BY JERRY TALLMER | Near the end of Neil Barsky’s “Koch,” the hugely enjoyable 95-minute docu-bio that, as if by arrangement with God — or maybe Satan — opened in New York City on the very day of its 88-year-old subject’s unwilling 2 a.m. departure from this earth, we glimpse an adoring fan of the triple-term former mayor clutching at him while begging: “You must run again!”

“No,” the Koch who would have relished a fourth (and fifth and sixth) term tartly responds. “You threw me out, and now you must be punished.”

And you know what? He half believes it. We know this because just a bit earlier we have heard this proud Jew say, tongue only slightly in cheek: “I believe in the afterlife, in rewards and punishments — and I expect to be rewarded.”

One of those rewards is not to be buried in a small, old, hidden-away cemetery like the five tiny Greenwich Village graveyards that longstanding Greenwich Villager Koch inspects and rejects in between hospitalizations.

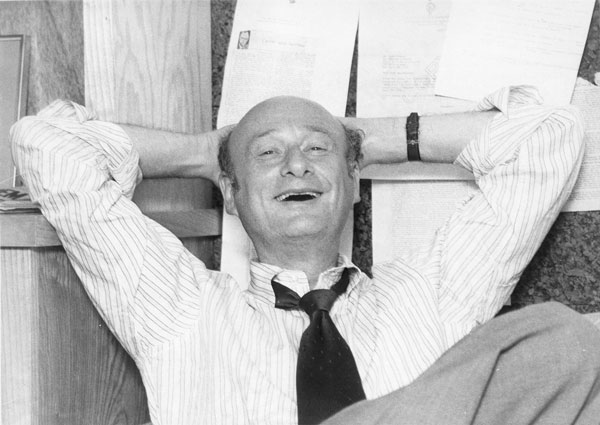

Speaking of cheek: The close-in cameras of director of photography Tom Hurwitz have brought out the apple cheeks and owl’s nose that unkindly turn the aging Ed Koch into a Mr. Punch; whereas at least one family photo of tall young Ed in his — I’m guessing — twenties, shows him to have been quite a handsome young buck.

When I first met him, circa 1960, he was already a tall, funny-looking, balding, political galoot, but not yet a Mr. Punch.

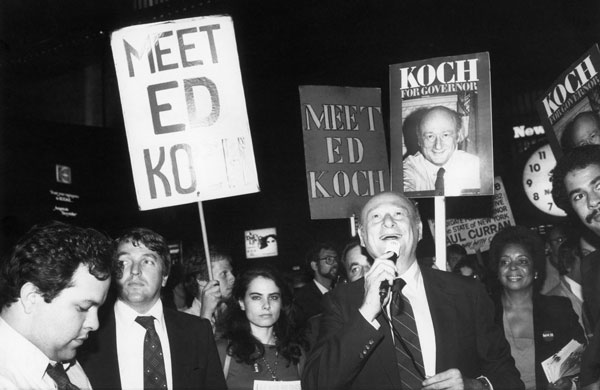

Speaking of the Deity: At the top of the film we hear Ed Koch (mayor, 1978-1989) surveying this unmanageable city — blackouts, looters, transit strikes, crumbled housing, no housing, traffic jams, labor relations, race relations, strikes, Son of Sam murders, municipal bankruptcy (“We were now beggars”), FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD, the whole megillah — “and it belongs to me!” Ed Koch exults. “Thank you, God.”

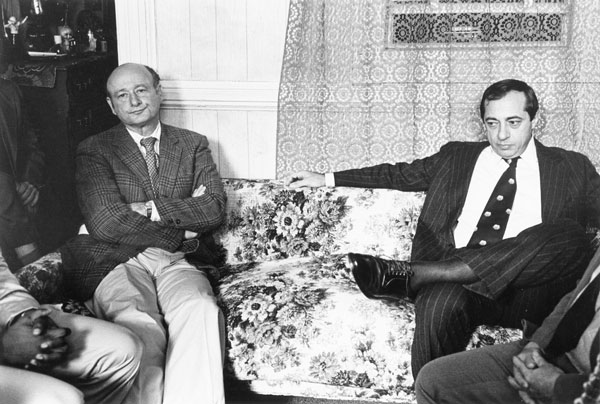

The Saturday afternoon crowd at the Lincoln Plaza, where I saw Mr. Barsky’s “Koch” (it’s also at the Angelika), roared and laughed at that line and everything else. At least half the audience was comprised of young men and women — or men and men — who had not yet been born, or just barely been born, when Ed Koch first ran for mayor (against Mario Cuomo) in 1977.

