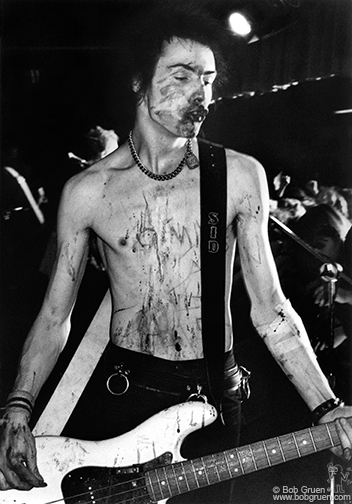

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Sid Vicious had cut himself. That was hardly unusual. He sliced himself all the time. But this wound was seriously deep and ugly, and it was festering.

It was January 1978, and the Sex Pistols were on their headline-grabbing, beer-and-spit-spewing, 12-day tour of America. Riding along on their bus with them was top New York rock photographer Bob Gruen.

Vicious had taken a knife from one of the band’s bodyguards and, apparently skeptical of its sharpness, drawn it across his arm. It turned out that, yes, in fact, it was sharp, very sharp.

He was drinking steadily, which was probably numbing him to the pain from the now two-day-old, bloody gash, along with numbing him to whatever else was going on.

In Atlanta, a hospital had refused to treat the surly English punk rocker, very likely because he was so difficult, Gruen speculates. Since no one else was doing anything about it, the photographer, a former Boy Scout, took it upon himself to clean out the bass player’s wound with some alcohol, then closed it up with some butterfly bandages.

That’s one of Gruen’s defining characteristics: He just does it. In fact, that’s also why he was on the bus in the first place. He had asked Malcolm McLaren, the band’s manager, if he could come along at the last minute, and it turned out there was one seat left.

“Yeah, I jumped on the bus,” Gruen recalled, during a recent interview in his Westbeth studio in the West Village. “Malcolm said, ‘Come along,’ and I did. It was very spur of the moment — like most things in my life. Malcolm said only 12 could come. They were on a bus in a parking lot ready to pull out. I didn’t have a girlfriend at the time, so I didn’t have to come home. … I woke up 10 days later in San Francisco.”

As for his impromptu field surgery on Vicious, Gruen said, “He appreciated it.”

As for the tour itself, it was bedlam.

“Oh yeah, people threw things at them all over the place,” he said. “They tried to encourage a hostile, anarchist atmosphere.”

Gruen’s assessment of the Sex Pistols: “They were just the most obnoxious…. I didn’t know what the fuss was about. They weren’t very good.”

Iconic rock images

In a decades-spanning career, Gruen has photographed everyone and anyone in rock ’n’ roll. Some of his shots are among rock’s most iconic images.

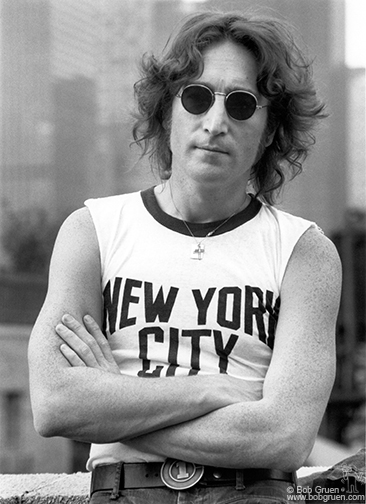

At the other end of the spectrum from the Sex Pistols was John Lennon, Gruen’s friend, who famously advocated for peace and love. It was Gruen who captured the signature shot of the ex-Beatle wearing a sleeveless “New York City” T-shirt, and the one of Lennon flashing a peace sign in front of the Statue of Liberty.

Gruen grew up just outside New York City on Long Island. His father was an immigration lawyer and his mother a real estate lawyer.

“So I grew up knowing how to negotiate,” he quipped. “It’s helpful if you’re trying to get a backstage pass.”

As a youth he started taking photos with his dad’s Minolta. His mom’s hobby was photography, so that helped hone his eye.

However, without going into detail, he said of his family picture, “The whole thing was a situation I left as soon as I could.”

He tried a couple of colleges, but, as he put it, “It didn’t work out.”

So, 1965 found Gruen, at age 18, moving to the Village, sharing a Sullivan St. apartment with friends in a psychedelic folk band, the Holy Modal Rounders.

“They did the vocals for the movie ‘Barbarella.’ That’s their claim to fame,” he noted.

His photos of the band caught the eye of the record label’s publicity department, and that got him started on his way shooting top acts, such as Tommy James and the Shondells (“Crimson and Clover”).

Gruen went on to photograph Ike and Tina Turner, and thoroughly enjoyed working with them. He said that, at the time, he wasn’t aware of Ike’s abusive behavior toward Tina.

Lennon’s personal lensman

He met Lennon while photographing him for an article. They hit it off and he became the personal photographer for John and Yoko.

“When they wanted a picture taken, they would call me,” he said.

