Vuillard’s recapture of things past, in living color

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

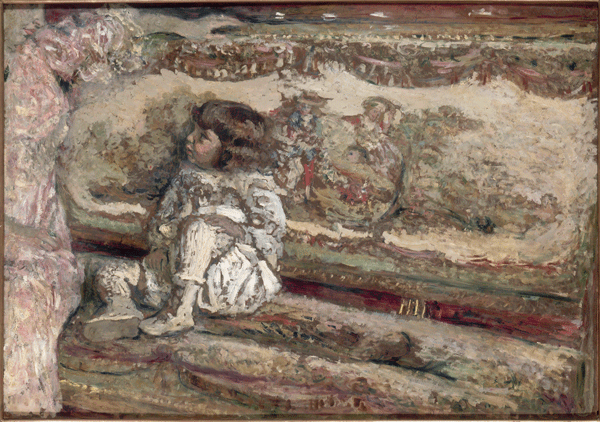

He is sitting, this child, hands locked under one scrunched-up knee, near one end of an elaborately brocaded and landscaped couch that is much too large for him — a little lost pea in a yawning peapod — the whole effect, as so often with master colorist and humanist Vuillard, being that of complex chamber music: here a wintry minuet in grays and ivory whites and earthy greens.

The little boy’s head is cocked to his right (our left) as if straining to overhear something being said to him or above him by one or more adults whom we do not see. The name of this child, a wall label tells us, is Claude Bernheim de Villers — and everything about this 1905-06 snapshot (oil on paper, mounted on plywood), taken when Claude was three, bespeaks money, privilege, protection, comfort. He might be a figure out of Proust when he grows up, and so might much else in this seductive assemblage of times past and times lost.

The word “snapshot” in the previous paragraph is used advisedly. Long ago — that is to say, four or five decades before the invention of the camera phone — I got used to ignoring the tiny zip-zip-zippp of my photographer friend Saul Leiter’s equally tiny Leica as he clicked away, unnoticed by all of us, at the whole environment, the whole scene, indoors, outdoors, wherever, with results that were sometimes, when printed up, shockingly beautiful and always surprising.

That is the kind of “snapshot” Edouard Vuillard took throughout his lifetime (1868-1940), in and out of Paris. But the camera was in his head, in his eyes.

He didn’t do much landscape painting, except when the subject — the human subject — was somewhere in a landscape, as with Lucy Hessel, at the seashore (1904), or Lucy in a meadow in Normandy (1905). But most of what we see of Lucy, Misia, and all the others, is at what might be called “real life” — safely indoors (though sometimes at odd disposition of their heads, torsos, arms, legs — just as if caught, unposed, by camera).

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

They would have to be indoors to give Vuillard the domestic background (kitchens, dining rooms, living rooms) he recapitulated in oil paint as few other artists before or since. Well, maybe Bonnard, his contemporary — or, in a quite different way, Van Gogh.

Busy-busy bourgeois wallpaper? Where most wielders of the paintbrush would blank it out, Vuillard defiantly kept it in, played against it, threw one crazy patterned excess against another crazy excess — and then some.

For just one of dozens of instances, take his “Misia and Vallotton [her husband] at Villeneuve, 1899.” She with her rust-colored hair right foreground, a bright yellow scarf atop her brown and black checkerboard housecoat, Vallotton standing behind her, facing away from her (and us), in a royal blue suit of some sort, one hand clutching opposite elbow; all this backed by a patterned floral wallpaper in white and orange and offset by a small table vase of red blossoms. Misia is turned away to — I’m guessing — her mirror, which is out of the frame

to our right.

Adjacent to all this, a quieter painting of Misia herself, just head and shoulders and that pile of rusty hair, pink-cheeked complexion, thoughtful, grave — a dark blue flower at her shoulder, a cocked eyebrow fighting, maybe, not to fall asleep in her stiff-backed wooden chair. The background? Surprise, just a patch of solid mustard-colored wall.

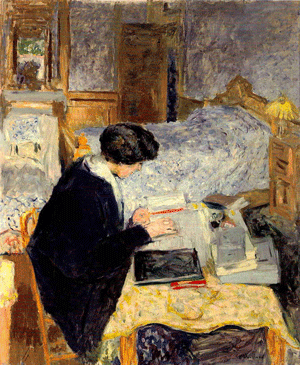

You don’t need wallpaper to admire — half fall in love with — various other Vuillard women. Mme. Marcel Kapferer, for instance, just sitting, listening to someone off camera, all dolled up in a glorious pink and gold striped flowing silk dress, an open book resting at her elbow, her left hand propped against her chin, her left forearm bearing an incongruous modern touch, the black strap of a wristwatch. I had always thought wristwatches came in from the trenches of World War I. This portrait of Mme. Kapferer is dated 1910.

Or, in a painting that begs to be Whistler-titled “Arrangement in Blue, Black, Yellows and Green,” but is instead only brought to us as “Marcelle Aron (Mme. Tristan Bernard),” we discover this black-clad, pearl-necklaced, turbaned, concerned Parisienne conversing with us from what may be the same elaborate couch on which we first encountered three-year-old Claude Bernheim.

There are at least four degrees of yellow, some of them playing tricks on us from a large background mirror in this big, evocative work, but I like it for a closer-to-home reason: the long, sensitive face of Mme. Tristan Bernard is not unlike the face — one of the faces — of Frances, who is my wife.

Don’t think that Vuillard only did portraits of females, including of course the artist’s mother, with whom he lived all the years until her demise. Quite to the contrary. His paintings of men, including the husbands of those two muses, sometimes convey almost as much information as a good novel.

Even a quick sketch, such as Vuillard’s high-tension pastel of American art dealer Sam Salz sitting, hands clasped, conveys all the nervous energy of the Hollywood where Salz was a sometime shooting star.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

One of these same Kapferer brothers — Marcel, the one reaching for whatever pages of newspaper his brother is not reading — will some years and life accomplishments later, in the 1920s, sit for an oil painting by Vuillard that’s as meticulous and prestigious as anything by John Singer Sargent.

Speak of the past recaptured. And, nowadays, distorted. I can’t help thinking that this high-collared Eminent Personage in his stiff-backed wooden chair is how that inflated clown Romney likes to think of himself — but oh my, what a difference.

When the Jewish Museum announced this show, some months back, one’s first thought was: What do you know, Vuillard was Jewish!

Turns out he wasn’t, of course. He merely hung out with Jews, thought like Jews, was their ally in the arts…and bedded at least two of them.

Says Stephen Brown, the excellent curator of this excellent occasion:

“The mission of the Jewish Museum is not solely to show Jewish art. It is also to represent and interpret the Jewish experience. Here, to show how Jews have been influential in the world of culture.

“The people Vuillard lived with became his subjects. The three brothers Natanson [one of them Misia’s husband] came from Brussels to Paris in 1891, bringing with them La Revue Blanche. It was like a little avant-garde group of today, all living together until the money ran out, with the poet Mallarme at its center.

“In 1912, Lucy’s husband, who managed the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery [Vuillard’s home base], broke away, founded his own gallery, and took Vuillard with him. The Bernheims never forgave this.”

Well, maybe not. There are worse things not to forgive, a past not to recapture. Remember that little three-year-old boy in silk pajamas on that big embroidered couch? The son of art dealer and gallery owner Gaston Bernheim — who donated this portrait to the Musee d’Orsay — he was Claude Bernheim de Villers, born September 15, 1902 in Ile-de-France, dead sometime in 1943 at Oswiecim, Poland — also known as Auschwitz.