A heroin user nodded out on Union Square West last year amid fliers promoting an Occupy Wall Street “wildcat march” on May Day that had rained down from a nearby rooftop.

BY LAEL HINES AND LINCOLN ANDERSON | Community Board 5 has given its conditional approval for a needle-exchange program for heroin users to operate just steps away from Union Square Park.

On July 11, the full board of C.B. 5 O.K.’d the application of the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center to the State Department of Health to allow the center to distribute clean needles to heroin users right outside the park, which is notorious as a locus for heroin users.

According to the C.B. 5 resolution, the board received support from local businesses for the program.

The needle exchange would operate five days a week, three hours per day, starting some days as early as 11 a.m., and on other days going as late as 8 p.m. or 11 p.m.

A stipulation in the C.B. 5 resolution states that the exchanges must be done discretely:

“LESHRC will identify safe and discrete places to do syringe exchange and will not do exchange in front of residential buildings, nor will they ever use tables.”

On July 8, three representatives of the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center presented the application to a meeting of C.B. 5’s Education, Housing and Human Services Committee.

The three representatives wore T-shirts with slogans for one of the center’s programs, rapid hepatitis C testing: “Tested: Yes,” one shirt said on the front, with “Status: Crusty” plastered on the back. The two other members’ T-shirts referred to other populations the programs also serves, “drug users” and “queers.”

“Crusties,” or “crusty punks,” are a subset of young homeless people, also sometimes known as “travelers,” who have a reputation for substance-abuse issues, including notably, heroin.

The center, a nonprofit charitable organization, aims to limit the spread of H.I.V. through clean syringe exchange and the donation of hygienic materials. It additionally provides overdose prevention kits.

According to the New York State Department’s AIDS Institute, syringe-exchange programs in New York are associated with and may be responsible for at least a 50 percent and possibly up to a 75 percent decline in the rates of new H.I.V. infection.

Sadat Iqbal, the group’s director of outreach and community development, told the committee meeting, “Not only do we provide lifesaving materials in the short term, but we also connect those addicted individuals to the care they need. We’re trying to reach out to these individuals in order to educate them about H.I.V. risks, while also bringing them down to our Downtown center, where they can access help and counseling for the long term, which will ultimately improve their quality of life and relationship to the public.”

Alexandra Dryer, the executive director and C.E.O. of Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, further described the positive impact of their outreach.

“Originally, it was that one in every two injected drug users was infected with H.I.V. or AIDS,” she said. “Now it’s down to 3 to 8 percent. The amount of money it costs in public health — if you look at the cost of a syringe, even if you add the overhead of staff, etc. — the syringe itself could be a dollar, whereas treatment for either hepatitis C, H.I.V. or AIDS is upward of half a million dollars. The public health impact and the impact on the person are tremendous. This is really a mechanism that allows us to eliminate those costs in addition to ameliorating the quality of life of the individual.”

The Parks Department prohibits syringe exchange within its parks. As a result, addicted individuals around Union Square Park currently must walk a few blocks away, to a location at Second Ave. and 14th St. to receive clean syringes. Under the proposed plan, clean syringes still would not be permitted to be distributed right in Union Square Park or in the Department of Transportation pedestrian plaza on Broadway between 17th and 18th Sts.

According to the Harm Reduction officials, there has recently been an increase in “substance users,” as they call them, in the Union Square area. Iqbal said this is largely due to displacement of the users from Tompkins Square Park and the East Village due to factors including police sweeps and gentrification.