For example, Gruen took a very intimate shot at the Dakota of a ponytailed John wearing a white bathrobe holding a newborn Sean as a smiling Yoko looks on. But Gruen said he didn’t want that one published in The Villager because it’s too private.

Regarding the photo of Lennon in front of the Statue of Liberty, it was actually Gruen’s idea. Most of his shots aren’t set up or posed, but this one was. It was October 1974. Lennon was 34, Gruen 29.

“I took it to help John Lennon in his deportation case,” he explained. “He was the kind of guy I thought we should keep here. I didn’t think we should be throwing him out. I thought we were supposed to be welcoming great artists. Nixon thought Lennon had been thinking of leading a protest against the Republican Convention. Lennon was pro-peace and anti-Vietnam. And it was the first time 18-year-olds could vote.”

Ultimately, the defense proved that the U.S. government had unfairly singled out the singer for deportation.

Gruen visited Liberty Island last year, and noticed many people striking the Lennon peace-sign pose in front of Lady Liberty.

“In just the short time we were there, a lot of people were copying that pose,” he noted. “I think a lot of people think of John Lennon like they think of the Statue of Liberty — ‘peace and freedom.’ ”

Story of the NYC T-shirt

As for the T-shirt shot, taken in August 1974, Gruen said there are many inaccurate accounts about it.

“People have embellished the story of it,” he said.

One version has it that Gruen was about to take the shot, but felt it just needed something more — or less — so he ripped the sleeves off right then and there.

“The T-shirts were sold, not in a store, but by a guy on the sidewalk in Times Square,” Gruen explained. “I would buy them, and just cut the sleeves off because I felt it gave it a better New York City look. I used to give them to friends.

“Years later, Lennon was back from his ‘Lost Weekend.’ He had a penthouse apartment in the East 50s — he wasn’t back with Yoko. He was back from L.A., sobering up. I didn’t know if he still had the shirt. It was during a session for an album cover.”

As for why the photo has become one of the best known of Lennon, Gruen said, “I don’t know what it is…. . I just believe in good, powerful graphics. I’m proud to be from New York. I like the energy of the city, and it was just a cool thing to say back then. He’s very accessible [in the photo] — yet he’s still a pop star with the sunglasses.”

Neither of the two Lennon photos was immediately popular when they were taken in the early 1970s, but they became so after Lennon’s death in 1980.

Bonded with ex-Beatle

Gruen both admired Lennon and clicked with him.

“Oh yeah, he was a very cool guy,” he said. “He was very smart, very perceptive, very funny. So he was always fun to hang out with because he was always making jokes. He had a cynical sense of humor — we shared that in common. We could relate.”

What about the flip side of Lennon’s personality, the troubled, fragile side?

“I didn’t really get into psychoanalyzing him,” Gruen stated bluntly. “He was a friend. I didn’t ask him about his mother. You don’t interview your friends.”

However, he did share an anecdote about Lennon, about how the photographer stopped by the Dakota one time and the rock star, as he often did, was watching television.

“He liked to watch TV a lot,” Gruen noted. “He watched everything. I complained that I was trying to talk to him but couldn’t because of the TV. He said, ‘Well, you can talk if the window’s open. This is my window to the world.’

“I’m sure he would have a field day with the Internet,” Gruen reflected. “John would have used it for peace and freedom and being funny.”

The lensman is very proud of his connection to Lennon.

“It gives me a chance to be able to keep talking about peace and freedom,” he said, “which is a good message to have.”

Flying high with Zeppelin

Although he spent far less time with them, Gruen also captured one of the best-known shots of Led Zeppelin, with the band posing in front of their privately chartered Boeing 720, the Starship.

“That’s on the very first roll of film I took of them,” he recalled. “I think we were on the way to Cincinnati or something like that. At the time, I took four or five shots, just a little souvenir for the band — it turned out to be one of the icons of ’70s rock excess. I think Robert Plant asked me to shoot it.”

However, Gruen had little interaction with Led Zeppelin during the actual flight.

“Because I wasn’t a girl, they hardly spoke to me,” he said. “I mean, they were mostly into girls.” Ironically, he noted with a smile, “Nowadays, they talk to me.”

Although he was documenting rock’s lavish lifestyles, he wasn’t necessarily making too much cash himself, a situation that continues to this day, he noted.

“It’s not that lucrative — because people are stealing stuff off the Internet,” he said. “I do sell signed prints through galleries, but I’m not rolling in dough.”

Yet, the positive part of people ripping off his photos from the Internet, he said, is that, “The more people see it, it makes the actual prints more valuable.”

(For this article, Gruen sent high-resolution digital images for the print version, but lower-resolution versions, with his name stamp on them, for online use.)

Now, he said, he’s more into the “history” of rock photography, which is something he can provide through his countless classic prints.

