BY GERARD FLYNN | In March 2006, Ramy Isaac “self-certified” that construction plans for a sixth floor and penthouse addition to a five-story walk-up in the East Village were lawful. That year was a good one for developers — 48 percent of new construction applications to the Department of Buildings were self-certified.

Under professional certification, as it’s called in the business, architects and engineers are allowed to confirm that their plans comply with applicable laws and start work, without prior Buildings inspection.

The program, which was increased under the Giuliani administration in 1995, can have serious side effects, however, for tenants — as rent-stabilized residents at 515 E. Fifth St. began to find out not long after the Buildings Department approved Isaac’s permit application.

At the time, he was employed by Magnum Management — owned by notoriously aggressive East Village developer Benjamin Shaoul, who reportedly purchased the walk-up for just under $3 million in late 2005.

Permit in hand, Shaoul et al. proceeded to renovate emptied apartments and erect the additional floors, thus turning the late 19th-century tenement into a dusty and noisy hell, rent-stabilized residents said.

By mid-April 2006, the trail of violations against Shaoul by the Department of Buildings for work at the site was just beginning.

Forming a tenants association, residents took their growing complaints to tenant advocacy groups and local Councilmember Rosie Mendez. Eventually, Borough President Scott Stringer got involved, demanding the Buildings Department revoke the permit for the rooftop additions.

By the end of 2006, Shaoul had started renting out the nearly completed apartments. Yet, Buildings had ordered him to “discontinue illegal use” because he hadn’t obtained a required certificate of occupancy.

Claiming the enlargements violated the zoning resolution, specifically, the “Sliver Law,” which caps height in certain areas of the city, tenants took their case to Buildings. But the agency found Shaoul was in compliance.

In 2007, the tenants contested D.O.B.’s decision at the Board of Standards and Appeals. Surprisingly, the B.S.A. ruled for the tenants.

The B.S.A. reversed D.O.B.’s ruling and ordered the enlargements taken down.

Shaoul and his burly legal eagle, Marvin Mitzner, appealed the B.S.A. decision in New York State Supreme Court. They lost, then lost again at the state’s Appellate Division.

For the tenants, it was a kind of Pyrrhic victory: The illegal rooftop enlargements stayed up, and the rent from them — an estimated $12,000 a month — kept rolling in.

Tenants claimed the penthouse addition violated a 1929 state statute, the Multiple Dwelling Law, specifically, violating fire and other safety requirements; and that, at more than six floors, the Old Law tenement — once home to New York’s poorest immigrants — was required to have an elevator.

The Buildings Department disagreed, saying that, among other things, Shaoul’s proposed additional fire safety measures, such as installing sprinklers throughout the building, were “deemed equivalent to the fireproofing measures laid out in the Multiple Dwelling Law.”

But in October 2008, the B.S.A. again shot down D.O.B.’s decision. The agency exceeded its legal jurisdiction in waiving the Multiple Dwelling Law requirements, the B.S.A. said.

The tenants’ attorney, Harvey Epstein, of the Urban Justice Center, told The Villager at the time that he thought the next step should be an order to demolish the illegal added stories.

Buildings has declined to answer how Shaoul can rent the property without a certificate of occupancy.

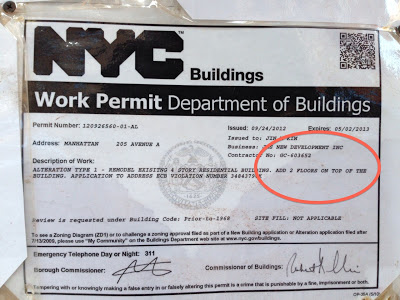

Yet, in August 2012, Shaoul applied to the B.S.A. to have part of the enlargement — the sixth floor — “vested,” in accordance with the prior zoning from before the 2008 East Village / Lower East Side rezoning, which downzoned the block the building is on.

The building permit for the rooftop addition lapsed in 2008. Shaoul sought its reinstatement and claimed that “common-law vested rights,” which allow developers to complete construction started before a zoning change, may be applied.

However, because D.O.B. deems the permit unlawful, the B.S.A. denied Shaoul’s application in September 2012.

But no order from Buildings to dismantle the enlargements is likely just yet, and Shaoul has decided to sue the B.S.A. again — pursuing another variance based on the prior zoning.

Andrew Berman, executive director Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, which has worked closely with the tenants, called Buildings’ lax response “incredibly frustrating.”

“The city seems very good about doing enforcement when it wants to,” Berman noted. “But in cases like this, landlords and developers just seem to get away with it for year after year after year.”