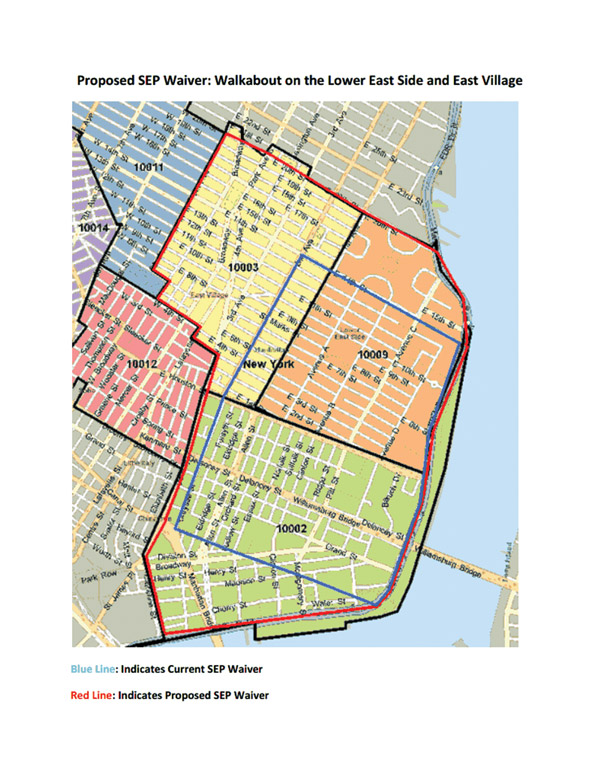

To address this uptick, the Harm Reduction Center is requesting a waiver from the AIDS Institute to allow it to expand the area in which it can distribute and collect needles. Currently, this zone’s northern boundary is 14th St. and its western boundary is Second Ave., and the zone then extends over to the F.D.R. Drive and Downtown, covering the Lower East Side. So, for users in Union Square to get clean needles, they have to walk at least as far as Second Ave. and 14th St. Of course, they can also get needles at the center’s offices, down at 25 Allen St.

The needle-exchange program is now seeking to extend the waiver zone’s western boundary to Fifth Ave. and the northern boundary to 20th St.

However, at the committee meeting, this idea was largely met with opposition by Union Square area residents.

Among them were a Mr. Saltzman of the Victoria co-op owners’ organization, representing the 21-story, 494-unit, white-brick building at 7 E. 14th St..

“I’m concerned about my 12-year-old and two 8-year-olds that are walking around, because this is their neighborhood,” he protested. “What happens if the person [set to receive clean needles] somehow becomes belligerent or argumentative? What happens in the worst-case scenario?

“If there are other syringe-exchange programs that have been approved to be in this neighborhood, and we’ve seen such a vast reduction in AIDS and hepatitis results, why are you necessary?” Saltzman said. “Your success has caused you to not be necessary.”

Sherry Levy, another Union Square resident, warned that junkies would be dispersed through the neighborhood rather than kept concentrated, as they largely are now, in a corner of the park.

“You’re going to help get them out of that area and scatter them around the commercial districts so that they can participate in the needle exchange,” Levy objected. “I walk these streets all the time and I don’t see dirty needles around. That does not seem to be our problem.

“Our problem seems to be our poor, drug-addicted people that are gathered in that certain area of the park,” she said. “At least we know where not to walk. Once we take them out of that area, we scatter them. We are granting them access to areas that they weren’t in before.”

A Dr. Gerson, a Union Square resident and doctor, was disappointed by what he had not heard at the meeting.

“I’ve treated IV heroin users for 12 years,” he said. “My problem is I heard very little about what you do to get people into treatment. Because just giving them needles is basically encouraging their drug use, saying it’s perfectly fine — and it’s not perfectly fine.”

One local resident who only gave his name as Steven said, “I understand how it may attract people to a neighborhood that might threaten other people in that neighborhood — drug dealers or drug addicts, you might bring an element into this neighborhood that they may not like. It’s the ‘Not in My Backyard’ [NIMBY] syndrome.”

Nevertheless, some Union Square residents showed strong support for allowing syringe exchange in their neighborhood.

“Do you have any idea how much that would cut down on the spread of H.I.V.?” said Claudia Smith. “If you’re an addict, you’re an addict. It’s not like it’s going to stop. They are making it less unhealthy,” she said of the Harm Reduction Center.

“Drugs are already in ‘their own backyard,’” she said. “You can see it here in the park. At least now, it’s healthy and not as dangerous. I think it’s all positive.”

The result was that the committee adopted a resolution phrased as “recommends denial unless” — meaning that board members asked for certain stipulations to be met, in return for which, they would recommend approval. This was also the way the full board’s resolution was phrased.

The Harm Reduction Center will be required to respond to the community concerns expressed at the meeting. This will include the organization’s adjusting its hours to best connect with its clients and, again, to refrain from performing syringe exchanges in front of Union Square residents.

Gail Fox, a Union Square activist, said more outreach is needed by the Harm Reduction Center — not to the addicts, but to the residents, to assure them about the program.

“I’d like to see them do significantly more substantive, community outreach before they are further vetted,” Fox said. “They should have more follow-up and face-to-face contact with all the residents — and their elected representatives — in this area, as well as the businesses.”

After receiving C.B. 5’s conditional approval, the needle exchange has applied to the state for the East Side waiver.

Iqbal told The Villager the Harm Reduction Center also will be seeking an expansion of its waiver so that it can distribute clean needles in more areas on the Lower West Side, specifically, around the Christopher St. corridor. This effort wouldn’t be targeting heroin users, he said, but transgender individuals who use needles for their “hormone therapy.” The center will be coming to Community Board 2 in a couple of months to request approval for this waiver application, he said.

Actually, Iqbal described this as more of an “update” to their waiver, since the Harm Reduction Center currently can distribute needles in a part of the Meatpacking District. However, the population they hope to serve is no longer there.

“Back in the ’80s and ’90s it was known as ‘The Stroll,’ ” he said. “Today it’s the Apple Store and Diane von Furstenberg.”