Making the Max’s scene

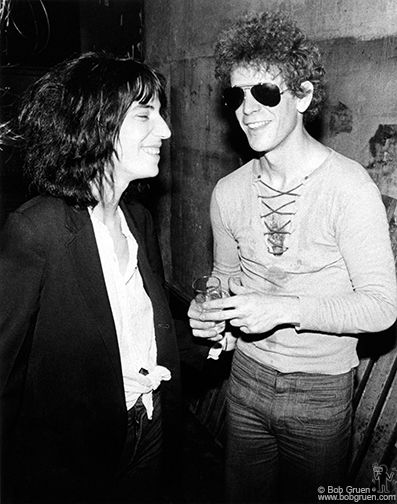

Gruen also spent a lot of time hanging out with the New York Dolls, the genderbending, early punk band, and became part of the Max’s Kansas City scene. He got to know Blondie and Patti Smith.

Unlike others, he never liked watching TV at night, instead preferring to go out to Max’s. It was just what he would do in the evenings.

“I enjoy going out to clubs. I enjoy seeing bands play,” he said. “I enjoy meeting people. And I turned out to be not well-suited to working a 9-to-5 job. Luckily, I was a good photographer.”

After the Sex Pistols’ U.S. tour, he went to England, with McLaren’s phone number being his only contact there. He covered the Sex Pistols again, but also The Clash, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Elvis Costello and Billy Idol, among others.

“My life has always been ‘one thing leads to another,’ ” he said. “You wake up in the morning, the phone rings, and you make the best of it.”

Changes in photography

Things have changed so much in photography, first with the advent of autofocus in 1990 and later digital photography, and then the explosion of the Internet. He’s been shooting digitally since 2000.

But Gruen, 68, is not one to bemoan change. Nor does he romanticize the past over the present.

“There was so much going on,” he said of rock photography’s heyday. “Now, with the Internet, there seems to be more, but there’s less, because everyone’s home with the Internet with their little window. You used to take a photo at a concert. It was published two weeks later in a magazine, and that was news. Now, before the band has finished their first song, you can send a photo. I can’t compete, and don’t want to compete, with that kind of speed.

“It used to be a lot harder work. You used to have to carry a lot of heavy equipment. When I started, I had to carry flashbulbs.”

He quipped, “Today, people use Instagram to mess up the picture. We just used alcohol and drugs. …

“But you can’t go back,” he said. “You don’t get milk delivered in a bottle by a guy in a wagon pulled by a horse. I’d rather be riding a horse, but… . I’m just happy to be here.”

Changes in the Village

“Here,” as in Westbeth, “used to be west of nowhere,” Gruen noted. The neighborhood has changed radically since 1970 when he moved in as one of the artists housing complex’s original tenants.

“Nobody knew where Washington St. was,” he recalled. “When you got past Eighth Ave., it was like no-man’s land — abandoned factories and piers. In the ’80s, AIDS killed off the kind of hedonistic sex with strangers. In the ’90s they cleaned up the whole neighborhood. They took down the highway, built the park,” he said, referring to the formerly elevated West Side Highway and the new Hudson River Park.

“I always wanted to live in a nice neighborhood,” he deadpanned. “Now we live in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in New York. But we’re surrounded by tourists, and the high rents have forced out the mom-and-pop shops.”

Flipping out at Superior Ink

Gruen isn’t too happy about the new Superior Ink building, one of whose empty penthouses looms darkly directly across the street from his studio window, blocking his north view.

“You can see the pipes and wires hanging from the ceiling — no one’s ever lived there,” he said. “They paid $25 million for it, then resold it for $34 million.”

In fact, that’s exactly the idea, he said: No one will ever live there, and the place’s owners will keep flipping it as an investment.

“These people have other apartments,” he said. “They should have parked their money in the bank instead of that penthouse.” On the other hand, he added, “It’s better than the crack addicts” that used to hang around the area.

The more things change…

Just as photography and the Village have changed, so, too, has the music scene. While Gruen said CBGB was a good venue for its time, he doesn’t put it above what’s happening today.

“Right now, there are dozens of clubs in Brooklyn where young people in their 20s are having a good time,” he said. “They’re doing it their own way. It’s spread out over the world now with the Internet.”

As for bands that he documented that never made it, Gruen mentioned the Steel Tips and the Miamis.

“Everybody loved the Miamis,” he said. “They wrote like 70 No. 1 hits that were never recorded.”

Nowadays, he likes the Sex Slaves and Barb Wire Dolls. He’s also a big fan of Billie Joe Armstrong and Green Day. At Gruen’s recent 68th birthday party, Armstrong gave him a skateboard with a graffiti-style painting of Joey Ramone on it, which the photographer hung up prominently in his studio.

In his personal life, Gruen is married to Elizabeth Gregory, a fashion designer and artist, who is also currently helping him archive his work. Gruen has a son and a daughter and four granddaughters.

“They’re actually the biggest joy in my life, which was a surprise for an old punk rocker,” he said of his grandkids. “I enjoy visiting them.”