seniors, kids and students) — we could have sold out Carnegie Hall at $50 a pop.

That concert spoiled me for all subsequent fundraisers and remains my model for how to raise a lot of money without laying a lot of money or effort. I spent about $20 on photocopies. We found a sound guy at the Henry Street Settlement and paid him $150. He thanked us afterward for the privilege. That was the sum of our expenses.

My husband and I aren’t sure, but we think I introduced him, and he introduced Pete. We were both nearly sick with nerves — we understood that Pete was not just a celebrity, but had made enough contributions to civilization to rank among the greats.

It may well be that this concert was the only one Pete performed solo in the Village between the 1960s and his death. All I remember of my introduction is that I was kicking myself when I searched for the word “humanitarian” to go with “causes,” but the only word I could retrieve was “liberal,” which didn’t convey half of the gravitas I wanted.

Neither my husband nor I remember much about that afternoon. I know that I shook Pete’s hand in the vestibule and introduced myself, and that he seemed frail and preoccupied, as a performer has every right to be before performing alone in an unfamiliar venue.

My husband remembers him stunning the audience by noting that the church we were sitting in was built in 1822, five years before slavery was abolished in New York.

I remember a prescient line that I can’t quite reproduce but often mull over, about how we need to find a way for the American economy to remain standing without having to grow ever bigger. I remember that he was funny, and not the least bit sanctimonious.

I think he sang “Abiyoyo.” I know he sang quite a few rounds of “Guantanamera,” and that we all joined in. His voice was already reedy and his range quite limited, but it was one of the most instantly recognizable voices on the planet, deeply engrained in my mind and in the minds of every single person in that room — engrained in practically everyone in the country who was born before or near the middle of the last century.

I don’t remember if it was cold outside, but it was warm in the sanctuary, and golden light poured through the huge arched windows.