Ed Koch? Good and bad were all tangled together in this most complex, most contradictory of politicos. Every documentary has its share of talking heads, and “Koch” the movie has its full measure of City Hall aides and authorities and journalists pivoted around Joyce Purnick, former New York Post reporter, former New York Times “Metro Matters” columnist, who keeps Koch Plus and Minus matters in useful perspective.

No, Ed Koch did not suffer fools gladly. He was indeed very tough on them — “Calls them as he sees them,” says one intimate, “but he also knows a wacko when he sees one.”

Film editor Juliet Weber has assembled “Koch” as a mosaic, a kaleidoscope of hundreds of interlocked, interrelated pieces, large and small, like a cathedral’s stained-glass window. This may bother some viewers who would prefer a straightforward chronological sequence, but it didn’t and doesn’t bother me; life doesn’t run in straight lines, nor do the lives of great cities.

It’s a bad pun, but Ed Koch’s personal life didn’t run in a straight line either. “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo” was the slogan that was plastered all over Queens in 1977 and ’78 — maybe by hired hands of Andrew Cuomo, son of Mario Cuomo, maybe not. It made no difference.

“A primary is like a civil war,” Hizzoner says, “but when it’s over, it’s over.”

The question of lifelong unmarried Edward I. Koch’s sexual orientation will never be — how to put it? — laid to rest, and it is hard for me not to agree with the ex-mayor’s angry denunciation of some future official Orwellian form that demands an answer on the dotted line to “Are you gay?” or “Are you straight?”

“I’m not going to do it,” we hear Koch stubbornly proclaim, followed by: “It’s none of your f—— business.”

Nor is it.

What follows, filmically and logically, is Larry Kramer exploding in rage against the mayor, who was burying himself ever deeper in the closet while, starting in the early 1980s, the black death of AIDS was wiping out playwright Kramer’s friends and other good people by the hundreds and ultimately the thousands.

On other hot-potato social questions — abortion, for instance — Koch was neither naive nor silent. His mother, he tells us, or tells former New York Daily News and Wall Street Journal reporter Neil Barsky, had long ago revealed to her son how she’d once almost died from an illegal abortion.

When I heard Koch saying this, I had a hot flashback of my own. It was Koch strategist David Garth who’d thought up recruiting Bronx-born Bess Myerson, the first Jewish Miss America, as Koch’s “beard” — the true beauty who, in the year of “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo,” would go everywhere with Koch, every day, every night, every opening, every ribbon-cutting, every everything, to demonstrate his non-homosexuality.

Well, I once interviewed Bess Myerson, after Koch made her commissioner of Cultural Affairs. We had never met before in our lives, mind you, would never meet again. She kept the interview going for two hours, and she suddenly started telling me, in fulsome detail, about her abortion. Told me everything except the name of the impregnator, which was not Ed Koch.

Yes, Koch “had an insatiable hunger for the camera” — what politician does not? — but he also had guts, and in Freedom Summer, 1964, the summer of the murder of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, long before he was mayor, Ed Koch was marching in Mississippi to establish his credentials.

And yes, he can’t stop talking. Passing through the gentrified (ugh) 42nd Street, he can’t resist saying, out of nowhere, for no reason: “I’ve never been to a Red Lobster.”

Fiorello LaGuardia used to say: “When I make a mistake, it’s a beaut.” Ed Koch could say the same, many times over, notably in the closing of under-used Sydenham Hospital in Harlem, which opened the door to charges of this mayor’s racism.

“Maybe I should have given in to racial terror,” he says cynically, on camera, backed up by how he’d incurred “a great deal of ill will and resentment just because I was white.”

“He’s worse than a racist,” says one critic. “He’s an opportunist.” “It’s all theatrics,” says another.

Koch himself puts it another way: “Some people talk about bringing people together. Other people” — i.e. me, I, Ed Koch — “do it.”

In his time, Koch suffered and survived a heart attack, a bypass, a couple of strokes, paralysis of the face (“That scared the hell out of me”), and periods of depression.

About 10 minutes before the end of the movie we see old, old Ed Koch, all alone, his back to us, trudging down a long, dark, narrow corridor to obscurity. If I were director Barsky or editor Weber I would have made that the closing shot.

Koch the movie does run a bit long. But so did Ed Koch, the man. I’m glad for all 95 minutes of this gripping, anatomical recapitulation of a New Yorker whose likes we’ll not be seeing again soon.